There are promises galore in the run-up to the assembly elections in Goa, Punjab, Uttar Pradesh, Manipur and Uttarakhand in February/March 2022. Despite all talks of reforms in agriculture and rationalisation of subsidies, political parties seem to have run out of ideas.

In Uttar Pradesh, the Bhartiya Janata Party (BJP) has promised free electricity for farmers in the next five years. The Samajwadi Party (SP) has promised free electricity for irrigation and ‘debt free’ farmers by 2025, perceptibly indicating a loan waiver. The Congress has promised yet another round of loan waiver for farmers. In Punjab, the NDA has promised a farm loan waiver of up to Rs 5 lakh. The Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) has promised free electricity for agriculture in Uttarakhand.

Farm loan waivers are a favourite announcement during election time. The parties promise to absolve an indebted farmer from repaying their outstanding debt. Farmers do not benefit from it directly, but not having to pay back loans increases liquidity in their hands and when old outstanding debt is settled, farmers can access fresh loans from institutions.

Over time, these waivers have gained political legitimacy, albeit ostensibly. According to our research, between 1987 and 2019, political parties lost elections only four out of 21 times following a promise/implementation of farm loan waiver. With more than 80 per cent success rate, these waivers offer a rather robust formula of electoral success.

But if waivers were such havens of solution to all farmer problems, then why are they considered necessary every few years?

In an upcoming research report on farm loan waivers in India (March 2022), we explore various aspects related to fiscal, economic, social and behavioural impact of farm loans waiver schemes on farmers, state budgets, banking sector and particularly on credit culture in India.

Some key learnings from our analysis of state budgets are presented in this article.

Also read: Farm loan waivers are announced in election season. Karnataka worst offender

Where do states get the money

Farm loan waivers are expensive programmes. Punjab’s 2017-18 loan waiver was expected to cost the exchequer Rs 10,000 crore, which was 9 per cent of the state’s GDP that year. In the same year, Maharashtra and Uttar Pradesh too implemented their loan waiver schemes. They were to cost Rs 34,020 crore and Rs 36,000 crore respectively, which were about 12-13 per cent of the states’ GDP in that year. How do states accommodate or fund such large expenditures?

Usually, governments either increase their borrowings or impose some form of taxation and/or shuffle funds between different governmental departments to fund such waivers.

We studied three farm loan waiver schemes implemented by Punjab (Karz Maafi Yojna), Maharashtra (Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Shetkari Sanman Yojana) and Uttar Pradesh (Kisan Rin Mochan Yojana) in the year 2017-18. Using the detailed data from state budget documents, among other things, we found the following things.

As the cost of waiver is large, states disburse waiver amounts to banks in a phased-manner spread across a few years. For instance, for the 2017-18 scheme, Maharashtra and Uttar Pradesh released 74 per cent and 83 per cent respectively of waiver amounts in the same year, however, in Punjab, 64 per cent of waiver amounts were released in the following year in FY 2018-19. By deferring the payments, state governments manoeuvre fiscal space.

