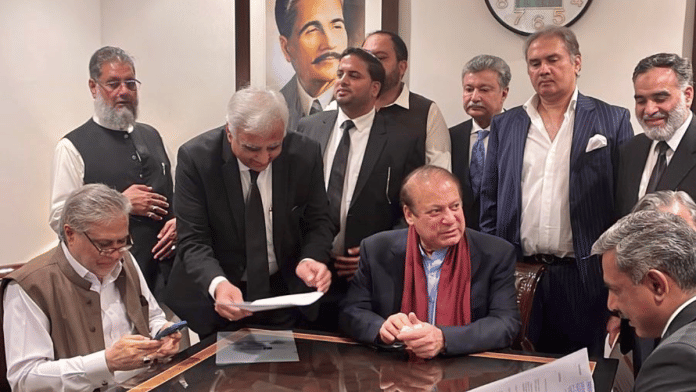

The 73-year-old former three-time Prime Minister of Pakistan, Nawaz Sharif, is back in his country after four years of self-imposed exile in London. Whether he bails Pakistan out of its economic woes or marches to the army’s band as a ‘prodigal son’ depends on how the dynamics of politics play out in Islamabad. Either way, he will be part of the larger plans of the Pakistan Army, which has been running the show from behind the scenes. The army’s stranglehold and vendetta politics are the last thing an economically woe-begotten country needs at a time when its Western neighbourhood is in a state of flux.

Pakistan’s problems won’t necessarily end with the return of Nawaz, who was compelled to leave the country after being convicted in a slew of high-profile corruption cases. In a country where another former Prime Minister, Imran Khan, is incarcerated over corruption charges, the merits and demerits of Nawaz’s case are of little significance. The army’s support for ‘Mian Sahib’ is evident in a recent statement by his daughter and Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N) leader Maryam Nawaz, where she said that “Imran Khan tried his best to make the Pakistan Army surrender to his will…but his attempt backfired, and now he is facing the music.”

China and the Pakistan Army are now inseparable parts of Islamabad’s past, present and future. When Imran’s Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) criticised the VVIP treatment meted out to “a convict”, Maryam took a swipe at his party, saying that “it will fit in a Qingqi rickshaw”, a popular Pakistani three-wheeler originally manufactured by a Chinese company. Qingqi rickshaws are a small portion of the trillions of favours that Beijing has extended to Pakistan in order to cater to its geopolitical interests in the region. China-Pakistan economic and military cooperation began as early as the 1960s, with the signing of the Sino-Pakistani Agreement in 1963, thus laying the base for another ‘great game’ in the region.

China – Pakistan’s ‘all-weather ally’

Pakistan conducted a training launch of the Ghauri Weapon System on 24 October, which was aimed at testing the operational and technical readiness of the Army Strategic Forces Command (ASFC). China supplied the missile-applicable systems to strengthen Pakistan’s ballistic missile and military modernisation programmes. The US had earlier imposed sanctions on the three Chinese entities that had supplied these items to Pakistan.

China has been providing loans for infrastructure projects to create its own area of influence in the South Asian region and other continents. Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the brainchild of President Xi Jinping that is touted as the “project of the century”, is now intertwined with the country’s rise. No other international connectivity plan, other than the United States’ 1948 Marshall Plan, has been discussed as much as the BRI. Unlike the Marshall Plan, which was introduced after World War II and was purely an economic and infrastructure plan, the BRI is a carefully calibrated strategic agenda to usurp the geopolitical and geoeconomic influence of the West, particularly the US. With China emerging as the largest global lender, economic aid and debt traps could become the most effective tools in the hands of Beijing.

Pakistan is a textbook case of Chinese control over countries that are willing to barter their sovereignty and autonomy for pittance. Pakistan owes nearly $27 billion in commercial loans to China, most of it for the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). China has funnelled $25.4 billion in direct investments into CPEC, a flagship project of BRI. Pakistan’s debt to China is almost twice the amount it owes to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which is one of the largest lenders to India’s economically bankrupt neighbour.

Also read:

Does China need Pakistan?

China needs Pakistan for several reasons, the most important ones being security and strategy. Of all the BRI projects, the one that Beijing values the most is the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). It links China-occupied Tibet, Pakistan-occupied Kashmir and the troubled Balochistan region to facilitate the creation of a trading port for China in the Indian Ocean at Gwadar. The 3000-odd-kilometre infrastructure project is a time and money saver for Beijing in its energy security and trade endeavours with the Middle East and Africa.

But things are probably changing for China and the world. Besides its own economic troubles, Beijing should consider two more factors before investing further in CPEC. What began as a $46 billion project in 2015 grew to about $70 billion in just a few years. But as of today, both China and Pakistan appear to be sceptical about the success of CPEC. New investments under BRI seem to have gone down significantly with the slowing down of the Chinese economy and Pakistan’s debt crisis.

This could lead to a situation where Beijing can seriously consider revisiting the CPEC and putting it on the back burner for some time. Pakistan’s Finance and Revenue minister, Ishaq Dar, blamed the PTI government for failing to secure the Main Line-1 (ML-1) project with China, due to which, he claimed, project costs almost doubled. Minister for Privatisation Fawad Hasan has lamented that Pakistan has failed to realise even one-fifth of the CPEC potential. The country’s biggest failure, he said, is its inability to increase exports, which are required to finance debt and investment-related obligations. Meanwhile, China ‘bashed’ the Pakistan Army for not being able to protect Chinese nationals working on the CPEC project, for delaying assistance to projects, corruption and civil unrest.

It is in the best interest of Pakistan Army to keep borrowing from China in the name of CPEC to keep its nest feathered. For this, it needs the façade of a civilian prime minister, aka Nawaz. It is up to Beijing to buy the army’s story and keep the debt mounting. Going by China’s economic slowdown, it is doubtful that it would sink more money over a failed project.

Seshadri Chari is the former editor of ‘Organiser’. He tweets @seshadrichari. Views are personal.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)