Unlike last year’s Raisina Dialogue, which saw Russia’s foreign minister, Sergey Lavrov, take the centre stage, this year saw an unprecedentedly large presence of foreign ministers and diplomats from the European Union. With the EU’s growing charm offensive across developing countries ever since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, largely intended for India, their overarching message at the conference held from 21-23 February in New Delhi was unambiguous: India should reconsider its longstanding ties with Russia and support Ukraine’s righteous war of defence in accordance with international laws.

In spite of the ongoing Israeli carnage across Gaza and the West Bank, in which several EU countries remain adamantly indifferent and supportive of Israel’s actions regardless of international laws, some of these ministers still insisted on pushing an incomplete account: merely Indian (as opposed to continuing EU and third-party country) purchases of Russian fuels are sustaining Russia’s wartime economy and arms capabilities. Earlier, at the Munich Security Conference in Germany (16-18 February), India’s foreign minister, S Jaishankar, faced similar claims and advice. As part of defending India’s approach to multipolarity, whose one premise among many is to maintain “a strong Russia”, Jaishankar curiously also emphasised: “Different countries and different relationships have different histories. I don’t want you to inadvertently give the impression that we are purely unsentimentally transactional, we are not.”

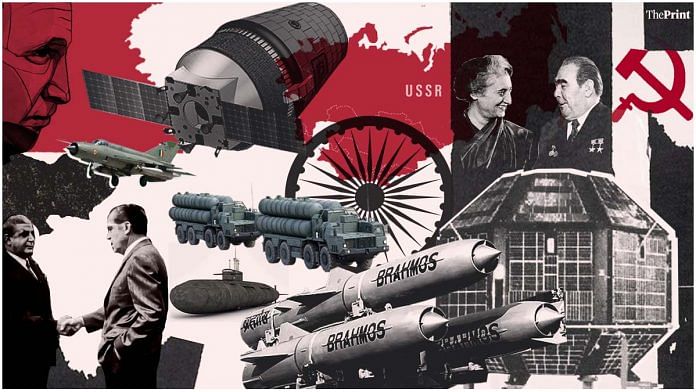

Beyond the historically grounded ideological-political and geopolitical reasons behind the solidity of contemporary India-Russia ties, it’s worth contemplating the meaning behind “transactional unsentimentality” as an overlooked framing. Notwithstanding their likely limited influence on the overall policy positioning towards Russia, the assertion made for such framing may testify to how the role of “affectionate politics” remains underestimated in Western calculations of Russia’s lingering global clout.

Affectionate politics can be seen as comprising: first, feelings and emotions cultivated from multi-faceted and longstanding exposure to any aspects of historical and contemporary Russia, including the former Soviet Union (USSR), its culture, friendships, mentorships, and schooling and training held by individuals and broad collectives of people, including those in decision-making bodies; second, individual and collectively held gratitude for past deeds during one’s own existential crises; and third, the lingering legacies of past ideological idealisms and romanticism associated with what the bygone USSR tentatively espoused to push forward for newly independent nations in the former ‘third world’, including India: a new, decolonised and equal world order.

Also read: Russia’s gains in Ukraine more symbolic than strategic. But Kyiv is in a worse situation

Affection for Russia—India to Vietnam

There is a tendency to analyse and cast judgements on any country’s approach to Russia (or for that matter, any great power or giant neighbour) by its policy positioning and manoeuvres, in other words active policy outcomes. But going further in detail, these processes are ultimately made up of individuals, from the top to bottom of decision-making bodies, whose worldviews are partly shaped by their own personally held affections to Russia. If such individuals consist of the majority of those with power and influence in government as much as among citizens in the broader society, then such affections may underpin the actual characteristics of a collective consensus and thereby a national approach towards Russia.

