There is a fatalism in current Indian politics that the Narendra Modi-led government will return to power in 2024. This has much to do with Modi’s own persona and popularity ratings that remain high after nearly a decade of rule. The focus on personality, however, hides in plain sight the crisis of party politics in Indian democracy. If Hindutva is the ascendant idea of India today, then ideological and political contest remains multipolar and even fragmented.

The central paradox of Indian politics today is that while there may be two ideas and ideologies on the identity of India, they are not represented by any two national parties despite an astonishing number of political parties in the country.

If anything, a successful coalition of opposition parties, as is being floated currently, will extract the greatest amount from and will be at the cost of the Indian National Congress. As the only party with a national footprint, any prospect of a grand alliance will be staked on and paid for by the Congress. This crucial lack of bipartisanship, arguably, has only led to the domination of the Bharatiya Janata Party or BJP’s Hindutva politics.

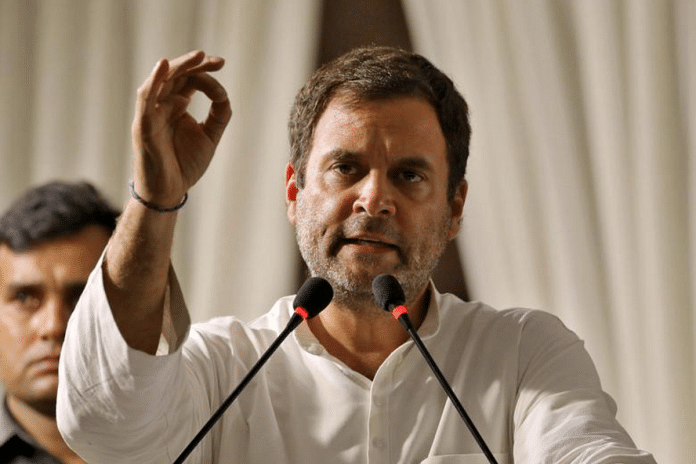

For all the recent talk, photo ops, and frenetic activity among India’s opposition politics, the idea of unity is not only spectral but mainly lacks confidence and even credibility. Here, Modi can take further credit for uniting, if momentarily, what is ultimately divergent. There is, after all, little that binds an Arvind Kejriwal with a Rahul Gandhi, apart from the sharp wedge of court cases prosecuted by an overzealous State machinery.

Ever since the arrival of multi-party politics in the late 1980s, India has continued with the model of one dominant party in a sea of several contending parties. There are two reasons why Indian politics isn’t bipartisan. One is ideological, and the other is caste or the political remaking of India’s social fabric.

Also read: Rahul Gandhi’s ‘Jitni abaadi utna haq’ call isn’t about elections or Mandal. Goal is…

AAP and Congress don’t go together

The new opposition unity talk is based on a thin ideology, which is primarily posited as anti-BJP or Hindutva. Without a powerful, positive precept and animating idea, the opposition is but just that — a single-minded non-force. The history of coalition governments in India, starting with the first-ever such experiment in 1977 (with the formation of the Janata Party) and beyond, especially through the heyday of coalitions in the 1990s, reveals the coalition pattern to be strongly non-ideological.

Earlier, the only binding force was a strong anti-Congress sentiment, which indeed ceded the ideological space to a rising BJP for it to capture the national mood through the LK Advani-led Ram Mandir movement. The opposition has yet to recover from that loss of ideological momentum. The singular failure of the 10-year Congress-led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) rule was its inability to forge a political and emotional dynamic around developmental nationalism that had led to its ascendence to power in the first place.

In the same decade, the BJP transformed itself with aggressive agility as it sought to absorb the full range of nationalist sentiment. Whether it is development or foreign policy — to say nothing of its pursuit of a Hindu First polity — the BJP’s ideological space is now both broad and exclusionary.

