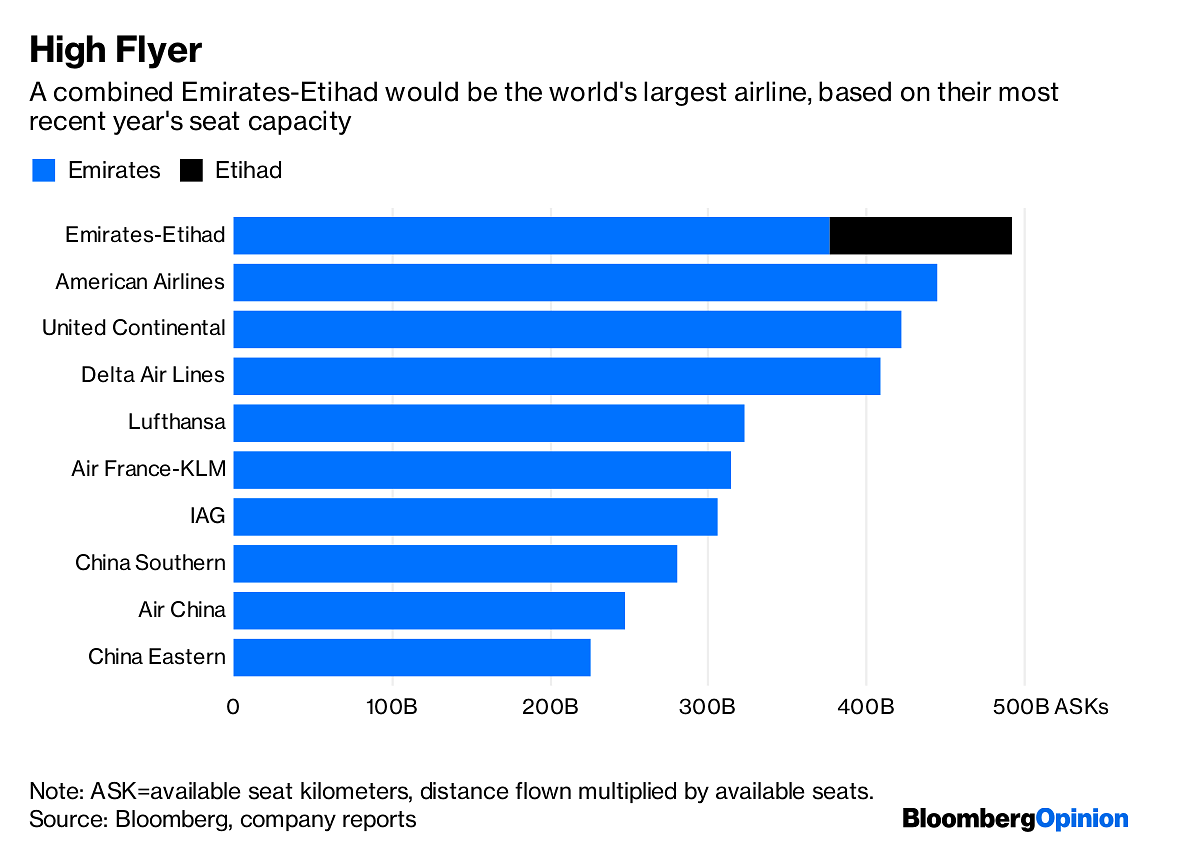

What Emirates will gain in terms of scale by acquiring Etihad it will lose in terms of operational freedom.

A takeover by Emirates of Etihad Airways PJSC is the megadeal that has to happen in the global airline industry. At the same time, it’s a poisoned chalice for the suitor that may hobble its growth plans for a generation.

The two carriers are in preliminary talks over a deal, people familiar with the matter told Layan Odeh, Dinesh Nair and Benjamin Katz of Bloomberg News on Thursday. Any discussions may be protracted because combining these two airlines will be as difficult and risky as getting hedgehogs to mate.

While countries the size of China and the U.S. have domestic markets large enough to sustain multiple global hub carriers, the United Arab Emirates is a much smaller beast, with a population of just 9.4 million. Trying to establish not one, but two world-connecting airlines there (just down the road from a third global hub airline in Qatar, population 2.6 million) is a bit like trying to do the same thing in Hong Kong or Singapore.

