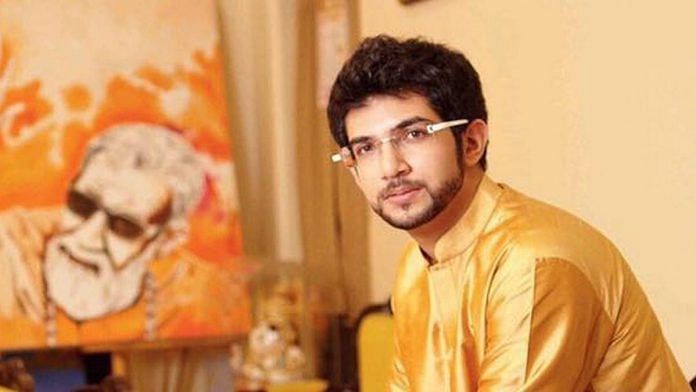

Aaditya Thackeray, Maharashtra’s minister for tourism and environment, is on a roll-and-roar political cycle. He has had the perfect political debut, but things are far from being easy for him. He has been uncharitably compared to Rahul Gandhi and dismissed as a tree-hugging, anti-infrastructure millennial. He has the onerous task of convincing India that he and his father, Uddhav Thackeray, have shaken off his party Shiv Sena’s Hindutva past and yet is strident enough to take on Amit Shah’s BJP.

But within a month of coming to power, his government has taken up one of his pet projects.

Night-binging, Aaditya Thackeray’s elixir for Mumbai, was recently cleared by the Maharashtra cabinet headed by his father, Shiv Sena president and Chief Minister Uddhav Thackeray. Shops, clubs and restaurants in non-residential areas of India’s financial and entertainment centre, Mumbai, can stay open 24×7 allowing its generation X, Y and Z “more space and time to unwind after hours of work,” says the young politician about one of his dream projects.

But reinventing Mumbai’s nightlife has never been about all play and no money for the millennial leader. “These areas could be up all night and as per international norms, you employ one person for eight hours. Twenty-four hours demand the employment of three people. The revenue goes up for the state businesses, tourism increases, more employment is generated,” he told Gurmehar Kaur for her book The Young and the Restless: Youth and Politics in India. Aaditya Thackeray suspects his idea – first mooted in 2013 – for rescuing Mumbai’s nightlife from beyond boring was deep-frozen because a few politicians thought that he was slyly sneaking in a “crazy culture change”.

Thackeray junior was not being salty. On cue, senior BJP leader and six-time MLA from Mumbai, Raj Purohit red-flagged his party’s concerns about the project’s moral fallout, claiming it would “give rise to an alcohol culture, corrupt the youth and lead to an increase in crimes against women; there will be thousands of rape cases like Nirbhaya,” he prophesised. Shiv Sena’s now ally, the Nationalist Congress Party (NCP), argued that “if shops, restaurants and malls are kept open through the night, it would increase the burden on Mumbai’s policemen.”

Aaditya Thackeray finally got his way. “Keeping Mumbai open at night is a huge deal for him because it will boost his popularity among the youth; more than one-fifth of Maharashtra’s population is below 30, and for any political party to remain relevant in the state, their approval is critical,” a 60-plus Shiv Sena leader told ThePrint at Shivalaya, the freshly minted minister’s bustling office in South Mumbai’s Nariman Point that is dominated by a large portrait of his grandfather and Shiv Sena founder Bal Thackeray. “The 29-year-old is our safety net for the future. Not only does he have age on his side, but unlike his father, Aaditya is not a reluctant politician,” he added.

Also read: Uddhav’s Shiv Sena has had a change of heart. It now waits for Muslims to come around

Youth connect

Aaditya Thackeray is young but he is not pushing for a 24X7 nightlife for Mumbai just to be able to party. He is way too political for that.

“He is a hands-on kind of guy who works round the clock. Aaditya is a teetotaller, doesn’t party, politics is his big passion and our cadres have been revitalised by his enthusiasm,” says maternal cousin, civil engineer-turned-Shiv Sainik, Varun Sardesai, who handles Aaditya’s social media accounts.