This is one suggestive way to understand how Jaishankar’s description of India’s approach to Russia as not being transactionally unsentimental comes into play. This description resonates deeply with Vietnam, another country in Asia with a long diplomatic and overall affectious history with Russia. Nowadays, India and Vietnam are perhaps the only Asian states that enjoy overall strong ties with both the United States and Russia, in part to withstand ever-more intensifying great power frictions across the United States, China, and Russia. In 2021, Kurt Campbell, then serving as the US National Security Council coordinator for the Indo-Pacific, declared that the future of Asia in the 21st century would be decided by India and Vietnam.

It is, therefore, imperative to explain the enabling historical contexts behind their enduring sentimentalities towards Russia beyond the logics of geopolitics and realism. While both India and Vietnam have officially remained neutral over Ukraine, pro-Russia perspectives have received extensive media coverage, often implicitly sympathetic. These perspectives have not only been unveiled and promoted through regular interviews with Russian ambassadors, diplomats, and officials, while their Ukrainian counterparts continue to receive a cold shoulder, but also through interviews with their own ordinary citizens. In the spirit of their nominal neutrality towards the war, media coverage featuring such citizens has often revolved around them rekindling incredibly personal, soft, and appreciative memories, including about their Russian teachers, supervisors, friends, studies and training, and exposure to artwork, literature, and poetry.

But many individuals have also gone beyond rekindling their past intimate experiences to critically reflect on them in the context of the realities of a war between two nations that both generously aided India and Vietnam during various moments of the Cold War. For such individuals, the acts of rekindling and memorialising also served to legitimise their ultimate opposition to the invasion of Ukraine, as well as bring to light the discontents of the Soviet and post-Soviet society and economy behind today’s calamities. This explains why the initial phases of the outbreak of the war triggered intense and conflicted feelings for many people across the developing world who were once and remain deeply influenced by their formative experiences with the modern Soviet and post-Soviet world, especially in Russia and Ukraine.

Ahead of the UN General Assembly voting in March and April 2022, which involved condemning the Russian invasion, demanding the withdrawal of Russian troops from Ukraine’s territories, and expelling Russia from the UN Human Rights Council, retired Vietnamese diplomats privately admitted that gratitude towards Moscow’s past support during one’s own crises and wars mattered in the calculations behind their votes. This has also been implicitly admitted, for instance, by Russia’s envoy to Cambodia, whose official support for Ukraine from the beginning has ever since been met by Moscow’s repeated reminders about its historical role and contributions in deposing the genocidal Khmer Rouge regime (1975-79) and rebuilding post-war Cambodia (1979-91). Sentimentally, it felt betrayed irrespective of its illegitimate justifications, as well as Cambodia’s own history concerning foreign occupation behind its support.

When various EU envoys to Vietnam sent a letter in March 2022 calling for Vietnam’s support for Ukraine, one argument made was as follows: “We understand the importance of the historical relationship between Vietnam and the USSR. The USSR came to your aid when needed when other countries did not. But the USSR has ceased to exist, and we are now in a new era.”

However, when one engages with the lingering role of affectionate politics towards Russia within India and Vietnam, it’s not difficult to see why this argument may come across as dispassionate. Alongside the fact that India and Vietnam continue to have a sizable segment of past and current leaders, civil servants, and ordinary citizens with deep past exposures to the USSR, at the political level, they still fondly appreciate Moscow’s past support for their national political, military, and economic well-being when their ties with the West were at their worst states during the Cold War, especially during the bloody 1971 War of Independence for Bangladesh and the 1978-89 war against the Khmer Rouge regime in Cambodia. In both historical instances, whose memories remain fresh and alive, Jaishankar argues, “strategic calculations of the West trumped public outrage.” Ahead of these two wars, India and Vietnam had to abandon their non-alignment and balancing acts in favour of signing formal alliances with the USSR.