Sibling rivalry

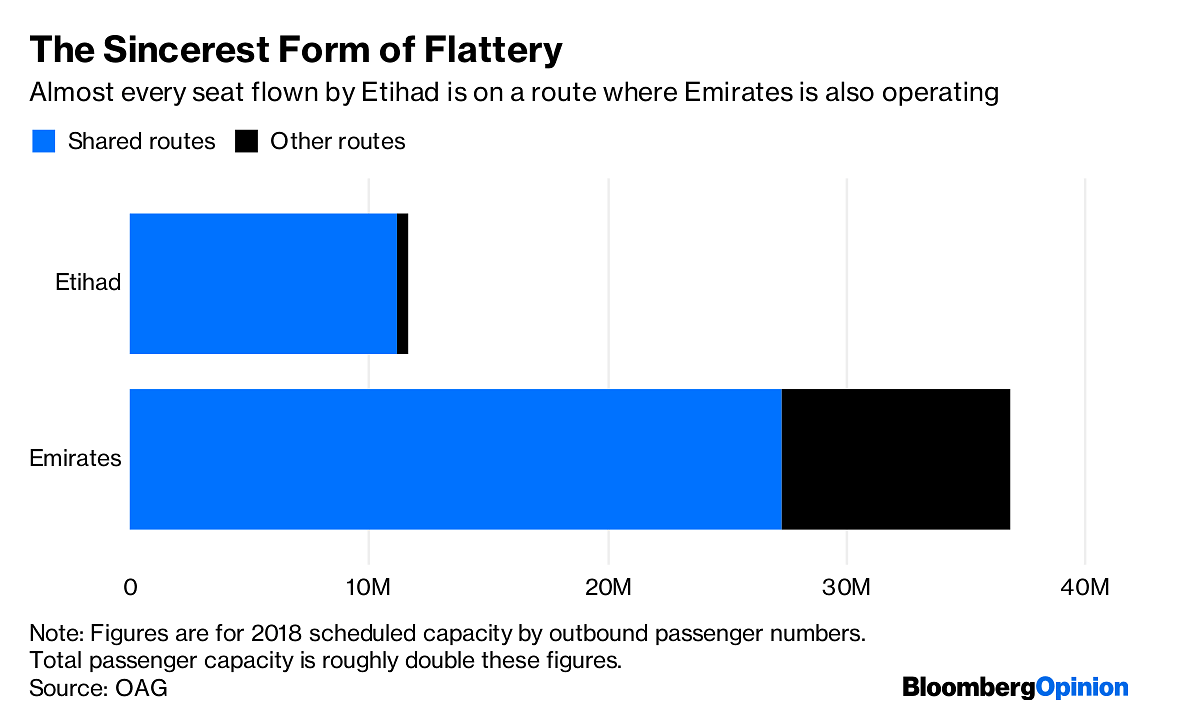

The two carriers are in many ways duplicates. Of Etihad’s 88 passenger destinations, all but 11 are also served by Emirates — and that group of destinations is a distinctly third-tier bunch consisting of Amritsar, Astana, Chengdu, Edinburgh, Jaipur, Kathmandu, Kozhikode, Minsk, Nagoya, Rabat and Riga.

Analysis of data from OAG Aviation Worldwide Ltd., an analytics consultancy, suggests that routes flown by both airlines account for about 96 per cent of Etihad’s total outbound capacity this year, and 74 per cent at Emirates.

The overlap is certain to be closely scrutinized by antitrust authorities, who typically view airline mergers in terms of a myriad city-pairs that each pose their own competition issues.

