Former Chief Justice Ranjan Gogoi in one of his three letters to Prime Minister Narendra Modi earlier in 2019 had written that “One of the prime reasons why we are not able to contain the ever-growing pendency is shortage of HC judges. At present, 399 posts, or 37 per cent of sanctioned judge-strength, are vacant”.

But by overlooking police pendency, the letter considers only a part of the problem. Having the police effectively deal with the huge stockpile of cases pending investigation in India would go a long way in reducing the backlog of criminal cases.

Traditionally, the solution for expediting police investigations has been to blindly fill vacancies to meet the sanctioned police strength. However, this approach misses the point since the sanctioned number itself may be inadequate.

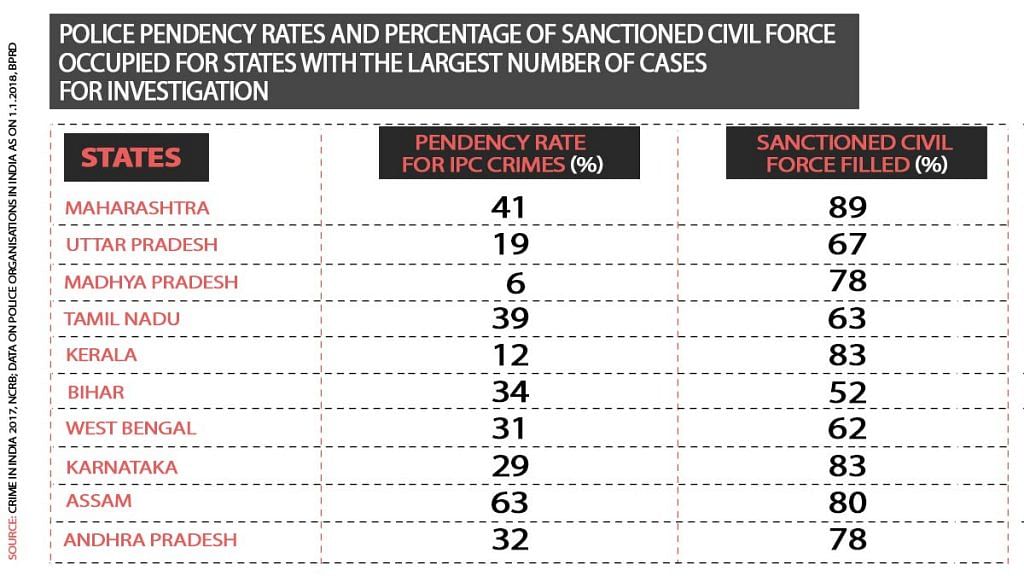

To understand these gaps in police cadres, we take a look at the relationship between case pendency rates and the extent to which states have filled their sanctioned police strength. We looked at states with the greatest number of cases piling up for investigation. These 10 states account for more than two-thirds of all pending cases in India.

Table 1 shows that Assam and Maharashtra, despite having 80 per cent or more of their police posts filled, are still reporting 63 per cent and 41 per cent case pendency. Uttar Pradesh, despite having only 67 per cent of its police force filled, reports 19 per cent pendency, whereas Tamil Nadu, with nearly the same proportion of sanctioned force filled, has double the pendency rate (39 per cent). Kerala and Madhya Pradesh, with nearly 80 per cent of police sanctioned strength filled, have managed to bring down case pendency to 12 per cent and 6 per cent.

In short, there is no correlation between these two measures; ideally, there should be a consistent inverse relationship between the proportion of sanctioned police force filled and the case pendency rate.

Also read: Dear CJI, Indians have lost faith in judiciary because we are ruled by power, not by law

Three vital considerations

The imbalance between the police strength and case pendency must be understood through these three lenses.

First, the process of estimating the sanctioned police force number is unrealistic. Every state in India arrives at its own estimate of its sanctioned police strength by taking into consideration factors like population, population density, crime incidence, communal situation, level of urbanisation, etc.

However, the system is also designed with the expectation that personnel are ‘on duty’ 24 hours a day, seven days a week – this is clearly unreasonable. This irrational demand means they are overworked and, therefore, ineffective. A 2014 study by the government-run Bureau of Police Research and Development recommended a 50 per cent increase in the current sanctioned police station strength, i.e., 3,37,500 personnel. This recommendation takes into consideration eight-hour shifts, i.e., 16 hours less than current expectations. Unsurprisingly, the study further found that 90 per cent of police station staff work for more than eight hours a day.

While states certainly need to increase their police forces, reassessing sanctioned police force numbers may be required in states like Maharashtra and Assam, which had both large police forces and high pendency rates.

Second, according to a 2012 report by the Law Commission of India, one of the main reasons for police pendency is the poor quality of investigation. This will not be solved simply by adding more personnel. Rather, their roles need to be separated and streamlined.

