Skilled immigrants pay for elderly Americans’ retirement & health care, maintenance of roads, sewers, electrical grids, police & firefighters.

Skilled immigration is good. The U.S. economy depends on it. But the nation’s system for admitting educated workers needs major improvements.

That is the central message of “The Gift of Global Talent: How Migration Shapes Business, Economy & Society,” a new book by Harvard Business School professor William Kerr. In this terse but readable volume, Kerr — who has spent much of his career researching skilled immigration and the technology industry — methodically explains all the benefits that the U.S. reaps by bringing in smart, talented foreigners, and counters almost all the objections. As the U.S. immigration debate heats up, and President Donald Trump takes actions to deter skilled workers from coming, Kerr’s book should be a must-read for every policy maker.

The basic reason skilled immigrants are good for the economy is because they produce a lot of economic output — they write the software, design the products, and start the businesses that make the U.S. technology industry the best in the world. As of 2016, Kerr calculates, 29 percent of college-educated STEM workers was foreign-born, and about a quarter of all patents were filed by an immigrant.

Even more importantly, skilled immigrants complement both skilled native-born workers and each other, by exchanging ideas. They also create a deeper market for companies seeking employees and venture capitalists looking for entrepreneurs to fund, helping keep both employers and financial backers in the U.S. These effects all depend on skilled workers being physically close to one another. Without a constant influx of the best and the brightest, Silicon Valley and other American world-beating technology clusters could easily lose their lead to rival cities in other countries.

This clustering effect is probably why skilled immigration doesn’t hurt native-born American workers. Some researchers find that when a company hires more skilled workers, it hires fewer natives. Others, including Kerr, find the opposite. At the level of a city, however, the positive effect seems unambiguous — more workers with H-1B visas means higher wages and more jobs for college-educated native-born workers. This suggests that the positive effect of the local networks skilled immigrants create outweigh any competitive pressure they create, meaning everyone benefits.

Everyone in the U.S., that is. But what about the countries that send their talented people abroad? Don’t they suffer from brain drain? Kerr cites evidence that the U.S.’s gain doesn’t necessarily translate to other countries’ loss. Skilled immigrants send technology and investment back to their home countries, helping to build cross-border networks of innovation. What’s more, the possibility of getting a job in the U.S. motivates lots of people in foreign countries to get more education, which often actually increases the stock of local talent. For a small country, brain drain could be a drawback, but for giant countries like China or India — which happen to be the two biggest sources of skilled immigration to the U.S. — it’s not a problem.

