Participants in the Mahabharata war; attendees of the sacrifices of Dasaratha, father of Rama; descendants of the moon god—and simultaneously devotees of ancient hill gods; rivals of Vaishnavite Manipur; and possessors of a complex relationship with the Bengal Sultanate. This is a brief exploration of the Manikya dynasty of Tripura, which ruled the region for nearly 500 years. Their story weaves a rich tapestry of state formation, religious interactions, the pull between mountain and river valley, and global trade.

The shadow of the Bengal Sultanate

As we saw in the previous edition of Thinking Medieval, India’s Northeast—so often divided along ethnic lines and constrained by a colonial-era border—is, in fact, one of Asia’s great crossroads, linked to mountain systems that form the very spine of the continent. These mountain systems, counterintuitively, acted as a trade highway. Goods and ideas circulated through them at enormous scale, connecting apparently-isolated mountain strongholds to vast global networks. A striking example of this comes from cowrie shells, studied by Mizo historian Joy Pachuau in Flows and Frictions in Trans-Himalayan Spaces: Histories of Networking and Border Crossing. Used as petty currency for centuries, in some cases as late as the 1700s, these shells originated as far away as the Maldives and Philippines before being drawn into networks in Bengal, Arakan, and the associated mountainous regions.

It was within this diverse world that the state of Tripura emerged in the 15th century. The Rajamala, a Tripuri court chronicle from that era, suggests a push-and-pull between the peoples of the hills and those of the Ganga-Brahmaputra Delta, over whom the thriving cultural and economic world of the Bengal Sultanate cast a long shadow. The Sultanate underwent a brief crisis during this time, when a local magnate, Raja Ganesh, became its de facto ruler before passing the throne to his son Jalaluddin Muhammad Shah, the first Bengali to rule as a Muslim Sultan.

After enlisting Ming Chinese diplomacy to fend off his western neighbour, Jaunpur, Jalaluddin extended Bengali power east to Arakan. It was through this that they came into contact with the chiefs of Tripura, who were just beginning to expand from the hills to the plains. The Tripuris were either subjugated or managed to drive off the Bengalis—the sources are conflicting. The Rajamala claims that a Sultanate army was defeated by a Tripuri queen after feasting her warriors on buffalo and goat meat. What is clear is that by 1464, the Tripuris felt confident enough to issue their first coinage.

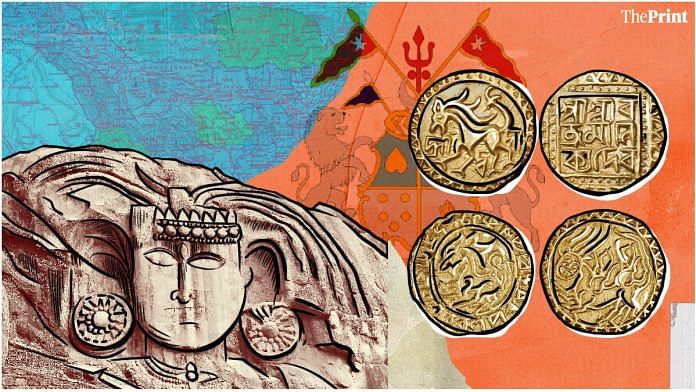

Coins, as seen in different places and periods of South Asian history, were small, portable pieces of propaganda. The very first Tripuri coin was a close imitation of those of Sultan Jalaluddin, with elegant line work depicting a lion. (Or, should I say, elegant lion work). This lion was both an Arabic motif, and linked to the Shakti worship of his father, Raja Ganesh. The goddess Durga is, after all, believed to ride a lion. It seems that in this diverse economic world, Bengal Sultanate coinage was considered the most reliable standard of value, leading the Tripuris to copy it so that their coinage could spread into the same networks.

However, the king who issued this—Ratna Manikya, a Sanskritic regnal name—is also depicted by the Rajamala as having obtained his throne and the title “Manikya” from the Bengal Sultan, as well as an infusion of Bengali and Persian speakers for his new state. On the other side of South Asia, at the same time, the first kings of Vijayanagara in the Southern Deccan also claimed legitimacy as supposed wards of the Sultan of Delhi. Both of these were probably little more than political posturing, but they still reveal that in the late medieval world, Turko-Persian rulers were considered a legitimate, wealthy, and powerful source of authority.