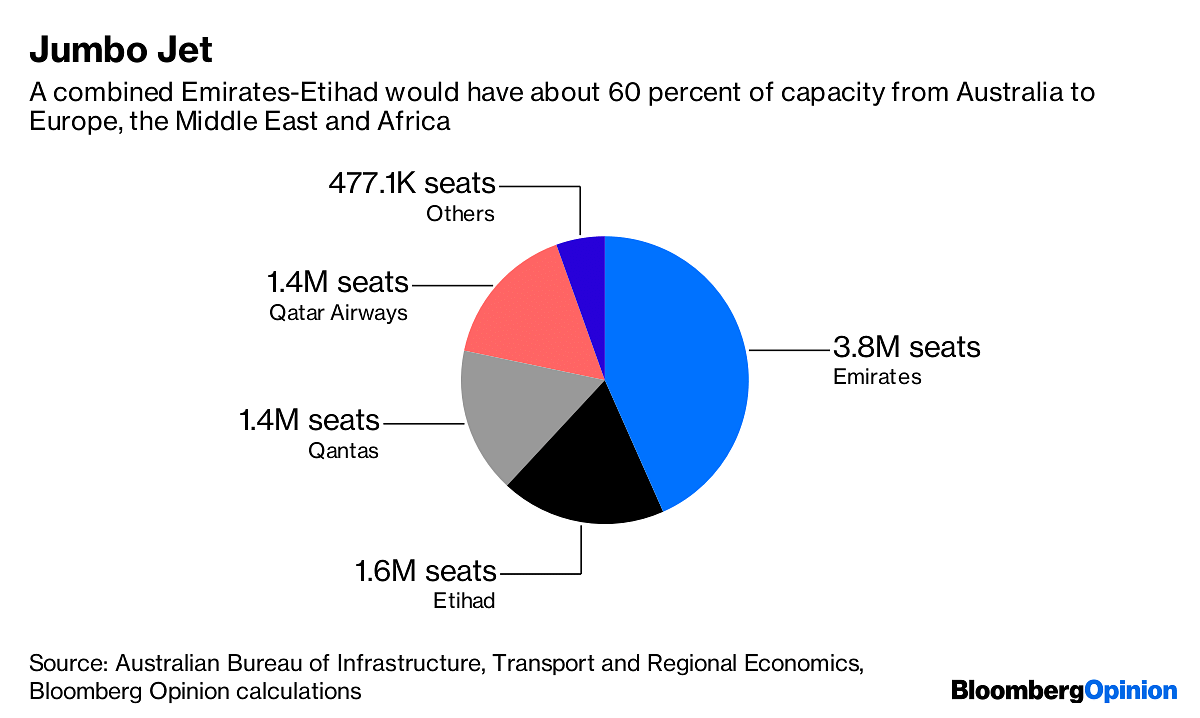

For many destinations in the Middle East, India and Australia, Emirates is already dominant: On routes between Australia and Europe, Africa and the Middle East, for instance, it had a 43 per cent share of passenger capacity over the past year. Adding Etihad to that total is likely to be unacceptable without the carriers agreeing to drop routes or slots at major hubs.

In some places that could be a blessing. Being based in the same country, the sibling rivalry between Emirates’s base of Dubai and Etihad’s home turf in neighboring Abu Dhabi has been fierce. Any services that antitrust authorities force the parties to give up might help tighten the market and support ticket prices.

