Quite like the much-touted ‘idea of India’, the ‘idea of Pakistan’ has been crystallising and gaining currency lately. “Jinnah’s Pakistan” — a catchphrase coined by a Pakistani Parsi journalist, Ardeshir Cowasjee, has become a new totem of the Pakistani liberal class, and their counterparts on this side of the Radcliffe Line.

It is claimed that all that Mohammad Ali Jinnah wanted was to secure the secular interests of the Muslim minority in India. To that end, he led a movement to carve out a separate country, which he intended to be a forward-looking modern and secular polity, and not a backwards-looking theocracy. That the Partition jeopardised the interests of the Muslim minority in what would remain India while securing that of the Muslim majority in what would become Pakistan is a mere aside to the subject of this article.

In a recent article published in ThePrint, Yasser Latif Hamdani, author of a new biography of Jinnah, severely castigated the ousted prime minister Imran Khan for reneging on Jinnah’s ideals and damaging the idea of Pakistan by invoking the Islamic utopia of the State of Medina under Prophet Muhammad and his pious Caliphs. He disparaged historian Venkat Dhulipala for his 2015 book on the genesis of Pakistan, Creating a New Medina. Hamdani says, “The truth is, at no point did the All-India Muslim League or its president Mahomed Ali Jinnah invoke Medina or speak of a theocratic State of any kind. The entire idea of Pakistan had to do with a Hindu-Muslim counterpoise on secular issues such as representation, jobs, and so forth. Religion was just not the point.”

A counterpoint to this view is Ishtiaq Ahmed’s recent tome, Jinnah: His Successes, Failures and Role in History, in which he asserts, “the fact was that Pakistan was by default an ideological state grounded on a confessional basis: religion was the basis of nation and that too a religion whose most coveted and revered political characteristic was the state of Medina.”

Also Read: Indian Muslims are silent over Tabrez Ansari because of Muhammad Ali Jinnah

Jinnah and Pakistani State

If some people harboured any doubt regarding the nature of the Pakistani State, Jinnah laid that to rest in his 25 January 1948 address to the Karachi Bar Association by declaring that 1,300 years ago the issue was solved and the Pakistan Constitution would be framed in the light of Islamic Sharia. His letter to Hassan al-Banna, the leader of the Muslim Brotherhood movement of Egypt, which wanted a state on the lines of the Medinan utopia, and setting up of the Department of Islamic Reconstruction under Muhammad Asad, formerly Leopold Weiss, an Austro-Hungarian Jewish convert to Islam, were steps establishing a sharia-governed Islamic state.

This is the later end of the continuum, which was inaugurated with Jinnah’s speech at the Lahore session of the Muslim League on 22 March 1940, a day before the Pakistan Resolution was adopted. Jinnah expounded the religious reasoning underlying the two-nation theory: “The Hindus and Muslims belong to two different religious philosophies, social customs, and literatures. They neither intermarry nor interdine together, and, indeed, they belong to two different civilisations which are based mainly on conflicting ideas and conceptions.” A year later, at Aligarh Muslim University, he projected the idea of Pakistan as the desperate solution for Islam-in-danger: “The only goal if you want to save Islam from complete annihilation in the country”.

The desperation to save Islam from the imagined annihilation was so acute that Jinnah was prepared to sacrifice the remaining Muslims of India in order to liberate those of the Muslim-majority provinces. In a speech at Kanpur on 30 March 1941, he blurted out a shockingly brazen statement: “In order to liberate 7 crore Muslims where they are in majority, I am willing to perform the last ceremony of martyrdom if necessary and let the 2 crores of Muslims be smashed”.

It was with such desperation to save Islam from annihilation that Pakistan was cut out of India. There was no way it could be anything other than an Islamic state, which it has been since conception and inception. The Objectives Resolution in the Constituent Assembly, which committed Pakistan to the Islamic rule was a natural corollary of the idea of Pakistan and the ideological forces behind it, and not a deviation from Jinnah’s professed aims, or how Pakistan was popularly imagined, understood and fought for. It wasn’t done under any duress from ulema like Maulana Maududi or Shabbir Ahmad Usmani but was a genetic inevitability.

