Trade negotiations between countries or trade blocs are only slightly less complicated than border negotiations with neighbours.

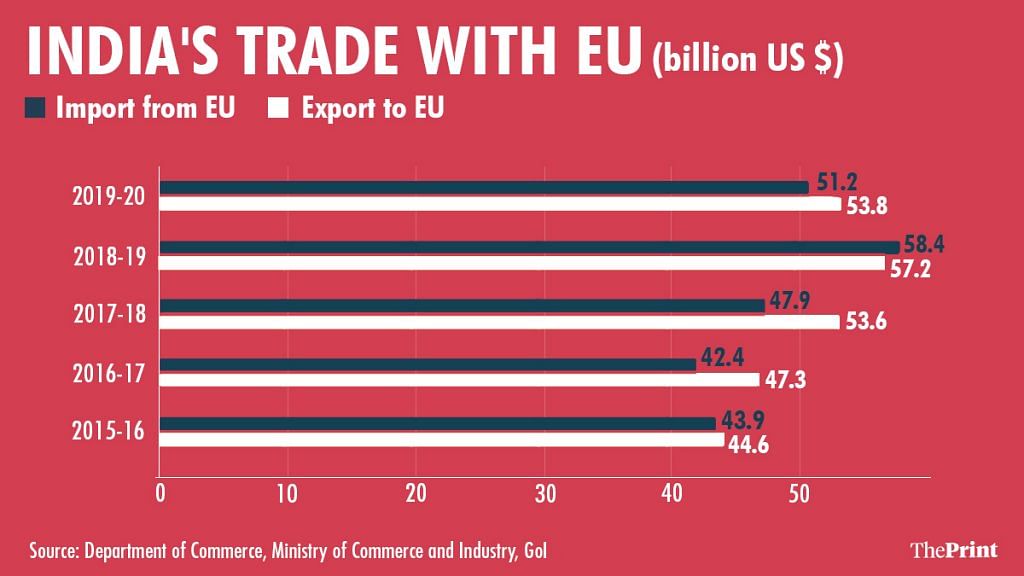

The European Union (EU) is an important trading partner of India. In 2019-20, Indian exports and imports to the EU were $53.8 billion and $51.2 billion respectively, making India a net exporter.

India and the EU began their Free Trade Agreement (FTA) talks in 2007. The trade deal was ambitious as it proposed to look beyond just goods to trade in services, investments and economic cooperation — in the form of a Broad-based Trade and Investment Agreement (BTIA). From 2007 to 2013, there were 16 rounds of formal talks, but an agreement could not be arrived at due to major differences on several issues. These included the extent of market access, tariffs on automobiles and automotive parts, dairy, alcoholic beverages including wines and spirits, and harmonisation of regulations on data protection and cross border flow of data. Another sticking point was the Indian demand for a liberal visa regime and free movement of professionals from India to the EU.

On 8 May 2021, the EU and India agreed to resume the stalled trade negotiations. In addition to the issues discussed in earlier rounds, it is felt that this new round will also include talks on policies on public procurement of goods and services, regulations on intellectual property rights, and a roadmap to address issues of sustainable development. Labour rights may also figure in the negotiations.

Agriculture is also likely to figure prominently in the talks. We discuss some of the contentious issues on agriculture and allied sectors in these negotiations.

Also read: UK begins work on free-trade deal with India, aims to double $33bn trade

The dairy question

Given that the EU has an export interest and has a surplus in dairy products, it would like to include it in the FTA. The EU would be looking towards the rapidly expanding middle class in India (now perhaps not so true due to the economic slowdown since 2016-17 and Covid-19 pandemic) and the scope of exporting higher value dairy products like cheese, yogurt, ice cream, etc.

The scenario is quite different in India.

While India’s dairy sector is one of the biggest in the world, it is dominated by small and marginal farmers who rear just a couple of buffaloes and cows. In 2017-18, milk production was just about 1,200 kg per cow per year in India, about 50 per cent of global average (Report on Policies and Action Plan for a Secure and Sustainable Agriculture: Submitted to Principal Scientific Advisor to Government of India, 2019). In 2019, the average milk production per cow per year in EU was 7,346 per kg. Yet, the sector provides a livelihood to more than seven crore people. Thus, from that point of view, the sector is sensitive. Moreover, due to India’s large consumer base, the export interest is limited.

At present, the import of milk powder invites basic customs duty of 60 per cent. The duty on the import of cheese, yogurt, ice cream and whey is 40 per cent while buttermilk attracts 30 per cent duty. The EU would like lower duty on various dairy products.

In fact, one may recall that recently, during the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) negotiations also, the dairy sector was one of the major sticking points. The push for opening up the dairy sector had come from New Zealand, which exports about 93 per cent of its annual milk production in the form of various dairy products.

Finally, India pulled out of the RCEP at the last moment.

Also read: Biden’s US is done engaging with China. This is what India should do now

Liquor duty

The second item of interest in the EU-India trade talks would be alcoholic beverages. The earlier EU interest in exporting Scotch whisky at reduced tariff is no longer existent because of Brexit, but the interest in exporting a wide variety of wines and spirits continues.

The EU would be eyeing the fast-growing Indian market for its alcoholic beverages due to rising consumption of liquor in India. Alcoholic beverages earlier attracted a duty of 150 per cent. The Union Budget of 2021-22 reduced the basic customs duty to 50 per cent, but 100 per cent Agriculture Infrastructure and Development Cess (AIDC) was imposed. This was perhaps done in anticipation of trade negotiations with the UK in the post-Brexit scenario. So, the only space available to the EU negotiators would be reduction in the 50 per cent basic customs duty.

The Confederation of Indian Alcoholic Beverage Companies (CIABC) will oppose any serious reduction of duty, but in order to gain negotiating space, India may well agree to some reduction on the more expensive categories of wines and spirits. Since liquor is not covered by the GST regime, the state governments impose hefty excise duties because it is an important source of revenue, especially due to the impact of Covid-19 on other revenue sources. EU negotiators would like liquor to be included in GST, but that may not be possible in the near term due to GST revenues being much lower than estimated.

Also read: Next gen FTAs are all about labour, environment protection. Only way India can edge China out

India needs trade advisers

While the tariff barriers are widespread, there are several non-tariff barriers on the agriculture sector per se in the form of sanitary and phytosanitary standards. As a member of the World Trade Organization (WTO), most Indian exporters follow the Codex standard for export commodities. However, in the past there have been instances where the EU has imposed standards, more stringent than the WTO ones, which have adversely affected India’s agricultural exports. These issues need to be addressed in the FTA.

Last but not the least, there is an administrative issue also. In the past, before entering into negotiations, the Ministry of Commerce consulted relevant ministries about the tariffs and liberalisation of the import regime, but most ministries do not have much expertise and long term memory on international trade so they oppose every proposal of reduction of tariff. The consultation with the states on tariffs on agricultural produce is also not comprehensive. In any case, the states have even less expertise in matters of global trade negotiations.

Since the farmers are directly impacted by the decisions on tariffs, it is necessary that states get expert advice from outside the government. To this end, the development of academic institutions and think tanks specialising in international trade issues seems imperative. The ministries at the Union government could also use the route of lateral entry to appoint professionals who are well-versed in different areas of trade negotiations such as investment, non-tariff barriers and digital technologies.

Finally, the trade negotiators need to be groomed for much longer stints than the current deputation rules of the Government of India allow.

Siraj Hussain is Visiting Senior Fellow, ICRIER. He retired as Union Agriculture Secretary. Jayant Dasgupta was India’s Ambassador to the WTO. Views are personal.