Also read: Indian farmers need a new distress index. Just suicide data won’t do

Do waivers eat into more important expenditures

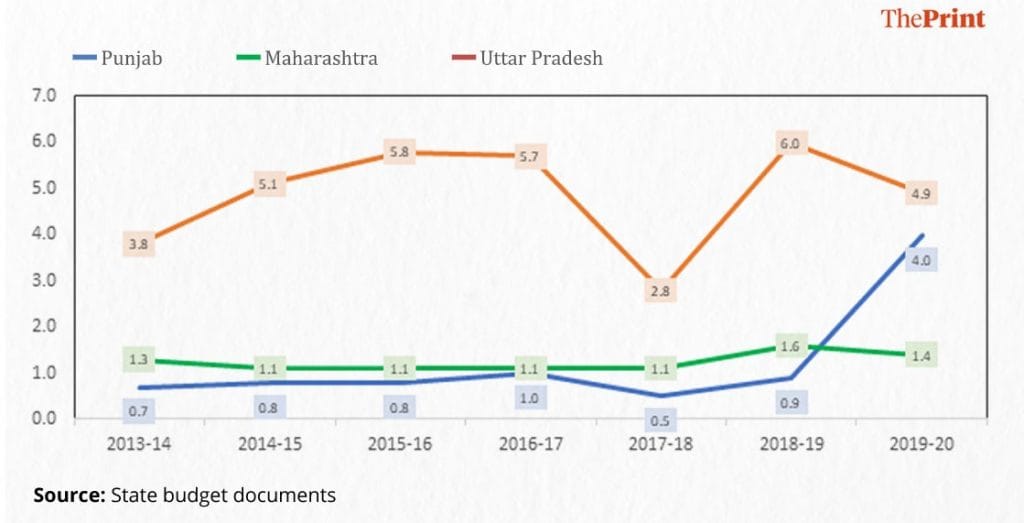

Capital outlays (capex) are expenditures made for asset creation or reduction of liabilities. Capex is associated with future income generation capacity of a state. Both in Punjab and UP, capital outlays were lower in the year in which maximum waiver amounts were released to banks. In Punjab, capital outlay as a percentage of state GDP (CO/GSDP) halved from 1 per cent to 0.5 per cent in 2017-18 (though it recovered in 2018-19, it was still below 2016-17 levels). In Uttar Pradesh, the dip was even sharper, where the capex ratio decreased from 5.7 per cent in 2016-17 to 2.8 per cent in 2017-18 (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Capital Outlay as percent of GSDP (per cent)

However, in the case of Maharashtra, this dip is not visible.

Major inter-department reallocation observed

Our study found that compared to normal years, budget allocations of different departments saw a major reshuffle in the year when most waivers were disbursed.

Of course, with farm loan waivers, allocations of implementing departments increased manifold. In Punjab, allocations of ‘agriculture’ department increased by 66 per cent; in UP, that of ‘agriculture and allied activities’ department increased by 610 per cent and in Maharashtra, that of ‘cooperation marketing and textiles’ department grew by 887 per cent.

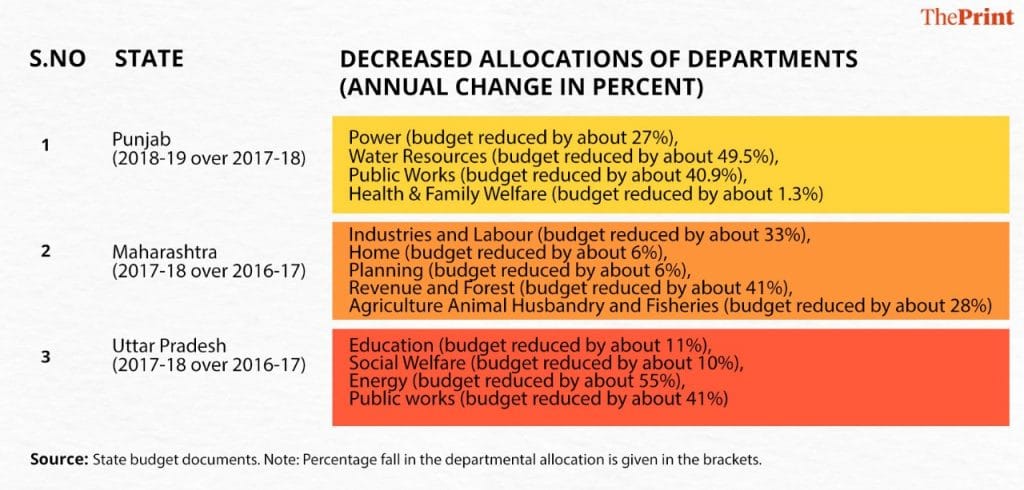

At the same time, allocations of many other major departments fell. The most notable fall was observed in allocations of the following departments: power, water resources, public works, health and family welfare, education, social welfare, energy, irrigation, industries and labour, among others (for details see Table 1).

Table 1 Change in Inter-department allocations

Even though fall in departmental budgets may not be exclusively attributable to loan waivers, it does highlight a case where budgetary adjustments are made in a discernibly ad-hoc manner to accommodate expensive schemes like waivers.

By reducing expenditures on key departments like education, power, energy and water resources, among others, state governments are crowding-out investments that are vital for a state’s future.

Besides, farm loan waivers also do little to alleviate the farmers’ distress.

Also read: Direct payments to farmers will work if govts can be agile, flexible like arhatiyas

Farmers’ vicious cycle

Due to multiple factors, farming in India is risky. The production cycle, coupled with other factors, makes it impossible for farmers not to be indebted, and recurrent losses and falling margins make them default on their loans. Default deepens their distress, sometimes driving them to take the extreme step of suicide. A loan waiver addresses this indebtedness, which appears more to be a result or a symptom of a much more complex problem. Therefore, with unaddressed factors of distress—like successive crop failure(s), inability to get remunerative prices for their crops or a personal loss—the condition of farmer who benefitted once under a loan waiver scheme only improves for a short time, and in a matter of just a few years, they are indebted again and driven to a point of needing another round of waiver.

So, through a farm loan waiver, a state government is not only trading a state’s future capacities for the present, but is also not able to adequately address the present. Not to mention other side effects of waivers on the country’s credit culture and banking sector’s incentive to lend further. Overall, political parties need to innovate to find solutions that make political and economic sense and truly empowers farmers in the longer run.

Saini and Hussain are Senior (Visiting) Fellows at ICRIER and Khatri is Consultant, Arcus Policy Research