Two preliminary mandatory readings for any undergraduate student of history are EH Carr’s What is History and RG Collingwood’s The Idea of History. Carr critiqued a deterministic, fact-based study of historical events and argued that history is a study of selective events that have been given assumed importance according to the biases of the historian. Quite simply, history is written by the victors.

Collingwood forwarded a more empathetic study of history that called for ‘historical reenactment’, where instead of assigning present morality to characters of the past who did not live and function in the same socio-economic and political conditions, we try to understand their motivations through their perspective.

There has been a renewed interest in the Mughals among the masses, which would have delighted any medieval Indian historian. But alas, the interest is anything but academic. A recent article in ThePrint by Dilip Mandal entitled Mughals failed India in science. Just see what Europe did between 1526 and 1757 is perhaps not a communal attack on the Mughals. But it is certainly an ahistorical, Eurocentric understanding of Indian history that echoes the opinions of colonial historians.

Also read: Portuguese Gujarati Bania companies, South Indian bronzes—how Africa helped India become rich

Colonisation and science

Most modern disciplines like sociology, political science, and anthropology were developed during the height of European expansionism and inherently suffer from colonial biases. Recently, in the post-Black Lives Matter era, there were calls to decolonise the sciences. Renowned publications, such as the National Geographic, in the West apologised for suffering from the ‘white gaze’ in their past publications. The fact that the Nobel Prizes disproportionately recognise contributions only from institutions situated in the West and that no black scientist has won the Nobel in science can be a jarring testimony to the continuing hegemony of the West in academic discourse. The recent news of scientists from Tel Aviv discovering that plants emit certain frequencies under stress is closely reminiscent of Indian physicist Jagadish Chandra Bose’s work from a century ago. It was disregarded by the western academic fraternity at the time for suffering from animistic ideas of the East.

One has to remember that advances in western medicine were not solely a product of ‘scientific temper’ but also a direct result of colonisation. The push to discover the drug for malaria, quinine prophylaxis, came because colonial armies were dying from the disease in west Africa. Jonathan Ross, a doctor born in India who served in the colonial army, admitted that “in the coming century, the success of imperialism will depend largely upon success with the microscope.”

The gift of western medicine was not out of benevolence to the colonised; it was an inevitable fallout of imperialism. Moreover, western medicine did not develop unilaterally in Europe. Colonial expansions exposed the Europeans to vast knowledge of indigenous communities, which they blatantly stole and repackaged in the absence of international treaties like the Nagoya Protocol.

For example, an enslaved labourer in Jamaica found a plant, later named Apocynum erectum, that was suspected to be poisonous by the colonial masters. It was a crime for which he was hanged. Eventually, the plant was developed as a cure for ringworm. Even in post-colonial times, the contributions of non-white communities to the development of western medicine have been erased—the most famous example of this being Henrietta Lacks. Historian David Arnold has written extensively on the colonisation of the human body. Therefore, any idea that western medicine developed purely out of some essentialist trait in Europeans that was developed by their Protestant ethic is highly misleading.

It is pertinent to also understand how industrialisation in England was a direct consequence of the vast expanse of land and resources that were suddenly at the crown’s disposal due to colonisation. The colonies not only provided resources for industrial goods back in England but also served as markets when the European markets were saturated. The steam engine, which has been hailed as an engineering marvel, became the symbol of economic exploitation in the colonies later on. The first stock exchange in Amsterdam was set up to invest in the trading stocks of the Dutch East India Company and was a direct result of mercantilism, which is quite antithetical to the notions of free-trade capitalism.

Also read: You know about 1857. But not enough on the military labour market and caste in EIC army

Mughal emperors—wine, women, song?

One has to stop comparing apples with oranges if one wants to engage in a serious study of comparative history. Scientific inventions in the West that were individual feats cannot be hailed by blaming the Mughal state. An empire has to be compared with an empire.

If the rise of capitalism and the “scientific spirit” is to be applauded in medieval Europe, then one has to remember that it was not a movement spearheaded by the state. Protestantism started when professor of moral theology Martin Luther published a document entitled Disputation on the Power of Indulgences against the Catholic Church. Nicolaus Copernicus, who developed the heliocentric model, was a member of the Catholic Church.

Moreover, it can be argued that the royal class in Europe, be it the German princely states or Henry VIII in England, clamped down on the Catholic Church to expand their own political authority and not out of any proclivity for the sciences.

No one can dispute that the caste system created Brahmanical hegemony over knowledge in India, which undoubtedly was an impediment to innovation. But religion cannot be effectively argued as imbuing scientific temperament en masse. The Protestant ethic may be one of the contributing factors that catalysed innovation and capitalism in medieval Europe, but it does not conclusively explain why advances in philosophy, astronomy, mathematics, and medicine happened in ancient India or even ancient Greece.

The portrayal of the Mughals as despots who spent only on military conquests and monuments through brutal extraction of land revenue is taken from Karl Marx’s idea of ‘Asiatic despotism’, which has been widely refuted in academic circles. Historians such as BD Chattopadhyaya argued that the term ‘feudalism’ was a uniquely western concept that was blindly adopted into the Indian context without considering its own distinct socio-economic systems. Such systems included the existence of multiple rights over the same plot of land, where the emperor did not own all land. As far as the brutal extraction of revenue is concerned, the British far outplayed the Mughals.

