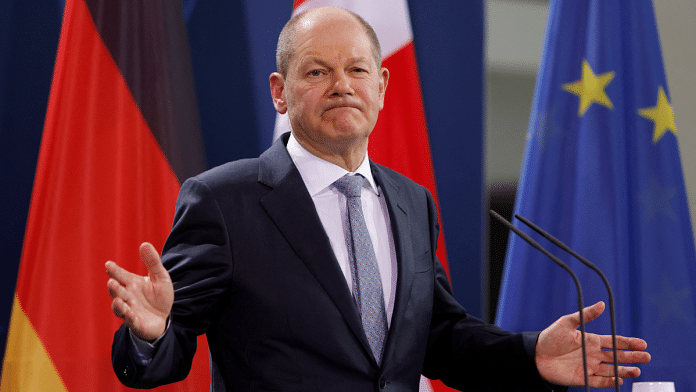

Germany would still like to believe that it can influence China to persuade Russia for a de-escalation in the Ukraine war. At least this was Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s European pitch to balance the otherwise emphatic business imperative that took him to Beijing recently, almost a year after he last visited China in November 2022.

On his three-day trip that started on 13 April, Scholz met Chinese President Xi Jinping and Premier Li Qiang and held a press conference with the German-Chinese economic committee. He also visited the southwestern industrial city Chongqing and the economic centre Shanghai.

In July 2023, the German parliament, Bundestag, came up with its first China strategy, signalling the gravity of Germany’s efforts at de-risking from China in line with the larger European Union (EU) approach. However, watered down from the start, its objectives became more diffused and less convincing as German investments in China reached a record high toward the end of 2023, at a time when Europe’s investments reduced drastically. This trend has very well continued in 2024, as investment data from February has yet again shown a record high.

In the same period, Europe has been aghast by Beijing’s nonchalant endeavours to up Moscow’s war efforts with dual-use technology and other military support against Ukraine. According to US intelligence reports, China and Russia are working together inside Russian territory to produce more drones. That said, instead of giving this strategic concern an equal space in his latest travel agenda, the economic imperatives dominated Scholz’s engagements, solemn witness to China being the most important trading partner to Germany for the eighth year in a row. It also shows how complicated de-risking is from China at a time when Chinese EVs like Nio are outcompeting German ones.

Also read: Europe is Trump-proofing Ukraine on 7 counts. NATO is latest to join the pursuit

Electric cars and anti-dumping

Both the United States and EU have been cautioning the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to check the government backing given to EVs despite their economic losses, a trend epitomised by Nio. In 2023, the EU launched an investigation into whether or not electric car manufacturers in China thrive on government subsidies, to make a case for imposing tariffs on electric car imports from China that had surged by 850 per cent since 2020. It is true that fears of retaliation would harm European car makers’ interests that are deeply tied with Chinese counterparts. Beijing calling this “naked protectionism” by the EU doesn’t bode well in the West when the very reason stems from China’s unjustified backing to the sector that has led to overproduction at cheaper costs.

It is not all about subsidies, though. At the heart of this tension is also the edge China has in technical innovation battery technology and other critical aspects of the EV supply chain, which is more automated in Beijing than anywhere else in the world.

All this is leading Europeans to double down on their innovation drive, but the effects will take time to show. Until then, we should expect more such visits such as Scholz’s to China, aimed to protect the interests of the German businesses that are far more entwined with Chinese than other Europeans.

Also read: Ukraine foreign minister’s visit to India opens door for Delhi to shape post-war Europe

If you can’t beat them, join them

There are two reasons why German business interests remain so entwined with Chinese. One, the numbers: Almost 5,000 German companies operate in China. Two, some have struck fresh partnerships even when Brussels has strived to de-risk from Beijing. Volkswagen, for instance, has bought a 4.99 per cent stake in Xpeng, a Chinese car start-up and paid it $700 million in 2023.