Also read: Manipur’s imperial moment—When King Gharib Nawaz spread Hinduism, conquered Burma

Between Hindu and hill god

Tripura had a complex relationship with the Bengal Sultanate, to be sure, but it also had a complex relationship with Hinduism. As historian Richard M. Eaton writes in The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier: 1204-1760, it was through the 1500s and 1600s that much of the Ganga-Brahmaputra delta was finally brought under cultivation; as local pastoralists became landed peasants, they converted to Islam. But even as the agrarian and Persianate frontier moved east, so too did Hinduism—to be precise, Bengali or Gaudiya Vaishnavism. In the 1700s, for example, the Manipuri king Gharib Nawaz converted to Gaudiya Vaishnavism, with spectacular consequences.

The Tripura region had already interacted with the Hindu gods, especially Shiva and various goddesses, as early as the 8th century CE. This is indicated by the stone carvings of Unakoti, today called “The Angkor Wat of the Northeast”, in a strained comparison that does neither of these sites justice. But the nature gods of the land continued to be worshipped. When the Tripuri state was established in the 15th century, its ruling Manikya dynasty instituted a Hinduised royal cult of the nature gods, now called the “Fourteen Divinities”, and identified with mainstream deities such as Vishnu, Saraswati, and Shiva. Interestingly, they were worshipped not as anthropomorphic idols but as busts—relatively rare in Hinduism but common in the older religious traditions of the region.

The Rajamala claims that this was an ancient practice instituted by an ancestor of the Manikyas, in order to grant the stamp of tradition to a relatively new practice. It is also in this context that we should see its claims that Tripuri kings were descended from the moon, fought in the Mahabharata war and witnessed the events of the Ramayana. Some have been too eager to take these claims literally to prove that India’s Northeast was always Hindu, a tragic oversimplification that does no justice to the region’s early modern religious history. Rather, we should ask why it was so important for Tripuris to claim that their royal line was so ancient: it was a way for them to legitimise their authority, distinguish themselves from other chiefs, and bridge the Sanskritic and local worlds, as historian Deepayan Chakraborty argues in Legitimisation Process in Tripuri State Formation: Accommodating Sanskritization & Primordial Culture.

Nevertheless, the Hinduism of the 15th and 16th century Manikya dynasty was very different from the religion we know today. When describing the career of Dhanya Manikya at the beginning of the 1500s, the Rajamala, in tremendously entertaining fashion, describes how unearthed dragons helped his armies scale fort walls; how fierce yoginis caused floods to wash away Bengali armies; how he beheaded his rivals in formal audience not once but twice. All of these might seem “Hindu” enough. But then, when describing the material culture of Dhanya Manikya’s expanding kingdom, which included Chittagong and various hill forts of Kuki peoples, it mentions elephants’ tusks, yaks, goats, gong-bells, plates, jugs and spittoons made of pewter, and colourful fabrics of red, black and white, copper bangles, cedar wood, spears, swords, and ponies. It also describes the sacrifice of a young Dalit man to create a horrible sound that scared off a Bengali army, and claims that the king reduced human sacrifice from dozens a year to one person every three years. Dhanya Manikya is also praised, from the viewpoint of the Rajamala’s Brahmin authors, for his patronage of Brahmins and construction of temples.

Even from this impressionistic sketch, it should be clear that in Tripura, the Sanskritic culture was a veneer over a vibrant, cosmopolitan Northeastern world that we are all too eager to dismiss today as “tribal” or “violent”. Religion has always been a tremendous force when deployed by the state, and the Manikyas of Tripura—suspended between Bengal and Burma, Hinduism and nature-deities—are well worth remembering for this.

Anirudh Kanisetti is a public historian. He is the author of Lords of the Deccan, a new history of medieval South India, and hosts the Echoes of India and Yuddha podcasts. He tweets @AKanisetti. Views are personal.

This article is a part of the ‘Thinking Medieval‘ series that takes a deep dive into India’s medieval culture, politics, and history.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)