Also Read: Jinnah didn’t join the Muslim League right away. He had one condition

Secularism and Pakistan’s liberals

Jinnah’s speech of 11 August 1947 went on to become the proverbial philosophers’ stone for the liberal class that had no recourse except this to weave a credible narrative. This was a one-off speech in which he said, “You are free; you are free to go to your temples; you are free to go to your mosques or to any other place or worship in this State of Pakistan. You may belong to any religion or caste or creed that has nothing to do with the business of the State”. And, that “in course of time Hindus would cease to be Hindus and Muslims would cease to be Muslims, not in the religious sense, because that is the personal faith of each individual, but in the political sense as citizens of the State”. This speech was an exception ever since the Pakistan Resolution of 23 March 1940 to 11 September 1948 when he breathed his last, with nothing of the sort to have either preceded or followed it. It wasn’t a commitment to secularism, a word Jinnah never used.

According to Ishtiaq Ahmed, rather than being a blueprint for the future Pakistan, it was aimed at convincing the Indian government that since he was going to treat his minorities well, India too should do the same, and not push its 3.5 crore Muslims into Pakistan, which would make the nascent country crumble before it got onto its feet. Ironically, Jinnah wanted to save Pakistan from the migration of those very people in whose name it was carved out — Indian Muslims from the Muslim minority provinces.

It has become a liberal fad to absolve Jinnah of the guilt of Partition, and to project him as a secular man who, having won Pakistan in the name of Islam, wanted it to be a modern and liberal-secular country. The liberal class on both sides of the border should know that true liberalism consists of a robust critique of the politics that Jinnah practised; that his legacy is not the one to be invoked, and is best forgotten.

Also Read: Imran has damaged the idea of Pakistan. Don’t expect it to turn into a normal country soon

Islamic modernism has changed little

Thrusting secularism on Jinnah because of his Western deportment is, to say the least, silly. He might not have been a practising Muslim, and he might have imbibed alcohol and partaken of pork, but being irreligious is not quite the same as being secular. There is no correlation between one’s religiosity or the lack of it, and his commitment to secularism. Gandhi was deeply religious and secular; Jinnah was irreligious and communal.

Why the liberal class in Pakistan and their counterparts in India keep resorting to Jinnah, and projecting secularism on him, is because of the convoluted or rather perverse or fake modernity among the subcontinental Muslims as shaped by the Aligarh Movement, which saw modernity not as a value but as an instrument to be back in the game — the old game of ruling the country in the name of Islam.

They developed a critique of the ulema class and the orthodox Islam for not keeping pace with the changing times, which led to the loss of power. Modernity and its accoutrements were sought not for the evolution to the higher stage of progress, but for restoring the bygone era of supremacy. Thus it was in 1947 and thus it remains in 2022.

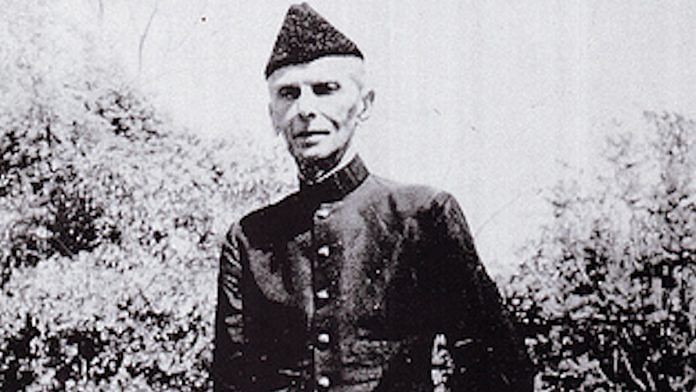

Islamic Modernism in India didn’t bring any change in the Muslim ruling class’ attitude towards Hindus, Hinduism and Hindustan. Therefore, Pakistan, being the Muslim State in India, whether modern or Islamic, remains in the ‘Ghazwa-e-Hind’ mode. From the Lahore Resolution to the Objectives Resolution to Bhutto’s Islamisation to Zia ul-Haq’s ‘Nizam-e-Mustafa’ to Imran Khan’s ‘Riyasat-e-Medina’ — there has been an unbroken linear progression. The Jinnah of Savile Row suits and the one of Sherwani and Karakul cap is one and the same person.

Ibn Khaldun Bharati is a student of Islam and looks at Islamic history from an Indian perspective. He tweets at @IbnKhaldunIndic.

(Edited by Srinjoy Dey)