Science, technology and Mughal courts

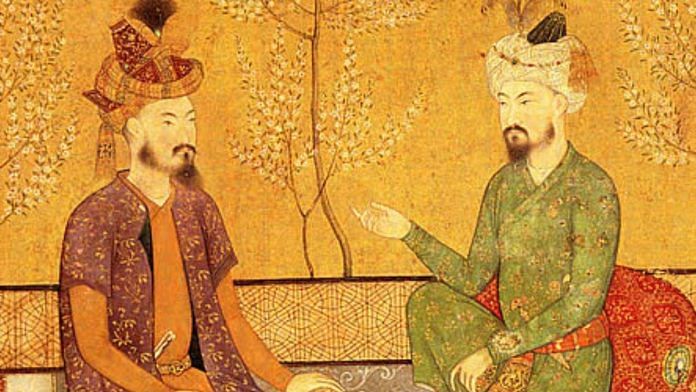

The hedonistic portrayal of Mughal emperors is not uncommon in colonial historiography. However, historians have since tried to combat perceptions steeped in racial and cultural prejudice. Mughal Emperor Babur famously used the astrolabe in wars. The first astrolabe was constructed during the time of Sultan of Delhi Feroz Shah Tughlaq before 1388, and its use was famous across the Islamic world. The device was an achievement in both metal and woodwork, mathematics, and astrology.

After Humayun’s conquest of Gujarat, he honoured and admitted Ikhtiyar Khan into his court for his knowledge of math and astronomy. The Ain-i-Akbari mentions a long list of subjects like theology, ethics, history, politics, accounting and arithmetic, mensuration and agriculture, engineering and astronomy, domestic science and medicine, logic and philosophy, and physical and mechanical sciences. Akbar even made mathematics and astronomy compulsory subjects in schools.

Arab merchants, who came pouring into the western coast of India after the ‘Arab invasion’ of Sindh, brought with them works on Euclid geometry and Ptolemaic astronomy. Al-Biruni, Iranian scholar, claimed that he translated the Euclid’s Elements and the Almagest by Ptolemy into Sanskrit, although those works have been lost.

There was also the confluence of the Unani and Ayurvedic systems of medicine. One does not even have the space to cover the strides that were made in the shipbuilding industry, metallurgy, paper production, and of course, the introduction of Rahat (the Persian Wheel).

The scientific renaissance that happened later on in the 18th-century court of Awadh was based on the legacy created by the Mughals. One of the most important schools of scientific learning in India at the time was known as Firangi Mahal in Lucknow, which published research on Euclidean geometry, mathematics, and astronomy.

There had been a long-established tradition of patronising scientists and scholars in the royal courts across the Islamic world. The libraries of the Nawab of Awadh, Tipu Sultan, Khuda Baksh, and the Raza Library in Rampur are famous examples of academic culture flourishing in the country. It was impeded by the British.

Arnold, in his book Science, Technology, and Medicine in Colonial India, argued that the East India Company failed to provide adequate patronage for science and technology because of their focus on generating profits. The famous drain of wealth theory by Indian political leader Dadabhai Naoroji covers the systemic deindustrialisation that happened due to the onslaught of imperialism. With such a historical backdrop, it becomes unfair to compare industrialisation in South Asia and England.

Also read: For first 300 yrs of their history, Ahoms were more Thai than Indian. Here’s how they changed

Cultivating a historical perspective

In the 1700s, India’s share of world’s GDP was estimated to be 24.4 per cent. Britain’s share was 3 percent. Such high levels of productivity cannot be explained against the backdrop of innovation stagnation.

Of course, one could argue that most innovation during the Mughal era happened in the fields of agriculture and trade. But this line of argument belies a cultural bias that is itself a product of western scholarship on what kinds of innovations are inherently valued. Historian Irfan Habib has argued against using ideological reasons and, instead, cited economic factors for certain inventions not taking off in India as they did in the West.

For example, a large supply of skilled labour did not necessitate industrial innovation in India at the scale that it did in Europe. Indian merchants were already abundantly rich and thus did not see the utility in investing in technological innovation. Moreover, India did not have an abundant supply of coal, which was indispensable for the industrial revolution in England.

This article was not written in defence of the Mughals, for the need to defend emperors long dead eludes me. Instead, the objective was a more nuanced reading of history that transcends colonial perspectives, embraces diverse schools of thought, and resists succumbing to contemporary political narratives. We need to stray from essentialist arguments while explaining the history and culture of a region.

In India, there has never been a rigid separation between the sciences and religion. Knowledge of math and astronomy was used to construct both secular and religious monuments. An example of this in present times would be Indian households worshipping a new laptop or car that they purchase.

It is also important to remember that terms like “renaissance,” “revolution,” or even—in regards to Indian history—grandiose titles like “First War of Independence” or “the dark age,” which connote sudden cataclysmic change, are manufactured by writers. In reality, historical events are the product of gradual changes over time that do not have such rigid periodisations. Similar “revolutions” and “cultural renaissances” happened all over the world at different points in history. They simply aren’t written about in the same manner as the history of Europe.

Mayurpankhi Choudhury holds a BA (Hons) degree in History from Lady Shri Ram College for Women, New Delhi, and a Master’s Degree in History with a specialisation in Medieval History from Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. Views are personal.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)