It is high time that we—however briefly—attempt to understand the rich, complex history of Manipur. “Stories about Manipur in the Indian media were almost always about violence,” wrote the Burmese diplomat Thant Myint-U in 2012. Eleven years on, it seems that nothing has changed. In this article, I instead want to look to Manipur’s past, specifically its brief, dazzling imperial moment, when it humbled the mightiest state in Southeast Asia.

Migrations in the mountains

While it is all too common to perceive Manipur as a distant frontier of the Ganga-Brahmaputra river valley, the region’s primary geographical concern for much of its history was not the vast North Indian plains to its west but the much closer Irrawaddy river valley to its east.

Although we often think of history as centred on the river valleys, this is not the most intuitive way of understanding the region today in India’s far east. It is possible to instead see it as a sub-system of the Southeast Asian Massif, one of the world’s most extensive and interlinked mountainous systems. Despite its forbidding terrain, the Massif acts as an elevated highway, connecting most of Eastern Asia’s river valleys and population centres. It spans across ten modern nation-states, from Vietnam to India. Historically, the Massif was inhabited by diverse cultures, linguistic groups, and ethnicities. Their migrations and trade routes impacted river valleys from the Ganga to the Mekong and Yangtze. However, due to the Massif’s generally poor soils and low population density, river valley states found it difficult to penetrate and control the region. This situation changed only with the extensive deployment of gunpowder and telegram technology in the 19th century.

While river valley states struggled to impose their authority over the Massif, its own people were adept at forming their own states. Manipur was an important state in the region. Situated in an oval basin watered by several smaller rivers, it attracted a staggering number of communities, including speakers of Sino-Tibetan and Austro-Asiatic languages. It was an important node in trade networks connecting Tibet and Yunnan (Southwest China) to the Irrawaddy and Brahmaputra river valleys, especially in the trade of sturdy mountain ponies. Many of these ponies found their way into the wars of medieval peninsular India.

One of the most prominent Sino-Tibetan languages in the region is Meitei, currently one of India’s 22 official languages—very much on par with Hindi, Tamil, Telugu, and Kannada. Manipuri historian Saroj Nalini Arambam Paratt writes that the Meitei were once a confederacy of seven clans, each with their own divinity (The Court Chronicle of the Kings of Manipur: The Cheitharon Kumpapa). The confederacy gradually came under the domination of the Meitei Ningthouja clan and thus obtained the name. It was Kangleipak, the Meitei state, that would lay the foundations for present-day Manipur.

Also read: Medieval Indian engineers in the 7th century built robots. Powered by water and clockwork

Manipur’s imperial moment

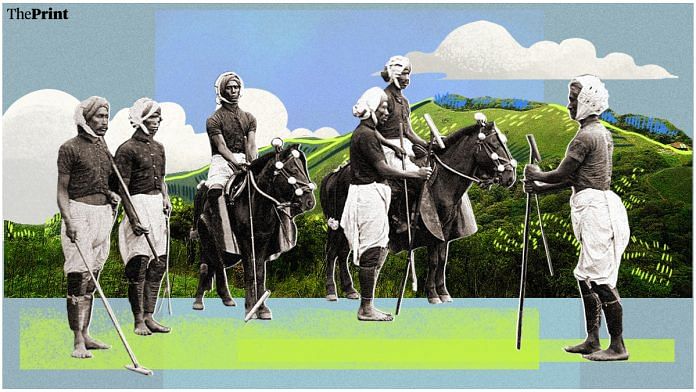

In the 15th century, catalysed by state formation by the Shan peoples of Upper Burma, the Kangleipak kingdom began to centralise. Inspired by a meeting with a Pong king from Burma, the Meitei king Kyampa ordered the creation of a “national chronicle” called the Cheitharon Kumpapa, which recorded events from the perspective of the Meitei court. This chronicle reveals a rich, colourful, cultural world: one where rivers were harnessed for irrigation, where the people were warlike and loved sport, including boat races and polo. It is also surprisingly detailed. For example, an entry from 1709 CE reads, rather tersely: “21 of the month of Lamta [February/March] Friday, a memorial mound was erected for Ningthem Charairongpa [the previous king]. The wind was fierce on that day. Many trees and bamboos were uprooted. Two people who were carrying cooked rice were injured by the falling trees.”