Traditionally, the Shiv Sena drew its strength from a network of shakhas manned by workers who acted on the political directives coming out of Matoshree, the Thackeray clan’s heavily guarded bungalow in Bandra East. Now, Aaditya Thackeray uses WhatsApp, Twitter and other social networking platforms to communicate directly with them and the voters. He is developing his own constituency of young turks within the Shiv Sena. “He has also started a WhatsApp group that has at least 20-22 of the young, newly elected MLAs from the three constituents of Maha Vikas Aghadi (MVA) – the Congress, the NCP and our Party,” reveals Sardesai.

But the importance of direct contact is not lost on the Thackeray scion. After the 2019 Lok Sabha election, he embarked on a 4,000-km Maha Janashirwad Yatra ‘’to take the Shiv Sena into every home in Maharashtra,” but essentially shed his and the party’s urban-centric image.

It’s the same energetic approach that he has now brought to governance.

Since joining the cabinet last month, Aaditya Thackeray has been seen and heard more than any other MVA minister. He targeted Prime Minister Narendra Modi on demonetisation by labelling it as the “biggest blunder in post-Independence India” and said that the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, which his party had embraced before committing to the MVA’s secular agenda, was “dividing the country.”

Also read: How Uddhav Thackeray shed his Rahul Gandhi image to be a Shiv Sena leader in his own right

Unlike Rahul Gandhi

Closer home, Aaditya Thackeray made a slew of high-profile announcements linked to the Birhanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC), India’s richest civic body that the Shiv Sena has controlled for nearly two decades: handing over 300 Maharashtra Housing and Area Development Authority (MHADA) homes to agitating residents of Mahul, a fishing village on the city’s eastern seafront affected by dangerous toxins released from oil refineries and chemical factories and introducing national-level syllabus in select government schools to improve the standard of education.

“Where are the trained teachers for this intervention,” asks Atul Bhatkhalkar, the vocal BJP MLA from Kandivali East in North Mumbai who also calls out Aaditya Thackeray on his U-turn on Mahul. “As recently as October 2019, just before the Shiv Sena formed the government, the BMC had moved the Supreme Court against the Bombay High Court order to pay either compensation or provide alternate accommodation to the people of Mahul. He is committing a fraud on Mumbaikars, by projecting himself as a go-getter.”

But Aaditya’s supporters in the Shiv Sena believe he is making all the right moves. “Correcting past mistakes will make him appear humble, someone who is in sync with the problems and aspirations of the common people, despite his privileged background,” says a member of the party’s youth wing, the Yuva Sena. “And it’s no walk in the park, one only has to look at Rahul Gandhi who, after more than 15 years in politics, sleeping in mud huts and eating at roadside dhabas, is still trolled for not being a simple ‘tea-seller’.”

Also read: Uddhav Thackeray as CM is good news for Maharashtra’s forests, wildlife and animal lovers

A creative gene

Aaditya Thackeray graduated in history from St. Xavier’s College in Mumbai and followed it up with a law degree. “He was an above-average student, conscientious, well-read and deeply interested in modern Indian and Maratha history,” recalls professor Avkash Jadhav, who taught him at St. Xavier’s and went on to become a mentor and friend to the Thackeray scion. In 2012, Jhadav, also an environmental and cultural activist, was nominated to the BMC by the Shiv Sena as a councillor for five years. Photographer and film producer Atul Kasbekar who has known Aaditya for a long time describes him as a person of many parts – film buff, nature fanatic, music lover. A self-confessed Hrithik Roshan fan and lover of Urdu, Aaditya Thackeray has admitted to seeing Jodhaa Akbar no less than 50 times; until very recently, the caller tune on his mobile phone was a Michael Jackson number, the singer who specially went to pay respects to his grandfather Bal Thackeray to prevent trouble over his 1996 show. “He is a foodie, loves cricket and football and hates getting beaten in sports.”