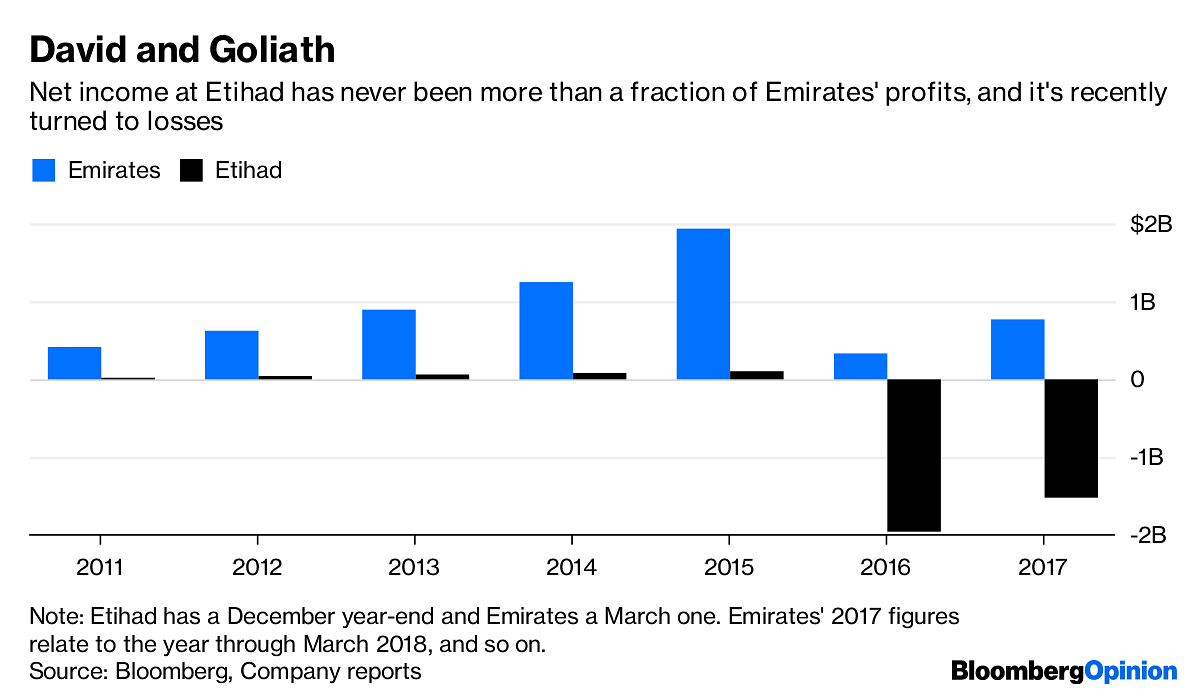

In other ways, though, it’s a minefield. Tim Clark, Emirates’s president, has grown used to operating the company with a ruthlessly free hand, a secret to its success in recent decades. The sensible thing to do would be to effectively close Etihad down: Cherry-pick its best aircraft, employees and routes; bolt them onto Emirates’s much larger business; and dispose of the remainder. But the internecine politics of the U.A.E. makes that impossible.

A problem with the model

Both airlines are essentially state enterprises owned by the royal families of their respective emirates. While Dubai has always been the leader in terms of entrepreneurial zeal — one reason Emirates was established in the first place — Abu Dhabi has about 90 per cent of the oil reserves that keep the whole show on the road for the U.A.E. When Dubai’s debt-fueled growth path spiraled out of control during the 2008 financial crisis, it was Abu Dhabi that stepped in with $20 billion of bailout money, a sum that’s since been rolled over at below-market rates.

That means that the sensible, radical path isn’t really an option. The combined group will somehow have to maintain service levels to Abu Dhabi to please the Al Nahyan family, the final arbiter of economic and political power in the U.A.E., while doing its best to build up its core hub in Dubai.

It’s not clear such a model could work. The core of a hub carrier is the ease of the transfer experience and the wealth of connectivity it can offer to passengers. That’s hard enough to manage under a single roof. Doing it with two different sites an hour apart by road seems impossible, especially as it competes with rivals connecting through sparkling new Asian airports or flying nonstop on new long-haul jets.