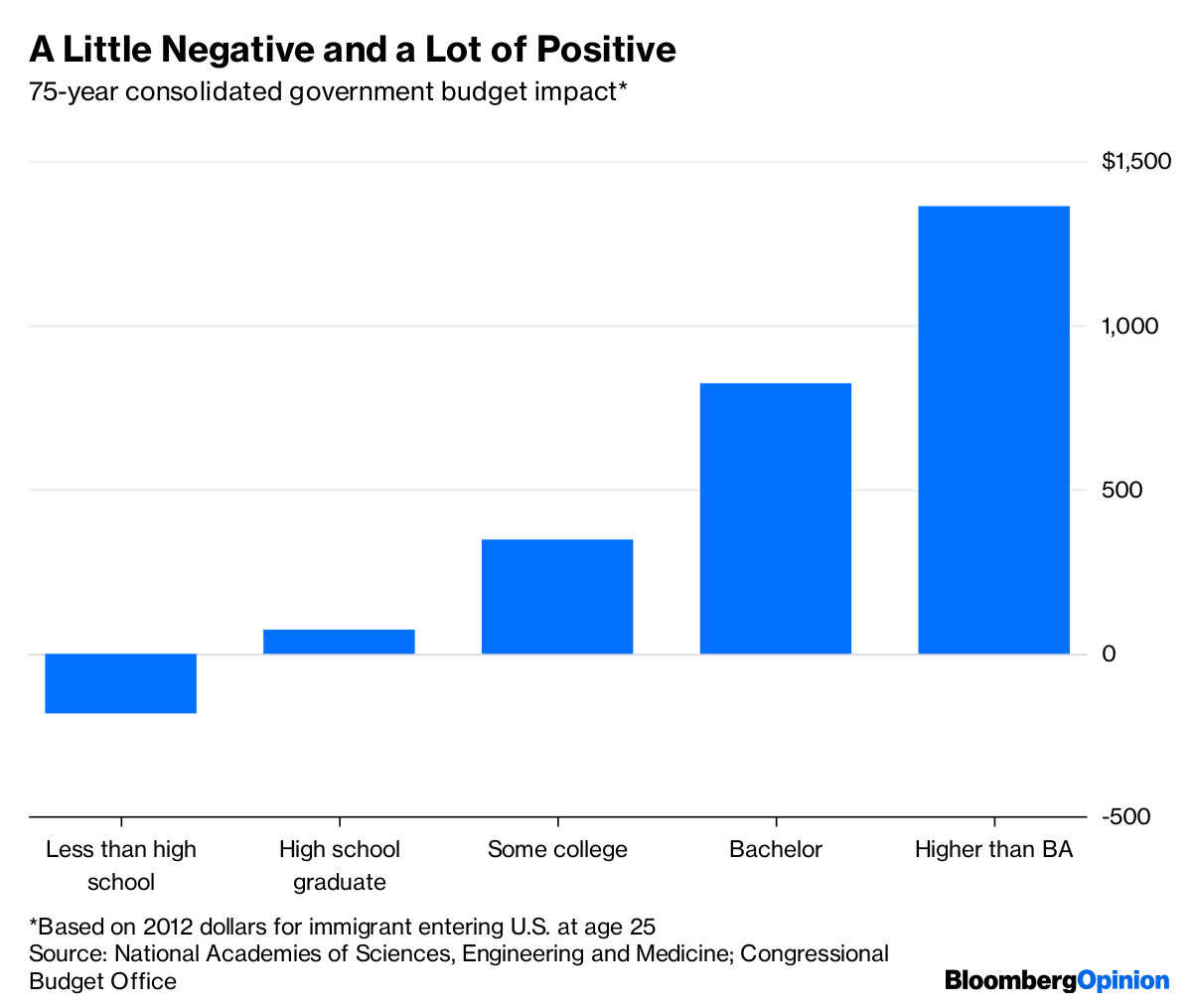

Beyond the wage and employment boost they create for native-born Americans, skilled immigrants contribute plenty to government coffers:

Skilled immigrants aren’t just invigorating the economies of the U.S. technology industry and cities like San Francisco — they’re paying for elderly Americans’ retirement and health care, for maintenance of roads and sewers and electrical grids, for police and firefighters.

Given all of these benefits, you’d think the U.S. would be stumbling over itself to open the door to more skilled foreigners. But even before Trump started trying to close the gates, the U.S. system was badly in need of upgrading.

For one thing, too many H-1B visas go to low-paid workers in companies focused on cheap, low-value contract work. These workers aren’t the highly productive type, and they’re crowding more qualified foreign employees out of line. Kerr suggests allocating H-1Bs not by lottery as they are now, but by salary — the more that a company is willing to pay for a foreign worker, the quicker they can get a visa. That change would also ease Americans’ fears about wage competition.

A second change would be to allow H-1B workers to apply for permanent residency green cards on their own, without having to be sponsored by their employers. Now, during the green-card application process, H-1B holders are essentially required to stay at the company sponsoring them. Breaking that tether would give them the chance to move around the country, spread ideas and technology, and seek higher wages, which in turn would relieve pressure on native-born workers who feel like they have to compete with indentured colleagues.

These are Kerr’s preferred solutions to the inefficiencies of the H-1B system. But there are also a number of other important measures that could allow the U.S. to make better use of global talent. Letting states and cities sponsor immigrants would direct highly productive, tax-paying newcomers to struggling regions, such as the Rust Belt. A Canada-style points system for green cards would create a parallel pathway for skilled immigrants. And removing country caps for employer-based green cards would allow the U.S. to get more of its skilled workers from China and India, meaning small countries wouldn’t lose their most talented workers.

In an age in which most sources of rapid growth are drying up, skilled immigration is one of the last free lunches that the U.S. has. Even after Trump’s election, many talented foreigners want to live and work in America. The U.S. needs a better system for letting them come and contribute to the country’s greatness.-Bloomberg