Also read: Stay neutral in Russia’s war. India’s caution follows principle of international relations

The past support isn’t forgotten

The supposed rejection of transactional unsentimentality towards Russia is also historically rooted as an implicit rebuke of China during the Cold War as much as in the present. During the most challenging moments of the China-Soviet split and the world-shaking US-China rapprochement, both India and Vietnam were on the receiving end. By insisting that India’s approach to Russia is not entirely transactionally unsentimental, in the context of his recent book, The Indian Way (2020), Jaishankar’s overarching theme is in fact about “an unsentimental audit of Indian foreign policy.” Significant sections are dedicated to bitterly criticizing the legacies of the Nehruvian approach to China through the “Bandung spirit” of the 1955 Asia-Africa Conference along anti-colonial and ‘third world’ solidarity lines. Most notably, the fallout and lessons from the 1962 India-China War loom large in Jaishankar’s thinking on how India should approach present and future China, guided less by idealistic ideologies and more by an upfront, unsentimental, and power-seeking realism. Affectionally, “India truly believed in its relationship with China” along de-colonial fraternity lines until 1962, with the border war having left many ordinary Indian citizens and Nehru personally shaken until his death.

In Vietnam’s present psyche, its memories and lessons from the 1979-89 war with China also loom large, as part of its lingering trauma from the fallout of its once radical commitment to socialist-internationalist solidarity by the end of the Cold War. Besides the geopolitical implications of the 1979-89 war in Asia, the most painful implications for Vietnam were perhaps manifested in terms of (un)affectionate politics: the war had been preceded by China’s enormous political, diplomatic, military, humanitarian, and cultural assistance during Vietnam’s wars against France (1946-1954), the United States (1965-73), and the early formation of the Vietnamese Communist Party since 1925, and culminated most intensively unsentimentally by China’s labelling of the newly reunified and destitute Vietnam as an “ungrateful country.”

Forty-five years later, large scars in many people’s hearts remain untreated from this war, especially among those who still affectionately remember a different and bygone “new China”. Isolated and pressured simultaneously by the West and China, it is no wonder that Moscow’s support was overall appreciated despite its own limitations, which after 1991 propelled both India and Vietnam to de-ideologise and expand their foreign relations with much of the world.

Unlike during the Cold War, India and Vietnam today are no longer on the receiving end as the US-China competition rages: if China’s economic rise from the 1980s was geopolitically propelled by its daring pursuit of a united front against the USSR together with the US, its place has now been replaced by India and Vietnam’s unreluctant drive to propel their own, long-awaited economic modernisations from this new competition. Against this background, or in the words of Jaishankar, “a difficult history yet to be honestly confronted”, past and present cosmopolitan visions for rejuvenating “decolonial solidarity” along the Bandung spirit or “Asia for Asians” (proposed by Xi Jinping in 2014) are unlikely to gain any serious political and affectionate momentum in this century.

India and Vietnam’s approaches to Russia are, therefore, not merely underpinned by politics as a professionalised affair of crude judgements of temporary costs and benefits but also as a matter of involving long-time cultivated and deeply-held morally and personally-assessed sentiments, and how such sentiments in turn should influence the decision-making processes on treating Russia. In addition, perhaps to a lesser extent in India, Vietnam’s approach to Russia remains partly shaped by an enduring worldview that the first Cold War has yet to end concerning regime survival. Vietnam’s treatment of today’s Russia as the predominant heir of the USSR has enabled the latter a prolonged and dishonest prestige in terms of informal reciprocal support. Regardless, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine remains legally and morally wrong and cannot be excused for past deeds. Seeking an alternative world order, a different model of socio-economic prosperity and freedom, begins at home. Overseas warfares merely unmask one’s impoverished vision for a multipolar world that is genuinely more democratic, egalitarian, and just in policy substance beyond symbolism.

In other words, affectionate feelings towards any country held by leaders, civil servants, and citizens matter, even as they are surely overshadowed by serious realpolitik and the stigmatisation of high emotions during decision-making processes. Affections are harder to alter and change than policy, but they’re deeply related. The role of affectionate politics and their potential transformation may provide an insightful outlook into a new world and century that is increasingly about Asia, especially India and Vietnam.

Chelsea Ngoc Minh Nguyen worked at the UN in Indonesia (including East Timor) between 2019-2022 and Thailand between 2016-2017. She tweets @CNguyenEc. Views are personal.

(Edited by Prashant)

Nice argument. But pragmatism & adjustment to current realities are also evolving features of diplomacy