Textbook wars are back in India. The row over NCERT’s alleged decisions on what is to be added and what is to be deleted from a school history textbook is now new proof that symbolic politics is the new realpolitik.

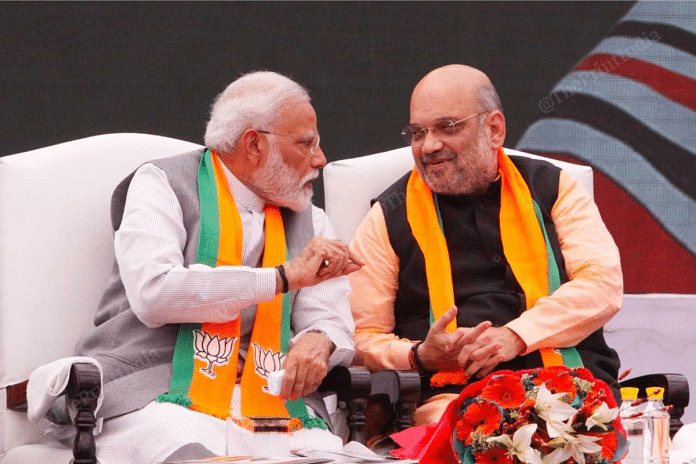

Alongside, India’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government is also giving itself unchecked powers to be the supreme arbiter of truth — by fact-checking the content put out by internet intermediaries. It has the power to get them to take it down too.

Seen together, it is an all-out capture of content — official and unofficial. This government, more than any other, understands that content is politics and that there is a dotted line between content and dissent.

With just a year left for the next general election, this understanding is critical.

Also read: 40 yrs ago, the Left mercilessly massacred Dalit Bengalis. Now, it’s back to haunt…

Not the first time

The omission of Nathuram Godse, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) ban, Mughal history, and the 2002 Gujarat violence from 2023-24 academic year’s textbooks has now prompted over 250 historians, who have condemned it and asked for the changes to be withdrawn. The government calls it syllabus rationalisation aimed at lightening the load for students during Covid times.

But it’s not the first time the BJP government has done this. Under former PM Atal Bihari Vajpayee, the National Museum changed the name of the Indus Valley Civilisation to Saraswati-Sindhu Civilisation, and the name of a travelling exhibition from “Gupta Period Art” to “Hindu Art”, former curator for the Indus Valley artefacts D P Sharma told me in an interview at that time.

Historians who had written school curriculum in the previous governments were removed. Their books were withdrawn. New appointments in the cultural and curriculum boards were made.

Before the BJP, Congress governments inserted their own mythologies into textbooks. One was how the Great Depression in America was caused by capitalism, and didn’t occur in the USSR because of its socialist economics. In West Bengal, the Left Front buried the Marichjhapi massacre.

Textbook wars are outdated. They assume — wrongly — that school children sit in the classroom in a vacuum with no other portals available for knowledge construction. In the digital era, a child is learning to scroll through YouTube videos and Reels much before they hold an NCERT textbook in their hands. By the time they reach middle school, knowledge of history is streaming in from all directions — oral histories, family histories, museums, memorials, books, songs, folklore, Google searches, popular media, and yes, even politics.

Of course, textbooks play a key part in defining official history, but the powerful tool of basement history — factual and fantastical — is where things are headed. That is how collective memory is being constructed like claiming Maharana Pratap actually won at Haldighati. So, this war has to be fought on multiple fronts. Academic historians have to leave the comfort of their libraries and archives every now and then and occupy informal, popular history spaces too.

And that is where the government’s fact-check mission comes into play. It will give them the power to take down online content that is inconvenient or content that is building a ground-up counter-narrative — on events of history, politics, or economy.

Also read: Battle over history just got a giant new classroom in India—YouTube

Wash, rinse, mess it up

There is no Indian exceptionalism to the rewriting of history. Across the world, many countries — from Japan to Spain, South Africa to Belgium and Rwanda — have grappled with troubling, inconvenient histories.

Recent research has shown that American history textbooks have a North-South divide in the way the Civil War was written about. In the aftermath of the Black Lives Matter movement, there is now a push by the advocates of critical race theory to dismantle the subtle signalling of White supremacy that resides in American and British school textbooks. Parents are fighting in school boards across America to resist these changes and saying their children should not be portrayed as racists just because they are Whites.

History is constantly washed, rinsed, and made messy again. Headbutting over history is essentially a debate about power and not an argument over dates and names.

There was a sort of “pact of forgetfulness” — an unwritten agreement that you don’t ask the other where they were during the dreadful Franco years. Japan has also dealt with the difficulty over remembering its militaristic past by often sidestepping and disremembering much of the 20th-century past, historians have noted.

South Africa tried the Truth and Reconciliation Commission to resolve and repair in full public gaze.

The many histories

When the truth is omitted or is under political attack, the most effective way to fight has been to build robust counter-narratives.

Rwandans built museums and memorials, produced books, documentaries, and radio programmes to commemorate the Hutu-Tutsi massacre. If in future, their history textbook omits the massacre, it won’t lead to erasure from collective memory. If India removes Partition violence from its school textbooks, it won’t get wiped clean from national memory. That generation has passed on stories to their children about what happened.

That’s the power of informal history. It knows how to survive. And in the digital era, it knows how to travel too. Unfortunately, this is also the space where propaganda lurks. Capturing these dark corners is as important for the community of history communicators.

“We are not trying to change history. It happened. Not telling what happened does not change the fact of its happening. What we would like to change are the attitudes that keep us in that place of omission, where one part or ‘side’ of history is perceived as the whole,” Julia Adeney Thomas wrote in a chapter in Museums and Memory.

“Gone

Buried

Covered by the dust of defeat—

Or so the conquerors believed

But there is nothing that can

be hidden from the mind.

Nothing that memory cannot

reach or touch or call back.”

Don Mattera, a South African poet quoted in the District Six Museum, Cape Town, South Africa, 1987.

Rama Lakshmi is Opinion and Features Editor at ThePrint. Views are personal.

(Some research in this article were part of the author’s essay in the IIC Quarterly in 2010.)

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)