By contrast, the new momentum associated with the Aam Admi Party is resolutely anti-ideological. As a key opposition player, the party’s rise and potential pose the greatest threat not to the BJP but to the Congress, and this threat will not be restricted to direct competition in places like Delhi and Punjab. Overarchingly, the AAP and the Congress are vying for the same ideological and political space of the centre.

While the Congress has redoubled on capturing ideological spirit as witnessed through the Bharat Jodo Yatra, an alliance with the AAP poses an existential threat. Unlike the Trinamool Congress, the most successful regional off-shoot of the Congress, the AAP is not restricted to a strict linguistic or regional identity. The potential of the AAP is directly tethered to its ability to absorb and overtake pockets of the Congress itself. As such, the co-presence of the AAP and the Congress within a broad coalition makes opposition unity not only incoherent but unviable. Any viability will, above all, dilute any new and counter-ideological momentum that Indian polity desperately needs.

Any ambitions for a national footprint for the Congress party will now require the slow work of ideological remaking rather than the easy joining of hands with others for piecemeal gains. An alliance, especially with the AAP, could not only haemorrhage it further but could also be fatal for India’s oldest party. If anything, the BJP’s rise is instructive, for it shows how the party held its own ideological nerve at its weakest point in the 1980s and started from ground zero, giving up immediate gains and succeeding by playing a medium-term game for national domination.

Also read: BJP politics in Karnataka is letting Modi down. It’s becoming another Congress

Mandal 2.0

Except for the AAP, Indian opposition parties remain resolutely regional and tethered to one or two dominant sub-groups of other backward classes. Experts are now saying again that any hope of opposition unity in India must rely on the revival of caste or Mandal-style politics. This is not mere fantasy but drawn from the fact that the BJP has not been successful or even competitive in close to a third of parliamentary constituencies. The fact that nearly half of the state assemblies do not belong to the BJP further points to the fragmentary landscape that disallows the party a complete hegemony of Indian politics.

Because the Other Backward Classes (OBC) have emerged as the pivot of multi-party politics in India, conducting a caste census has become a crucial and visceral political demand for the next Lok Sabha election. Yet, as the electoral fortunes of the Samajwadi Party — the centrepiece of Mandal-inspired OBC politics — highlight, these parties, too, have peaked in their social bases. While OBC parties have proliferated, they have been unable to form broader social coalitions, especially with the Dalits.

Nevertheless, any appeal to Mandal politics while speaking to social justice countervails against a coherent national opposition to the BJP. This is even more challenging now as the BJP has been assiduously targeting the OBC as a critical new voter for its agendas. In short, the BJP is following an aggressive agenda of social incorporation like it executed its ideological expansion, focusing on increasing its voter share both with the OBCs and Dalits. This agenda of social incorporation limits the potential of OBC-based regional parties. As such, a rainbow coalition of OBC parties, without the Congress, also makes the opposition platform a non-starter.

The critical distinction between the Congress in its heyday and the BJP today is that the latter has created its own space through a politics of aggressive incorporation. If the Congress fragmented along regional and caste lines to create new parties, the BJP followed the opposite trajectory of bringing caste-based fragments and sub-groups into its fold. In short, the clash between the BJP and the opposition is one between aggressive incorporation and a friable coalition of fragmentary interests. This might, and as it does, work for the opposition in state assembly polls, but it offers little to no room for expansion for a new and alternative national consensus.

Whether approached on ideology or through the prism of caste/regional politics, any national opposition coalition and challenge to the BJP will weaken the Congress. If anything, the lesson of the anti-ideological and cynical coalitions of the 1990s is that they empowered the BJP for it to rise as a dominant ideological force. Without effective bipartisanship, Indian democracy will continue to suffer under cynical coalitions and a crucial deficit of representation.

Opposition unity, spectral or cynical, ironically poses the greatest question on the future of the Indian National Congress. Whether or not the Congress will hold its own nerve and rebuild will determine whether India will become truly bipartisan.

Shruti Kapila is Professor of history and politics at the University of Cambridge. She tweets @shrutikapila. Views are personal.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)