Before politics, Aaditya Thackeray briefly dabbled in creative writing – his grandfather had started his career as an illustrator and cartoonist. In 2007, Aaditya published a poetry collection in English, only three poems were in Marathi, titled ‘My Thoughts In White And Black’, and followed it up next year with the release of ‘Umeed’ a music album for which he wrote the lyrics and lent his voice to a rap song. It didn’t rock the charts, but one track stood out for its message of cross-border peace and friendship – Sarhadon ke paar ja tu/Dosti ka haath baddha tu/Shanti ka sandesh le ja tu/Ja ja sandesa, ja ja sandesa. Ironically, Bal Thackeray prided himself on being a Hindu supremacist, regularly threatened to disrupt India-Pakistan cricket matches, banned Pakistani artists, and even chastised tennis star Sania Mirza for marrying Pakistani cricketer Shoaib Malik.

In October 2010, brandishing a sword that almost dwarfed his slight frame, Aaditya Thackeray, dressed in dusty-blue collared kurta and black trousers, made his political debut at the Shiv Sena’s annual Dussehra rally in Mumbai’s Shivaji Park as the head of the newly formed Yuva Sena. He was just 20 years old, but the phenomenal popularity his estranged uncle Raj Thackeray enjoyed among the Marathi youth could no longer be ignored by Matoshree – Raj Thackeray established his own outfit, the Maharashtra Navnirman Sena (MNS), in 2006 after splitting the Shiv Sena and hijacking its core ideology of ‘thokashahi’ (strong-arm rule).

The young debutante had to take on the rise of Raj Thackeray and make a bold statement.

A month before his official anointment as a red-blooded senapati, Aaditya Thackeray manned up his boyish image to take on his hyper-parochial and aggressive uncle Raj, by burning copies of author and St. Xavier’s alumni Rohinton Mistry’s Booker-nominated novel Such a Long Journey, which had been published 20 years earlier. “We have no issues with the book being available in the market but we don’t want it to be part of the Mumbai University syllabus because the book uses foul language against many things that we, in Mumbai, hold close to our hearts,” the college-going Aaditya had argued at the time.

The book was promptly banned. “As for the grandson of the Shiv Sena leader, what can – what should – one feel about him? Pity, disappointment, compassion? Twenty years old, the beneficiary of a good education, he is about to embark down the Sena’s well-trodden path, to appeal, like those before him, to all that is worst in human nature,” Mistry had said in response.

Also read: Shiv Sena was hated by Indian liberals as extremist Hindutva party. Now, it’s their darling

Image makeover

Fast forward to the present, and no one wants to talk about the Mistry incident. “He will always protect the dignity of our people, but by lawful means – Aaditya Thackeray was very young back then and people change, but that does not mean the Shiv Sainiks have lost any of their combativeness,” says Varun Sardesai, in defence of his cousin.

In 2015, Yuva Sena activists forced the cancellation of Pakistani ghazal artiste Ghulam Ali’s concert in Pune and Mumbai in protest against the “killing of Indian soldiers in border skirmishes”, and publicly blackened the face of columnist and a former BJP ideologue Sudheendra Kulkarni for hosting the launch of former Pakistan foreign minister Khurshid Mahmud Kasuri’s book. Their chief Aaditya Thackeray had insisted that the attack was “non-violent, democratic and historic”.

“The Shiv Sena was feeling stifled and slighted. Its muscle-flexing was aimed at embarrassing the BJP – Ghulam Ali and Kulkarni were just the fall guys,” says Prakash Akolkar, a Mumbai-based journalist and author. “The Sena had been the big brother in the saffron alliance of the pre-Narendra Modi era, but the roles reversed after the two partners fought the 2014 assembly election as rivals: The BJP won 122 out of 288 seats and the Shiv Sena a distant 63.”

Worse, the Shiv Sena lost its position as Maharashtra’s number one Hindutva party, its Marathi Manoos – son-of-the soil identity – sank like a stone under the weight of the BJP’s shrill nationalism.

