The state must show greater sensitivity in dealing with children participating in political violence and make efforts to rehabilitate them.

Many analysts hold that the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) is in the throes of a new wave of militancy—one that is driven by the growth of the internet and social media that allow militants to broadcast their propaganda in real time.

Social media-driven militancy

In 2015, for example, a series of images of young boys brandishing guns in the jungles and orchards of south Kashmir went viral on social media. The imagery widely provoked shock and horror. Until that point, the old insurgency of the 1990s was considered successfully contained, and young Kashmiris had become increasingly disenchanted with violence.

During the period between 2008 and 2015, prolonged protests had provided a platform for the expression of discontent, thereby reducing the need for local boys to join militancy. Indeed, the number of local Kashmiri recruits had decreased considerably in the early 2000s. By 2010, the number was down to six.

The wielding of social media in 2015 showed a drastically different modus operandi from that of the old militancy in Kashmir. Until those pictures came out, there was little public discourse about local militancy.

In the past, militants remained in hiding and away from the limelight, either for the lack of access to media or to avoid being caught by security forces. The new crop of militants, however—armed with the power of instant fame through social media—seem more eager to make a public display of their involvement in armed jihad.

Also Read: Indian Army made way for government to resolve Kashmir, but politics failed

The rise of a child militant

At the forefront of this new pattern in Kashmir insurgency was Burhan Wani.

Throughout 2015 and the early months of 2016, Burhan Wani captured the public imagination in Kashmir through social-media pictures and videos that went viral in the state.

The power of these images was so strong that the issue of militancy not only established itself in the popular discourse but also marketed itself as a commodity, similar to how a new product in the market would entice consumers.

However, while Burhan Wani’s poignant life story and foray into militancy became a catalyst for fresh recruitments, an important aspect of the phenomenon he embodied escaped the attention of many: that Wani was a minor at the time of joining the ranks of Hizbul Mujahideen, akin to the ‘child soldiers’ of the militancy in the 1990s.

After Wani, many young boys who had not reached adulthood at the time of recruitment joined various extremist outfits.

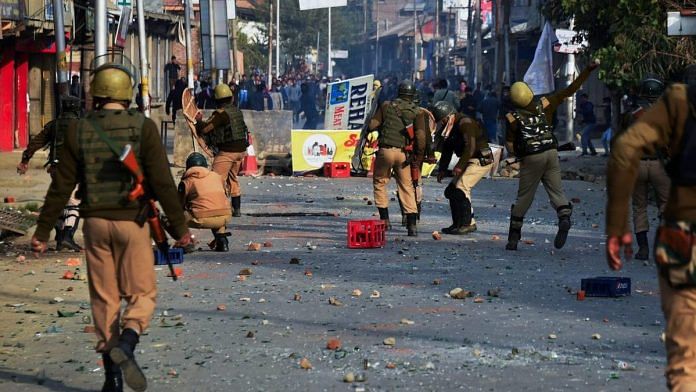

During the unrest of 2016, triggered by Wani’s killing, a new dimension of the conflict emerged: more and more minor children were taking part in street protests and enforcing shutdowns.

The militant groups used the juveniles as tools of propaganda and to recruit more young boys into their ranks.

The involvement of children in acts of violence, for example, stone pelting and arson, was then followed by a heavy-handed crackdown of security forces.

In the absence of a juvenile justice mechanism, the law-and-order apparatus failed to differentiate between children and adults, in turn provoking an ever greater degree of anger amongst the Valley’s people.

Some of the children who were involved in stone pelting and other forms of protests were eventually lured into the ranks of militancy, due to the government’s failure to rehabilitate and steer them back into mainstream society.

Also Read: Why even an ex-IAS officer like Shah Faesal sympathises with murderers of his kith and kin

Startling number of child recruits

According to data accessed from the J&K police, at least 24 children below the age of 18 were recruited by various militant groups from 2010 to July 2018.

Additionally, a news report quoted the locals from south Kashmir—where the new wave of militancy is most intense—stating that the police underplays the number of new recruits: “Locals aware of the happenings differ with the figures. They say around ten of these militants are below 18 and police avoids mentioning their age correctly.”