Something even more memorable happened that year: the accession of King Mayemba or Pamheiba. Threatened by the expansion of the Burmese empire of Taungoo—the most powerful gunpowder empire in Southeast Asia—Pamheiba sought to centralise Kangleipak. To do so, he relied on an ancient South Asian legitimisation mechanism: the patronage of Hinduism. Gopal Das, a Gaudiya Vaishnava guru from Bengal, formally initiated the king and a few courtiers in 1717. Interestingly, the king later came to be known as Gharib Nawaz: one of the titles of the famous Khwaja Moinuddin Chisti. Whether this was because he was charitable, because veneration of the Khwaja spread alongside Vaishnavism, or simply because Pamheiba sought to depict himself as a Persianised ruler, is unclear.

In the previous year, the Burmese had demanded a bride from Kangleipak. In 1717, under the guise of a marriage party, Gharib Nawaz’s troops surprised and kidnapped the Burmese groom and his attendants. They also burned several villages under Burmese control and took numerous prisoners. This initiated a pattern of annual attacks and raids between Kangleipak and Burma, allowing Gharib Nawaz to acquire guns, horses, and treasure, which were used to subdue tribes in the neighbouring hills. All the while, he attempted to centralise his state, ordering the construction of vast irrigation works through corvee labour. In 1738, after fending off attacks from both Burma and Tripura, the fearsome Manipuri cavalry sacked and burned Buddhist sacred sites on the outskirts of Ava (present-day Inwa), the ancient Burmese capital. The Maharaja returned with a tremendous loot. It was the apogee of Manipuri power.

In 1726, Gharib Nawaz performed a controversial ritual in which representations of seven lais—clan divinities—were brought to a sacred grove and smashed, after which they were buried under a newly-built Hindu temple. A palace and several houses were burned, and new currency was introduced. The king’s motivations behind these actions remain unclear. Saroj Paratt, the Manipuri historian, describes it as an “attempt at the complete destruction of anything pre-Hindu by force” (Garib Niwaz: Wars and Religious Policy in 18th Century Manipur). She also provides evidence of the persecution of beef-eaters, the invitation of Bengali Brahmins and mendicants, and clashes between the Gaudiya Vaishnavism of the court and other sects. Burmese legends claim that Gharib Nawaz’s attacks on pagodas were motivated by religious fanaticism following sermons to his troops by his guru, Gopal Das. Gangmumei Kamei, another Manipuri historian, also supports the view that Gharib Nawaz was a zealot (History of Manipur: Pre-colonial Period). However, while personal belief may have played a role, it cannot be separated from both the royal and religious desire for power, a dynamic seen in similar events elsewhere in South Asia.

It is also unlikely that Gharib Nawaz’s state possessed the capacity to enforce such measures on a large scale. He did construct temples in various locations, including the hilly regions, possibly to act as centres of integration. And in 1738 and 1739, hundreds of Kangleipak subjects took the sacred thread. The Cheitharon Kumpapa claims that “most of the people in the country were made to take the sacred thread”, but it also mentions that “many who were told not to take the sacred thread did take it” the following year. As a court chronicle, it is not an unbiased source. It is possible that the Maharaja attempted to use conversion as a means to woo and control his aristocrats while elevating his own status. His Hindu clergy also adopted local customs, such as elephant-hunting. However, both Gharib Nawaz and his guru were assassinated after the king was forced to abdicate and leave Imphal in disgrace in 1751. The deceased Maharaja was subsequently venerated as a lai, although lai worship itself was gradually assimilated into Manipuri Hinduism.

By the 1800s, the Burmese devastated Kangleipak, leaving it as an easy target for the British. Manipur’s imperial moment was over. But the rich history of its 18th century reminds us not to take the states of India’s far east for granted. The assimilation of Sino-Tibetans into Gaudiya Vaishnavism, the burning of Burmese Buddhist stupas — these elements fit nowhere in the binary narratives that we are accustomed to. Through their geography and history, India’s northeastern states challenge many of our assumptions about South Asia’s past, and they deserve to be given as much importance as the Deccan or the Gangetic Plains.

Anirudh Kanisetti is a public historian. He is the author of Lords of the Deccan, a new history of medieval South India, and hosts the Echoes of India and Yuddha podcasts. He tweets @AKanisetti. Views are personal.

This article is a part of the ‘Thinking Medieval‘ series that takes a deep dive into India’s medieval culture, politics, and history.

(Edited by Prashant)