The overwhelming victory of the Bharatiya Janata Party in two consecutive Lok Sabha elections has heralded India into a new era. Some observers describe this emerging pattern of competition as the second phase of one-party dominance, the first one referring to the period of Congress domination over national and state politics in the 1950s and 1960s.

The current configuration, however, is of a slightly different nature because of how it is setting up a new political culture – not just by co-opting civil society groups and local elites but also its opponents.

The fundamental characteristic of a single dominant party is that it is “centripetal”, meaning it draws all elements of civil society into its ambit. The politics is structured in a way that allows the dominant party’s organisation to penetrate into all elements of society, which manifests itself in the ideological centrality and electoral superiority of the party.

In the Indian context, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has sought to centralise political power in its national unit, through the charismatic authority of Narendra Modi.

The party also has developed a significant resource advantage in terms of campaign finance and driving media narrative. This has coincided with the BJP-led government unabashedly promoting an ideological agenda that will re-define majority-minority relations on the ground, re-ignite the debate on citizenship norms, dramatically alter the federal balance of power, and construct a new political culture.

Also read: The new voters for Modi’s BJP are poorer, more majoritarian but not as religious

Ideological centrality

The BJP within the six months of coming back to power has pushed legislations to realise some of its long-standing projects such as the abrogation of Jammu and Kashmir’s special status through Article 370, the construction of a Ram temple in Ayodhya, the implementation of National Register of Citizens (NRC) and of the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA). Despite serious setbacks in recent state elections, these policy decisions retain a high level of popular support, to the point that even the opposition seems to be mirroring its ideas and tactics.

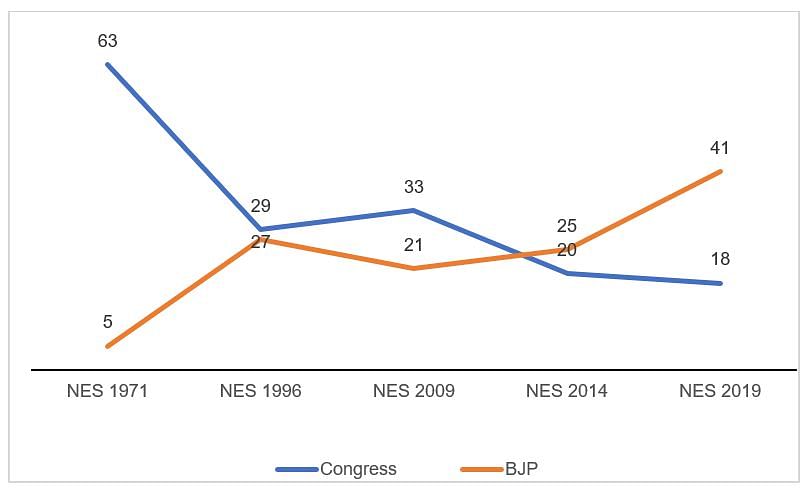

Data suggests that a larger proportion of citizens are now identifying with the BJP. The Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS)-Lokniti surveys have asked respondents to identify which political party, if any, they feel close to. The proportion of respondents who identify with any political party has mostly remained the same across the five decades beginning 1970 – approximately one-third of the Indian electorate. However, there has been a sea-change in their partisan preference (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Identification with the BJP has increased

In 1971, an overwhelming number of those who felt close to a party picked the Congress (almost 70 per cent). By 1996, the BJP and the Congress had similar levels of support from partisans (those who feel close to any party), about 27 per cent each. In 2019, the BJP had more than twice as many partisans identifying with it (41 per cent) than the Congress (18 per cent). As an analytical concept, the importance of party identification lies in the fact that it is relatively exogenous to the more specific short-term factors and provides a stable basis of support for a party. They make for a party’s core support base and give it a mainstay on which to mobilise new voters.

Also read: Four reasons why BJP is losing to Congress and regional parties in assembly elections

Disjuncture between state and national elections

One of the more curious aspects of the current party system is that the electoral dominance at the national level does not extend to the state level. If anything, the recent trend has been for the BJP to lose the election, or at least a significant vote share, in states in which it performed well in the national election. In Delhi, Haryana, and Jharkhand assembly elections (all of which took place within a year of the BJP’s 2019 Lok Sabha election triumph), the BJP lost at least 18 percentage points in vote share as compared to its national performance.

Nowhere is this disjuncture more evident than the electoral behavior of Odisha — which held its assembly election simultaneously with the national election. This means that voters cast two ballots – for state- and national-level leaders. Of Odisha’s 21 Lok Sabha (national) seats, the BJP won eight with an average seat-wise vote share of 38 per cent in 2019. Going by its 33 per cent average seat-wise vote share in the assembly (state) election, the BJP would have won none of Odisha’s 21 Lok Sabha seats.

But this too is a manifestation of the centralisation of power as well as campaign resources in the BJP’s national unit. In a bid to make sure that Narendra Modi remains its most popular leader, and reduce factional feuds in the party, the current avatar of the BJP has weakened the position of its own regional leaders. This state of affairs simultaneously puts the BJP at an electoral advantage in national elections and at a disadvantage in state elections. If the BJP continues to remain dominant nationally, ascribing more power to the central leadership is likely to weaken India’s federal bargain.