The police data only mention the children who may have been arrested or detained and the militants who have shown up on the radar of intelligence units.

However, there are many more juveniles who are involved with groups such as Hizbul Mujahideen, Lashkar-e-Taiba and Jaish-e-Mohammad as over-ground workers providing logistic support, for instance, Mudasir Rashid Parray, as per reports, he was an over-ground worker for LeT commanders Abu Zargam and Abu Fanan.

The data maintained by the J&K police show that the first underage recruit in the new, social-media driven wave of militancy was its poster boy Burhan Wani. At the age of 15, he was recruited by Hizbul Mujahideen, and by 2013, he had become the leading figure of the group.

Lost to conflict: Burhan Wani

In 2010, 15-year-old Burhan Wani disappeared into the jungles of South Kashmir to join the Hizbul Mujahideen group.

Wani was amongst the first few recruits in the new wave of militancy. In 2010, the number of local Kashmiris in militant groups was very low and most of the active militants were foreigners.

In 2013, after the death of the erstwhile leader of the group, Wani became the commander and leader of Hizbul Mujahideen.

He became the face of the group and released multiple pictures, posing with guns along with his colleagues, and video clips explaining his reasons for joining the militancy and calling on more youth from the valley to join them.

The videos and pictures he released became a game changer for the militancy in Kashmir, as they portrayed fearlessness amongst militants, attracting a new breed of young educated boys.

By Wani’s own admission, a moment of humiliation that he and his brother faced at the hands of J&K Police triggered his foray into militancy. He was allegedly beaten up by police officers over a petty charge. Seeking revenge, Wani joined Hizbul Mujahideen.

Wani’s case shows how the police’s misconduct in dealing with the youth can lead them to seek a violent recourse. It also shows how social-media presence can make terrorists out to be heroic figures seeking martyrdom under the rubric of jihad.

Moreover, Wani’s social-media presence took the idea of militancy to every household of Kashmir, and his rise into the leadership, albeit circumstantial, not only revived the militancy but also gave it an ideological and moral direction.

Naturally, he appealed the most to boys of his age and became an inspiration for their foray into militancy, as one analyst pointed out:

“Children who were not even in their teens in 2008–10 are now angry, politically disenchanted youth. The anger among these youth has been brewing and they found a ready hero in Wani. The heroism was worth it as Wani pushed the envelope by using new tech-savvy methods of recruitment, promotion and message delivery.”

Wani, exemplifies the term ‘child soldier’, as defined by the UN, whose deification has attracted more juveniles into their fold. Over the last few years, specifically after Wani’s killing, there has been a discernible trend of militant groups recruiting children.

Also Read: More killings, greater alienation: How the situation in Kashmir is slipping out of hand

The way forward

Responses of the state towards child agitators, particularly by the police and the judicial system, show a stark callousness. There is a dearth of creative and imaginative solutions to prevent these children from taking to militancy. The brutal treatment meted out to minors by security forces only serves to push them deeper.

Finally, the lack of an adequate and inclusive juvenile justice mechanism ensures that the children who participate in civil protests and stone pelting get radicalised inside the police lockups, where torture and misconduct are rampant.

The justice system, thus, further alienates these children from society and the state.

The state must show far greater sensitivity in dealing with children participating in political violence, and it must make efforts to protect, care for and rehabilitate them.

The author is an associate fellow at ORF.

This is an edited extract from his research paper Children as Combatants and the Failure of State and Society: The Case of the Kashmir Conflict. This has been republished with permission from Observer Research Foundation (ORF). Read the full paper here.

Print has gone crazy. How a terrorist is called soldier? Shame in you

Not sure if Burhan Wani could be considered a child. However, I saw two photographs, juxtaposed. A young man standing framed against the mountains and sky of his beloved Kashmir. And of his mortal remains. Felt a deep sense of loss and sadness, not sharing the gloating emotion of the veteran who tweeted them. At that stage, few could have foreseen how the killing of one more young man would be such a decisive turning point. If one is not mistaken, that is when the use of pellet guns, people losing the priceless gift of their eyesight, became widespread. It is no longer considered patriotic or politic to express pain or sympathy for the suffering of the Kashmiri people.