Of the many brutal scars that Partition left on South Asia, perhaps none is as raw as the India-Bangladesh border today. In the wake of an anti-establishment revolution, Bangladeshi Hindus have seen brutal persecution and varying degrees of support and solidarity. Before and after 1947, Bengal saw many bouts of religious violence. But in many ways, these were the results of 20th-century nationalism, rather than the astonishing history of Islam in Bengal. Though Islam first arrived with Turkic looters and conquerors, it only became the majority religion of eastern Bengal through the grandest, slowest force of Indian history—the flow of the Ganga River.

From Sword to pen

In 1236 CE, the Tibetan pilgrim Dharmasvamin trekked down from the ice-clad Himalayas to balmy Bengal. Graduates from Bengal had helped spread Buddhism among Tibet’s clans, just when the region was emerging from political anarchy into a stable, monastery-dominated landed order. But there were rumours of catastrophe.

Arriving in Bengal, Dharmasvamin, to his horror, found that there had indeed been a disaster, and experienced its aftershocks first-hand. While crossing a river, he found himself sharing the boat with two Turk warriors. They asked Dharmasvamin to hand over his gold, but he indignantly refused and said he would complain to the local Raja. Furious, the Turks snatched his begging bowl and threatened to kill him. Other Buddhist pilgrims intervened and convinced Dharmasvamin to pay up to save his life.

Dharmasvamin’s experience wasn’t uncommon in 13th-century Bengal. After the consolidation of the Delhi Sultanate in the early 1200s, bands of young Turk warriors had ventured down the Gangetic Plains seeking plunder. Their fast-moving cavalry easily outmanoeuvred the ponderous infantry armies of Bengali rulers. They looted and burned Buddhist monasteries rich with centuries of donations and seized control of cities. Soon, the Turks became a tiny and conspicuously Muslim ruling class within a vast countryside.

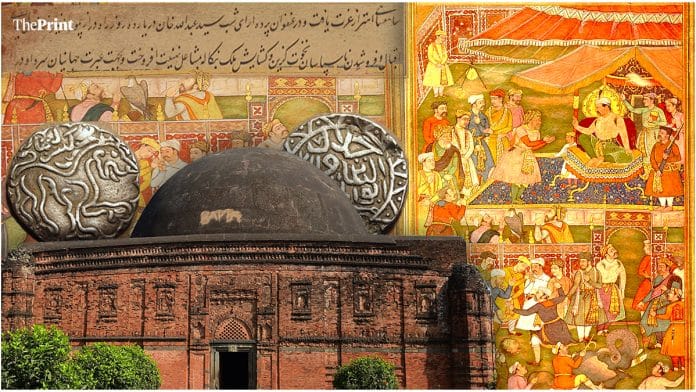

These early Muslim rulers of Bengal, as historian Richard Eaton writes in The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier 1204–1760, did not bother to adopt the culture of their subjects. Instead, their language and architecture looked toward distant Muslim power centres in Baghdad, Iran, and Delhi, leaving the countryside to be ruled by Hindu Kayasthas and the descendants of older Hindu and Buddhist lords. Over the next hundred years, Iranian and Central Asian Sufis—and their Indian disciples—spread through Bengal, converting frontier peoples, translating Sanskrit texts, and insisting on the legitimacy of Islamic kingship. Their support was desperately needed: as an isolated class of foreign rulers, the Bengal Sultans were always vulnerable to courtly intrigues and coups.

Such a coup was conducted by Hindu landlords in the early 1400s. One of their sons was placed on the throne of Bengal. In a compromise with urban Muslim warriors, the boy converted to Islam and was placed under Sufi tutelage. When he became Sultan Jalaluddin Muhammad (r. 1418–1433), he reoriented the Bengal Sultanate from its obsession with distant Iran, toward Bengal’s own rich culture. He patronised Brahmins, issued coins with motifs of the goddess Durga’s lion, and constructed mosques in Bengal’s traditional brick architecture. The Bengal Sultanate, rejuvenated, fended off an invasion from the neighbouring Jaunpur Sultanate and expanded toward Tripura and Odisha. But its subjects, like those of other Sultanates, remained primarily Hindu. Yet great geopolitical changes were on the horizon.