Police are expected to perform myriad functions such as investigation, crime prevention, maintenance of law and order, enforcement of acts, emergency and election-related duties. In Prakash Singh vs Union of India, the Supreme Court recommended the separation of law and order from investigative duties. However, it has not been implemented across India. This lack of separation impacts the effectiveness of investigation proceedings.

Making the situation worse is inadequate access to technology and lack of required infrastructure. It is worth noting that in 2017, 21 per cent of criminal cases were closed without an investigation. Close to three-fourths of those closed were due to insufficient or untraceable evidence, despite the cases being legitimate, as per NCRB data.

Third, based on our fieldwork and surveys, we found that improving investigative training is not only required but even desired by newly recruited police officers. Police personnel feel that there is not enough emphasis on the practical aspects of police work during their training. Fixing this could help the quality of investigations.

A step in the right direction is the proposed establishment of a National Police University, which was part of Parliament’s winter session agenda. The aim is to train aspiring police officers in policing, internal security, cybercrime, criminology and forensic sciences, among others. This proposal represents a much-needed push towards improving the poor quality of police training.

Also read: Not poor work conditions, not lawyers’ assault, something else hurt Delhi Police more

Addressing structural deficiencies

One caveat in all of this is that the nature of crime influences the duration and effort involved in the investigation. However, the latest report on the 2017 crime statistics, published after a two-year lag, by the National Crime Records Bureau, does not include case pendency rates organised into crime and duration categories for each state, thereby restricting a critical analysis of the situation. Also, a hesitancy to proceed with cases that involve prominent personalities and corruption influence the pendency rates, as per the Law Commission of India. Addressing these structural deficiencies would go a long way in improving the pendency situation.

Even a cursory look at ground-level realities shows that merely reducing the gap between actual police numbers and the number of personnel sanctioned by the state is not an adequate solution. It requires a re-examination of the adequacy of sanctioned police strength by accounting for more humane working hours and streamlining police functions. Data on reasons for pendency by state and by crime would help address it.

Also read: Kashmir to Assam, Tripura to Jharkhand, India’s CRPF is stretched, stressed and it’s showing

Along with better data, there needs to be a renewed focus on practical approaches to police training. This would ultimately lead to a more informed and efficient police force and effective criminal justice system.

Priya Vedavalli is an associate and Tvesha Sippy is a senior analyst at IDFC Institute. Views are personal.

In my earlier comment I forgot to mention one of the most important issues that crossed my mind right at the outset, when I began reading this report. nd that is what is the criteria adopted to decide pendency? Has the judiciary clubbed all cases registered and pending decisions on a particular day? Or had it excluded cases registered within a particular period, say within 3 months from the prescribed date?

Judiciary is the biggest threat to rule of law.

They can blame the police and the prosecution for judgments getting delayed and even going awry finally. They want people to believe that judges are pure as angels, efficient as Lord Yama, the Dharma Raja, and honest as Harichandra.

The people know better and their assessment is reflected in the phrase tariq pe tariq being bandied about our courts. Then there are the issues of corruption and nepotism.

Transparency International had once reported that the police and judiciary in India are the most corrupt. And I understand that those who reported it are being prosecuted under the contempt of court act. Such atrocities are only possible with our judiciary.

And honestly, I believe, the judiciary would be one of the factors affecting the stress levels of investigating officers. And where do they get their frustration out? On hapless citizens, of course.

Biased article. Real culprits are judges. Quality of judges is a real problem. Quantity of judges is not a problem. Form judicial ombudsman and make 1000 members of ordinary people. Give power to ombudsmen to hang judges when they do wrong things. In one year indian judicial system will be best in world after first 5 judges are hanged to death.

There is nothing wrong is pointing out that the police is under staffed and over worked. However, the truth is that even if there were more police, very little would change as far as punishment is concerned. The real culprit is the legal system and the judiciary is a key component of that. Most of the high profile cases are solved within days and yet it takes decades to convict anybody. Just recently, the terrorists who killed 80 innocent people in Jaipur were convicted after 11 years. Of course, punishment is far away because the high courts and the supreme courts are certain to take another 10 years. If you bothered to look at the details of the case, you would find that such cases keep getting adjourned and sometimes blocked for years by higher court rulings. Blaming the police is a tried and true tactic by all sides since independence; the reality remains that the legal system is the biggest culprit.

ALLOW POLICE TO TACKLE THEIR WAYS REMOVE LAW ASKING HEAD TO USE BULLET WE COPY EVERYTHING FROM ADVANCED COUNTRIES BUT WHEN IT COMES DEFENDING LOSER OPPOSITION MAKE RIOTS ONCE FOR KILL THEM