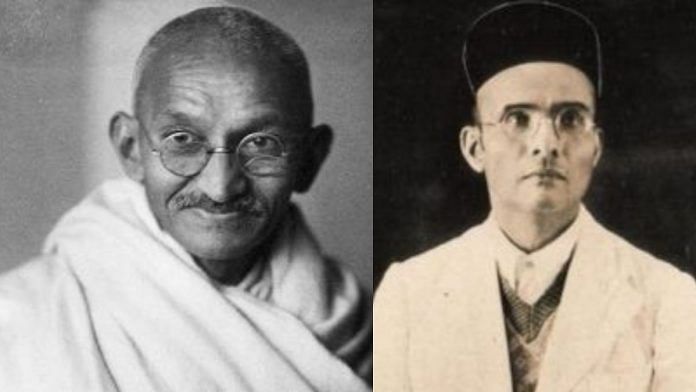

Did M.K. Gandhi enable mercy petitions on behalf of V.D. Savarkar to the British empire? Over the last week or more, this question has animated the political conversation in India. Historians have pitched in on both sides of the ‘yes’ and ‘no’ divide of this question and no less than the country’s defence minister, Rajnath Singh, has weighed in.

At the outset and as a fully paid-up academic historian, I should say that this is not a debate that professional historians can referee. This is not due to lack of evidence that could ‘settle’ the question one way or another. Even in the current cultural climate that has seen a surge in popular and public history, the historian as judge-referee is doomed to fail because Savarkar-Gandhi distinction is not an arcane academic dispute.

The Savarkar-Gandhi relationship is one that concerns every Indian. Both Gandhi and Savarkar define and even divide the political and psychic life of India. Every Indian has a view on Gandhi – regarded as the father of the nation and the figure whose laughing face adorns the Indian currency. Love him or loathe him, the Mahatma is inescapable.

Also read: The real story is Gandhi, Savarkar were on same page on Hindi, Hindu, Hindustan — and caste

Gandhi-Savarkar: A silent division

Tellingly, the two men rarely met each other. Gandhi’s monumental, if brief, political manifesto Hind Swaraj was written in feverish pitch soon after their first meeting in London in 1909. It is often speculated that Savarkar or a figure who held views akin to his was the un-named ‘critic’ to whom Gandhi’s dialogue is openly addressed.

Their political lives and indeed India’s political future changed dramatically soon after their first meeting. Savarkar’s account of the Indian Mutiny was also published and immediately banned in the same year, and he was arrested for his revolutionary activities that espoused violence and sent to the harsh penal colony of Andaman Islands.

A study in contrasts, Gandhi returned to India in 1915 and became the nonviolent face of India’s struggle for freedom. In 1921 Gandhi became the undisputed leader of India after the Non-Cooperation mobilisations. Savarkar was moved on by the British empire from the Andamans to a spell of restricted imprisonment in Ratnagiri in the same year. Whereas Gandhi’s politics extoled and relied on visibility, individual will and public enactments, Savarkar in the same era would elevate the powers of secrecy and anonymous collective organisation for a counter political philosophy. Two years after the limited publication of Savarkar’s manifesto Essentials of Hindutva, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) was founded in 1925 to realise this mission.

Savarkar, from his earliest writing on the Mutiny or Indian War of Independence to his last work Six Glorious Epochs was fixated on history and warfare, in particular. In fact, much like other political actors of this era, including Jawaharlal Nehru, history and its writing became the primary template and vehicle for conveying political ideas and visions. Gandhi, by contrast, was unique, because he thought little of history, as history for him was but an account of violence. Non-violence being event-less in nature and even ordinary left little to no record but was the silent large canvas upon which wars were written over.

As preeminent innovators and authors of politics, Gandhi and Savarkar named their politics uniquely after their own visions. Satyagraha or the insistence on truth was a new word that mobilised the politics of the plain for the dismantling of the most powerful empire in modern world history. Savarkar’s Hindutva, a relatively new word with limited circulation in his time, gave a definite set of meaning and a sharp political valence of militant Hindu-ness as nationality.

If Gandhi saw India as a civilisation, then for Savarkar, India was a battlefield in search of its true master. As an atheist, Savarkar instituted Hindutva as a political monotheism. As a believer, Gandhi embraced religion to court friendship and fraternity across denominations.

In Gandhi’s voluminous collected works, Savarkar rarely makes an appearance. Gandhi, too, is a silent referent in Savarkar’s many writings and publications. Unlike Gandhi’s loud, public and even bitter disputes with his nemesis Babasaheb B.R. Ambedkar and on the caste question, the Savarkar-Gandhi differences remain intimate but entirely unspoken.

Also read: Indian liberals have no strategy to counter RSS’ own brand of ‘Hindutva constitutionalism’

New fathers for New India?

The current debates do not centrally concern Gandhi. Yet Gandhi, like in their lifetimes, has become the vehicle to stage Savarkar. Although the moving spirit for the rise and entrenchment of the RSS in independent India, Savarkar’s public life is rather more recent.

In his confession, Gandhi’s assassin Nathuram Godse declared that India had two defining, if opposite, ideas of Gandhi and of Savarkar. He respected them both, going as far as to touch Gandhi’s feet before pulling the trigger. Since Gandhi’s assassination, these themes remain alive and visceral. The point is not to rehearse or revisit any connection between Savarkar and Godse. Rather, the assassination disallowed any easy or public life for Savarkar.

Precisely because history has conveyed political ideas, India’s official and national history has been the site of contestation since 1990 and with rise of Hindu nationalism as an electoral force then and political hegemon today.

If Gandhi was the face, name and supreme agent of free India, Savarkar is the unacknowledged ‘father of New India’. Whether through public history, commemorations in portraits and statues especially in government and public buildings or in controversies regarding the past, these are all but mechanisms to instal Savarkar. To that end, Gandhi remains indispensable as without the Mahatma, there is no Savarkar.

The author’s new book ‘Violent Fraternity; Indian Political Thought in the Global Age’ will be out next month. She teaches modern Indian history and global political thought at the University of Cambridge. She tweets @shrutikapila. Views are personal.

(Edited by Prashant)