Also read: Olympics of medieval India were grisly, wacky, & thrilling. Elephant racing, polo, wrestling

The River of History

Throughout the 1500s, Bengal drew the attention of a new set of outsiders: the Mughals. The Bengal Sultanate had been established through military innovations in cavalry warfare but it was conquered by the Mughals’ military innovations in gunpowder. The Mughals made it clear that they would rule justly—if sternly. Villages that didn’t pay revenues were brutalised, but those that did could expect fair rates and even redress against corrupt collectors. According to Eaton, the Mughal ruling class, composed of large numbers of Rajputs, upper-caste North Indians, and immigrants from Central and West Asia, adopted a hands-off religious policy. There are records showing that zealous officials were punished for forcing Bengali rebels to convert to Islam. And when the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb Alamgir ordered temple destruction in the late 1600s, officers in Bengal and neighbouring Odisha generally ignored him.

Yet, at the same time, Bengal’s Muslim population was skyrocketing, thanks to a cocktail of factors. First, due to Mughal rule, a single regime now controlled river routes from Bengal to Delhi, which meant that Bengal’s textile and agrarian produce had an enormous new market. Second, the Ganga-Yamuna delta gradually shifted east, depositing tonnes of silt and annihilating dense jungles. This meant that in urban, Mughal-ruled western Bengal, Hindu merchants became fantastically rich, and had money to invest in expanding cultivation. With their financial backing, Bengali Sufi mystics moved east. They worked with settlers to clear the land, sow rice, and convert them to Islam.

The Mughal state granted land rights to Hindu financiers and their Sufi partners in return for fixed tax payments. As a result, Bengal’s agrarian output more than doubled over the 1600s. At the time, European visitors considered it the most fertile region on earth, where bags of grain were sold for almost nothing. It was this socioeconomic system—Hindu landlords in cities, Muslim religious figures and cultivators in the countryside—that British colonial power eventually shattered, twisting and turning it with horrific results. Under British rule, Bengal saw repeated, devastating famines—and the rediscovery and twisting of older historical sources.

Remembrance

Over the centuries, the character of Bengal’s Muslims changed considerably. From 1200 to 1400, they were a violent, urban ruling class; from 1400–1600, they were Indigenous Sultans and aristocrats; and from 1600 onwards, most Bengali Muslims were rural cultivators at the mercy of states—first the pan-Indian Mughal Empire and then the absolutely callous British Raj. As such, Muslims in Bengal have remembered their history in many different ways over time.

In the 15th and 16th centuries, for example, Bengali Muslim aristocrats found their position challenged by both Hindus and the Mughals. They wrote fantastical stories about earlier Sufi saints, claiming that they had destroyed temples and killed tens of thousands of infidels. As Eaton writes, the Moroccan traveller Ibn Battuta, a contemporary of these Sufis in the 1300s, says nothing about such violence. Instead, Ibn Battuta claims that Bengal’s Sufis were most active among hill communities. The Sufis’ own letters reveal they were close to Sultans and had a marked preference for Muslims and Muslim kingship. But they didn’t advocate genocide, as the modern Hindu and Muslim Right claim. In fact, it was during the Sultanate that the Neo-Vaishnavism of the preacher Chaitanya Mahaprabhu became popular in Bengal, perhaps the first mass movement of congregational Hinduism in northern India. (This is all an interesting contrast to how the Islamisation of Kashmir, which took place just before, was remembered.)

Historical memory is a flexible and ever-changing thing. From the 17th century onwards, newly converted Bengali Muslim farmers told new stories about the same Sufi saints. Far from claiming they were jihadis or ghazis, they praised the Sufis for miracles, for clearing forests, and for teaching them to cultivate rice. In a Sanskrit text, the Sekaśubhodayā, Eaton reports that Sufis are described as natives of Madhya Pradesh, who are sent to Bengal by Allah (called pradhāna-puruṣa, Great Person). Dazzling the ancient Sena kings of Bengal with miracles, Sufis are given the right to clear forests and settle Muslims. Neither this narrative nor the shrill claims of the aristocracy are “true”—both simply used the past to comment on their present.

In 1988, Bangladesh officially declared it would follow an “Islamic way of life” through a Constitutional amendment. In the decades after, a colonial-era law was to target atheists, rationalists, Hindus, and members of other religions for “hurting religious sentiments”. In the aftermath of the political revolution in 2024, Hindu minorities are being targeted. Whether this is politically motivated bigotry, only time will tell. The truth is that like India itself, in Bangladesh there is no historical case to separate Hinduism and Islam: it is the intertwining of religions, not their conflict, that has shaped the subcontinent.

Anirudh Kanisetti is a public historian. He is the author of Lords of the Deccan, a new history of medieval South India, and hosts the Echoes of India and Yuddha podcasts. He tweets @AKanisetti. Views are personal.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)