Also read: A chaiwala is PM, but it’s the cartel of power elites that calls the shots in India

The changing social bases of politics

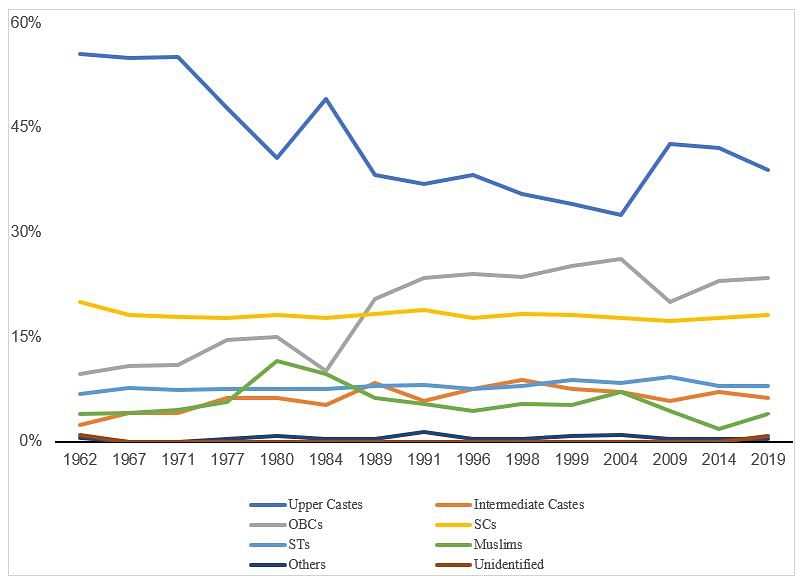

Since 2014, the rise of the BJP has been associated with an upsurge of representation of traditional elite groups, namely the upper castes, across the Hindi belt. In several important states such as Uttar Pradesh or Bihar, upper caste representation has gone back to pre-Mandal levels, around 40 per cent of the seats and between 45-50 per cent of all the BJP’s elected representatives. Other Backward Classes (OBC) representation, which rose significantly during the 1990s, has either plateaued or decreased in most north Indian states, around 23 per cent. Most chief ministers appointed by the BJP since 2014 belong to the upper castes, who are also over-represented in regional cabinets.

The data, however, indicates that the upsurge of traditional elite representation precedes the rise of the BJP (Figure 2). In the Hindi belt, upper caste representation in the Lok Sabha jumped by 10 per cent between 2004 and 2009, to 43 per cent of all MPs from those states. An examination of the caste composition of all major parties shows that, by and large, upper castes have regained their lost political strength in elected assemblies by virtue of being co-opted by most parties – if not all – including by the regional parties that initially rose in opposition to the traditional social and political order.

Figure 2: Caste and community representation in the Hindi Belt (1962-2019)

Over the past few decades, parties that used to mobilise a core electorate defined narrowly in specific caste terms have been incentivised to build up more inclusive platforms and seek to appeal to a larger array of groups, by offering them representation. This has essentially meant that most parties tend to recruit their candidates from the same sociological pool of local elites. The BJP offers much continuity in that regard and has succeeded in combining the elite co-optation strategy that used to work for its adversaries with its encompassing Hindutva project. By reconciliating Mandal and Mandir, the BJP has, in effect, enhanced the elitist character of India’s political class.

In the past two decades, Indian politics has been undergoing a significant transition, which includes rapid changes in the demographic composition of Indian electorate (for example, more middle class) and voters (for example, more women turning out), alongside advancement in information and communication technology, which meant a larger population now consumes mass media.

The full impacts of these changes are yet to be known. Nonetheless, recruitment patterns within political parties, nomination criteria, and campaign strategies, among other indicators of electoral contests are undergoing a visible reorganization. This rearrangement of forces, along with the BJP as a system-defining party, is likely to generate long-lasting social and political transformations in Indian society.

Rahul Verma is a Fellow at the Centre for Policy Research (CPR), New Delhi. Neelanjan Sircar and Gilles Vernier are both Senior Visiting Fellow at CPR as well as Assistant Professor of Political Science at Ashoka University.

This series of articles is a curtain-raiser to the CPR Dialogues, an international conference on public policy, to be hosted by the Centre for Policy Research on 2 and 3 March in New Delhi. ThePrint.in is the digital partner for the conference. Read all the articles in the series here.

It appears that your whole article suggests that the political tricks and maneuvers are the only things which leads the course on which the Indian political scenario evolves, it seems according to this article that that policies of the government and its success or failure have no say in voters dynamics and party politics of the country which i assume is not the case.

UP and Bihar are the worst of 29 states and by and large majority of Indians are ashamed of them .It is beyond me why you select them for everything, as a baseline or-placebo. You scre your conclusions.

The very fact that people from various segments, including opponents, are joining the BJP, should be a source of both joy and fear for the liberals. Joy, because BJP’s ideology may be diluted if opponents join it. Fear, because BJP will have more voters.