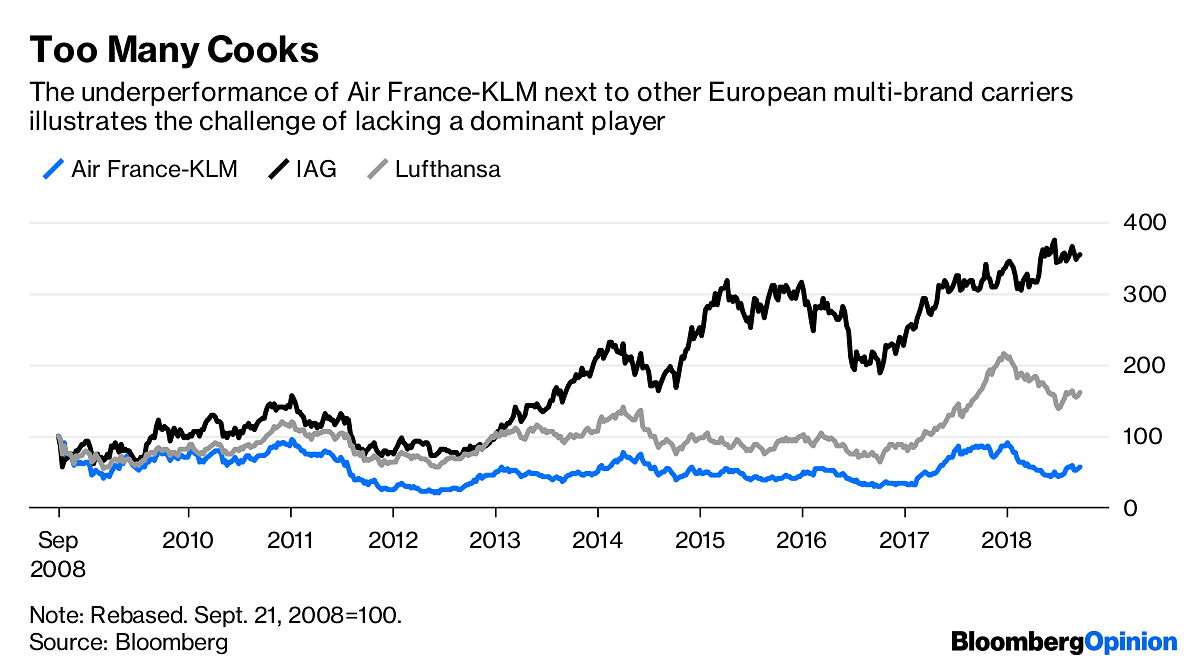

There are potential solutions out there. Perhaps the route network can be split such that all but a handful of low-margin passengers transit at one site or the other. Air France-KLM has managed to survive, however awkwardly, as a twin-hub carrier; though the experience of the much more lopsided Deutsche Lufthansa AG and International Consolidated Airlines Group SA demonstrates the advantage of picking one dominant hub.

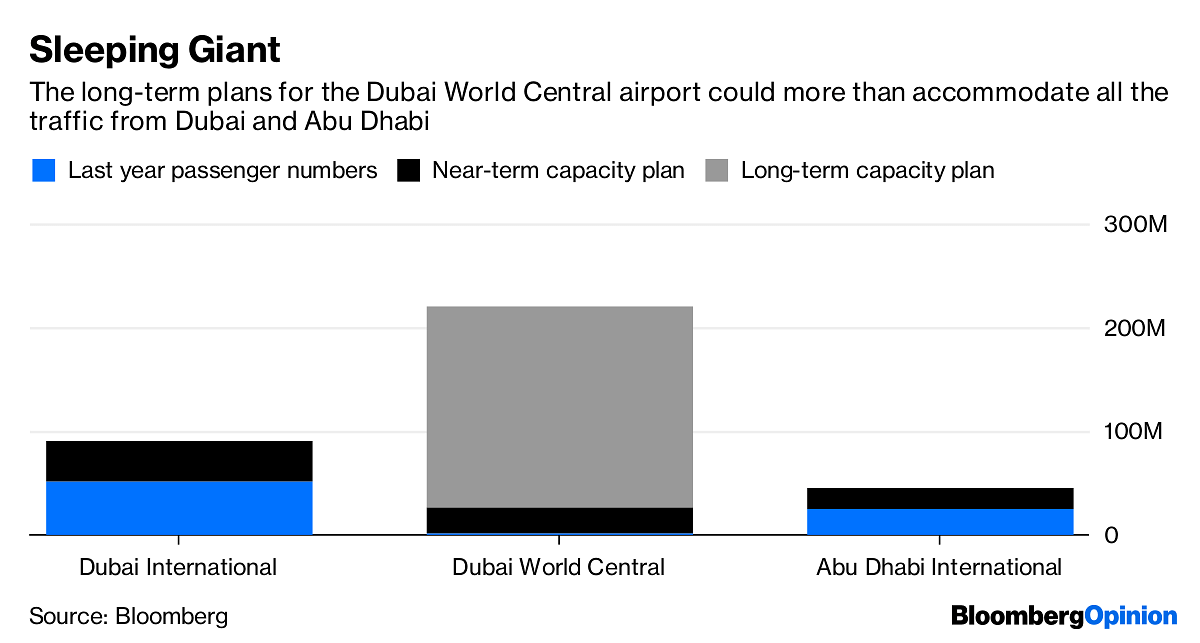

Better still, both airlines could move to the massive future Dubai World Central airport, which sits close to the border between the two emirates — though that option would leave Abu Dhabi’s Midfield terminal looking like an expensive folly before it’s even opened.

Either way, what Emirates gains in terms of scale it will lose in operational freedom. Etihad has never had a very clear reason to exist, beyond jealousy of Emirates’s success. In its current loss-making and weakened state, it may be about to deliver the most devastating blow against its sibling carrier yet. – Bloomberg