Germany’s call for de-risking from China despite its reliance on the latter and its China strategy has become repeatedly evident. The stories of German companies joining Chinese ones in areas where they cannot compete come on top of developments like chemical giant BASF moving production bases to China, unable to manage the rising energy costs after the war in Ukraine, which, ironically, is stretching on because of Beijing’s support. The same inconsistency appears when German investments in China keep growing despite screening of investments touted as an objective of de-risking both by the EU and Germany.

Scholz delivered the same message from Europe that the US conveyed through Secretary of the Treasury Janet Yellen during her recent trip to Beijing. She raised concerns over anti-dumping and cheaper production due to unfair subsidies. It did appear that Scholz took a similar position to keep the US appeased too.

It is assessed that by 2025, the US will overtake China as Germany’s topmost trading partner if the current trends continue. The US’ current economic performance is very much attributable to German exports.

China, on its part, has been de-risking from the US and the EU too. Its exports to Western markets are declining, and to India, Russia, Latin America are rising. Therefore, to some extent, the more Chinese and Western markets untangle, the lesser would be the incentive for the former to rectify its unfair trade practices. But in reality, it remains a farfetched proposition to assume that EU probes into EV subsidies and the resultant fall in imports in early 2024 do not impact China even when its exports of solar panels, EVs, and lithium ion batteries to regions like Latin America are booming. The overall trade between the West and China is a key driver for the latter as it is for the former. It will be interesting to see which side actually de-risks more from the other at what cost and how it impacts geopolitics, particularly China’s backing of Russia. For now, the status of China as a partner, competitor, and systemic rival to the West will continue to shape the geoeconomics of our times.

As pleasant and matter-of-factly as Scholz appeared at the press conference, he offered only silence when asked about Xi’s response to Beijing’s rising support to Russia. Perhaps the only key takeaway on the security situation in Europe, where the two sides had more clarity, was against nuclear threats and Xi’s promise to ‘back’ an upcoming peace conference in Switzerland.

Also read: EU’s real problem isn’t war fatigue. It lacks a grand strategy

Scholz’s domestic compulsions

One of the most prominent China hawks in Scholz’s coalition today is the Greens leader Annalena Baerbock, the German foreign minister. She and her party seem out of sync with the needs of German industries if a transition to renewables needs to be made while simultaneously supporting Ukraine and de-risking from China. The Greens symbolise what Rob Henderson calls “luxury beliefs of the elites”. Despite an impressive diversification away from Russian natural gas supplies at an incredible pace since the war started, it is a lack of a vision and modus vivendi on managing the biggest questions for the country’s economic survival that has led to a cacophony of sorts in German debates.

To make matters worse, the Scholz coalition has also been facing a budget crisis back home. In November 2023, the Constitutional Court, Germany’s highest judicial body, ruled Scholz’s plan to shift Covid funds to plug a gap of billions of euros as illegal. The budget crisis has been a strain on Europe’s biggest economy and explains why Scholz cannot have a more hawkish approach to de-risking from China. His hands are tied.

Germany’s role in Ukraine

The rather jaded German nerves seem more coordinated when it comes to supporting Ukraine, though. Among European nations, Germany provides the largest military support to Ukraine, second only to the US. Its overtures with reviving the Weimar Triangle, a strategic alliance between Germany, France, and Poland, to coordinate efforts on Europe’s security and its companies’ long-term defence industry cooperation with Kyiv tell that Germany is playing the long game in its own theatre. It is doing this despite the difficult economic dependencies on China and Beijing’s unnerving role in the Ukraine war.

Indeed, the goals being pursued by different actors in the West appear to be conveniently veiled at the cost of each other. For Germany, perhaps it can be best encapsulated as precarious balancing between short-term survival and long-term revival.

The writer is an Associate Fellow, Europe and Eurasia Center, at the Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses. She tweets @swasrao. Views are personal.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)

Does China pose a risk to Germany. One million German jobs depend on exports to China. Chancellor Angela Merkel visited China almost once a year during her distinguished tenure. Friendship with the United States should not come at the price of conforming to its geopolitical choices. Something India is fortunately not doing in respect of our time tested friendship with Russia.