Just when it seemed that the tiger – the Shiv Sena’s iconic mascot – had lost its stripes, Matoshree sprung a surprise. In a first since the Shiv Sena was founded in 1966, a member of Mumbai’s most powerful political family decided to contest an election: Aaditya Thackeray was chosen as the candidate from Worli assembly segment in South Mumbai.

“Times had changed, people did not want a leader who was aloof, but one who could take a risk and lead from the front, and so he (Aaditya) took the plunge. This was his idea and very much his decision. He informed his parents after making up his mind,” recalls Sardesai. Aaditya won by more than 70,000 votes. Campaigning on the Thackeray name, he insisted that he had no ideological differences with his father or grandfather, on Hindutva or nationalism, only his priorities were different: bettering lives of Maharashtra’s youth, including those who have come from other states, a titanic shift from the Shiv Sena’s former avatar as a party of bigots that regularly beat up migrants to show them who the boss was – currently the calling card of the MNS.

Once the Shiv Sena ‘un-friended’ the BJP on the issue of rotational chief ministership and formed the government with the Congress and the NCP, Aaditya Thackeray suddenly found he had some freedom to follow his own agenda – one that would focus on environment, farmers and the youth – and, in the process, rebrand the Shiva Sena as a reformist party distinct from its saffron competitors.

In October 2019, the Mumbai Metro Rail Corporation’s (MMRC) move to cut over 2,600 trees at Aarey Colony to build a car shed met with massive protests from the people of Mumbai, including Aaditya, who described the felling – which still went ahead – as “shameful and disgusting”. “How about posting these officials in PoK (Pakistan-Occupied Kashmir), giving them charge to destroy terror camps rather than trees?” he said on Twitter. MMRC boss Ashwini Bhide, who ordered the felling of trees, was transferred after the MVA took charge of Maharashtra. However, Thackeray junior’s tree-tantrum wasn’t without irony: Shiv Sena was part of the BJP-led coalition government in Maharashtra, the state environment minister belonged to his party, and had cleared the proposal in the first place.

“And why is he so quiet about the coastal road project, which green activists and fishermen insist will cause more damage to the environment? Is it because the project is being handled by the BMC and will earn the Shiv Sena huge amounts of money?” asks BJP MLA Bhatkhalkar.

But Afroz Shah, lawyer and green activist who led a people’s movement to collect garbage from Mumbai’s Versova beach in 2015, still believes Aaditya Thackeray’s heart is in the right place: “He has spent many weekends picking up plastic and other waste from the sea-shore as an ordinary volunteer, and you can see that nature vandalism really bothers him.”

Also read: Mumbai to stay open 24×7: More cities should follow or fix creaking infrastructure first?

The challenge ahead

Not everyone in the Shiv Sena is enthused with Aaditya Thackeray’s new-age political vision.

“These ideas may enthuse a section of well-heeled Mumbaikars and young students looking for a worthy cause. But as long as fiercely contested national issues – ‘illegal’ immigration, cross-border terrorism, Article 370, ‘urban naxalism’ – drive the BJP’s political narrative, Aaditya Thackeray will have to do more than save trees and go plogging. He will have to get his hands dirty,” says a Shiv Sena MLA who is secretly furious with Matoshree over the divorce with the BJP, and accuses Aaditya and Uddhav Thackeray of sacrificing the traditional USPs of the party – hardline Hindutva and regional chauvinism — for personal ambition.

The challenge then for Aaditya is to build a Shiv Sena that attracts new voters without alienating its core constituency. It’s a delicate balancing act, one which is already being tested within the framework of a three-party coalition government. His grandfather was a rabble-rouser who built a reputation by intimidating his opponents; his uncle Raj who recently launched his son Amit in politics, is a charismatic orator while his father is a soft-spoken consensual figure. Can Aaditya Thackeray really break free from the past while carving his own identity? What is apparent is that the tiger cub is now all grown-up and slowly earning his stripes in an unforgiving political jungle.

The author is an independent journalist. Views are personal.