Due to Ambedkar’s struggle and contribution, the Constitution provided a new set of rights for Dalits. The provisions of representation in services and legislatures created new openings for Dalits. Reservation policies allowed Dalits upward economic mobility, and presence in educational institutions, which was earlier considered to be the monopoly and privilege of upper castes. The demand for equality, supported by political mobilisation, generated a powerful conscience among Dalits. Later, in the panchayat institutions, the reservation of seats for Dalits and women have changed certain social dynamics and have weakened the grip of the upper castes on political affairs.

It is in all these ways that the Constitution directly challenged the upper-caste privilege. Before his death, Ambedkar had proposed to write a detailed treatise with the title Revolution and Counter-Revolution in Ancient India. Ambedkar considered the establishment of democratic principles in the Buddhist era as a revolution. According to him, the counter-revolution pioneered by Brahminical forces resulted into decline and fall of those democratic principles.

This history was pointed out by him even in his last address on November 25, 1949 to the Constituent Assembly. If one was to apply that analogy to modern era, then the adoption of the Constitution of India must be seen as a form of revolution. It is to undo the effects of this modern revolution that upper castes have revolted in the form of a counter-revolution.

The Constitution has faced a consistent line of attack from the time it was being drafted. Various charges were made against the draft Constitution. Ambedkar himself stood up on several occasions to point out the shallowness in these attacks. One main charge against the draft Constitution was that it did not represent the ‘ancient polity of India’ and that it should have been ‘drafted on the ancient Hindu model of a State. . . instead of incorporating Western theories’.

Ambedkar responded that doing this would have promoted ‘a sink of localism, a den of ignorance, narrow-mindedness and communalism’, which should not happen. The draft Constitution was also criticised on the ground that it provided special safeguards for minorities. Ambedkar’s conception of minorities was much broader. It included both religious minorities as well as marginalised social groups.

According to Ambedkar, the real test for determining whether a social group is a minority or not is social discrimination. He, therefore, responded ‘Speaking for myself, I have no doubt that the Constituent Assembly has done wisely in providing such safeguards for minorities as it has done..It is for the majority to realise its duty not to discriminate against minorities’. There was also a huge debate on the constitutional provisions providing reservations for Dalits and Adivasis.

Several members wanted abolishment of reservations in any form, as they argued that it would dilute efficiency and merit. In his capacity as the Chairman of Drafting Committee, Ambedkar rejected all these claims, and stood firmly on the inclusion of reservations in services and legislatures.

As Jean Dreze has aptly noted, ‘of all the ways upper-caste privilege has been challenged in recent decades, perhaps none is more acutely represented by the upper castes than the system of reservation in education and public employment.’

Since reservation was entrenched in the text of the Constitution due to Ambedkar’s efforts, the judiciary could not strike it down directly. Instead, a larger narrative was created and promoted against Dalits and Adivasis, where they were declared to be incompetent and inefficient to be a part of services and educational institutions. For a long time, the Supreme Court of India held that reservations dilute efficiency to some

extent. There was no empirical backing in support of this claim, yet the society at large and the Supreme Court kept on repeating this myth to create caste prejudices against Dalits. Economists Ashwini Deshpande and Thomas E. Weisskopf have demonstrated through their study that reservations do not dilute efficiency, rather these might enhance efficiency. Another way of weakening the reservation system is the narrative on the creamy layer, which has been promoted in recent decades. According to this narrative, only the ‘cream’ within Dalits, which comprises a distinct group taking away the entire benefit of reservation, and thus should be excluded from benefits.

Thorat, Tagade, and Naik, in their study on myths on reservation, show that the beneficiaries of reservation policies have mostly been economically backwards. Furthermore, the upward economic mobility of the lower caste as a result of reservation and other supportive policies has met with the rise in atrocities and abuses against Dalits.

While one may argue that all atrocities are not committed against beneficiaries of reservation in cities, there is empirical evidence that the rise in atrocities has happened with the upward social mobility of Dalits. In that way, the progress achieved by Dalits as a result of constitutionalism has been responded to by upper castes by way of mythical propaganda and atrocities. Every method has been adopted to discredit the reservation policies.

Furthermore, there were once efforts by right-wing Bhartiya Janata Party-led government to review the Constitution in 2000 to do away the ‘inability of the Hindutva forces to realise their politically motivated agenda of creating a Hindu nation within the existing constitutional framework’. Then-Indian President, K. R. Narayanan, who came from the Dalit community, publicly opposed any such proposal. The proposal was thereafter changed to review the working of the Constitution, instead of the Constitution itself.

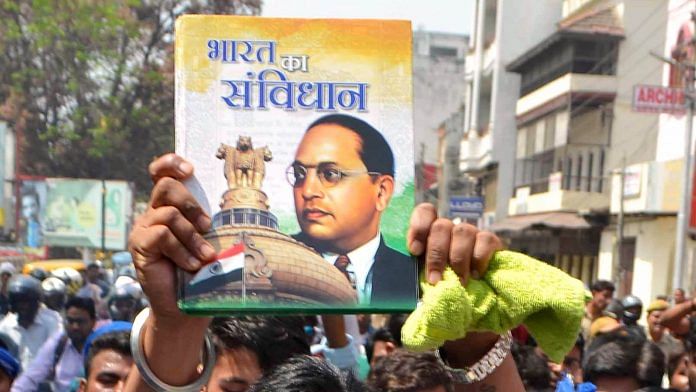

The Indian legal academia also maintains a form of untouchability on the issues of caste discrimination and the rights of Dalits even within the academic spaces. Most of the scholarly works on the Indian Constitution shy away from discussing Ambedkar as a central figure in constitutionalism, despite his influence during several decades of constitutional reforms (1919–1950). It is only recently that Ambedkar has now resurged in the public sphere (Perrigo, 2020), but credit must be given to the anti-caste movement, which kept the memories of Ambedkar and his contribution to the Constitution alive.

This excerpt from a paper titled ‘Ambedkar’s Constitution: A Radical Phenomenon in Anti-Cast Discourse’ has been published with permission from Brandeis University. Read the whole paper here.