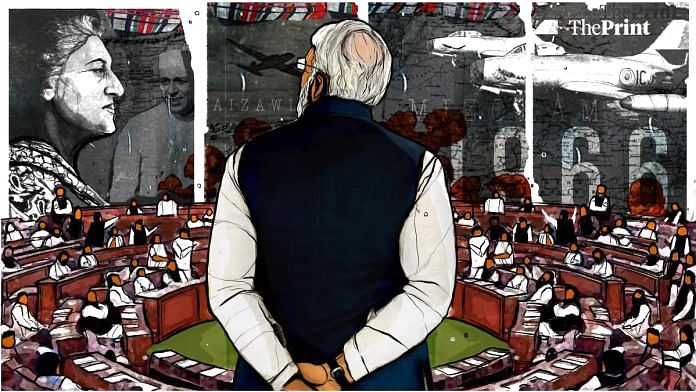

In his reply to the no-confidence motion earlier this week, Prime Minister Narendra Modi brought back two vital, contentious and tragic turning points in India’s national security history.

The first, in March 1966, was the use of IAF aircraft to strafe Aizawl — then a district headquarters and now capital of Mizoram — to drive out insurgents. And the second, Operation Blue Star, which resulted in the destruction of the Akal Takht, the seat of Sikh spiritual and temporal power located in the Golden Temple complex.

It is hard politics, and the prime minister is within his rights to employ arguments and slices of history that he thinks make his case best. Even those that make him sound more like the liberals that his party doesn’t particularly admire, especially on national security issues.

Nevertheless, it gives us an opportunity to raise and explore one of the oldest questions in our national security debate: Which was the most dangerous decade for India since Independence? The competition for the worst or most perilous 10 years has always been between the 1960s and the 1980s. The Mizoram air raids marked the first, and Operation Blue Star the second.

My choice for the most troubled decade has always been the 1960s. A caveat is in order, though. Nobody can understate the perils of the 1980s, which the generations up to the Millennials have lived through. There was the radical insurgency in Punjab, the return of terror in Kashmir, killings of Hindus in both states, Operation Blue Star, mutinies in the Army’s Sikh units, massacres of Sikhs in Delhi and elsewhere, the Bhopal gas disaster, a near-war with Pakistan over Exercise Brasstacks, a rough stand-off with the Chinese over Sumdorong Chu that took almost a decade to resolve, IPKF operations in Sri Lanka and unstable internal politics, especially post-Bofors.

Things were, however, so much rougher for a much, much weaker India in the 1960s that those 10 years must be the most touch-and-go in our independent history. The sudden rise of the Mizo insurgency exactly halfway through that tumultuous decade came at the worst possible time, even in a true crisis epoch.

Lal Bahadur Shastri died in Tashkent in January, 1966. Indira Gandhi took over as an inexperienced and unprepared prime minister, India had fought an economically withering war with Pakistan just six months earlier, and the Mizo National Front proclaimed sovereignty. There were less than three months between Shastri’s death on 11 January and 6 March, when the rebels were hurling assaults on the Assam Rifles battalion headquarters in Aizawl.

What followed, and the use of air power, is something we discussed in this earlier article and #CutTheClutter episode, and you can read more in this explainer by Ananya Bhardwaj. So we are not going there again. We will, on the other hand, be going back and forth, surveying that period. Because there lie many lessons not just on national security, but also on how our leaders handle these. And on how critical internal politics is to national security, stability and cohesion.

Also Read: Time for Modi to learn from Indira Gandhi. Biren govt is problem, not solution in Manipur

The country, borders and neighbours that Jawaharlal Nehru’s government had inherited from the British were unsettled and menacing. While Pakistan was already a military enemy from 1947, China had begun to loom on the strategic horizon within a decade. By the mid-1950s, the Naga insurgency had begun. If anything, Nehru had taken too long to send in the Army, in the hope that talks would settle the issue. That’s how, generally, the crisis was allowed to fester in the 1947-52 period.

By 1957, the fight was on, and in fact, the first concerted effort to resettle tribal people from distant and isolated hamlets into “secure” villages close to Army units had begun. This was the original atrocity in the name of creating “Protected and Progressive Villages” (PPVs). Terrible excesses and human rights abuses occurred, although the order of the day issued by then Chief of the Army Staff said exactly the opposite: They are our own people etc.

As the relationship with the Chinese deteriorated, the Dalai Lama escaped to India, Beijing became a patron of the Naga rebellion, and the first armed clash took place between Indian troops (CRPF) and the Chinese PLA on 21 October, 1959 in Hot Springs — exactly the region that is “hot” in Eastern Ladakh today. That set up the decade that was to come.

We can look at each year by turn. In 1960, Naga rebels and the Army were fighting a full guerilla war, and its peak of sorts was the shooting down of an IAF Dakota dropping supplies to an Assam Rifles unit that was under siege and in danger of being overrun by the guerillas in the village of Purr. The pilots made a crash landing in a paddy field in blinding rain, and were all taken captive.

While the five Army men in the back of the plane were released soon afterwards, the four IAF officers were held captive for 21 months. The Nagas held such sway that they were even able to smuggle a British journalist, Gavin Young of The Observer, into territory controlled by them to interview the crew led by Flt Lt A. S. Singha. A little factoid: Singha was the brother-in-law (wife’s brother) of actor Dev Anand.

Among those who were involved in the offensive air operations against Mizo rebels in these years were Suresh Kalmadi and the late Rajesh Pilot who were both IAF officers. Incidentally, both served in transport squadrons which were also used in an improvised combat role, both in March 1966 and later in the 1971 war. IAF was also heavily involved in chasing and blocking East Pakistan-based Mizo rebel leadership trying to escape to Burma.

With the Army already engaged in this brutal bush war and the Chinese danger rising, Nehru launched a three-service operation to liberate Goa in December next year. That accounts for 1961 in our chronology of a troubled decade. The war with the Chinese and the debacle marked 1962. Seeing India as defeated and weak, the Pakistanis were stirring up trouble in Kashmir now. So the so-called Hazratbal incident (the theft of the holy relic) put the Valley on edge in 1963. In 1964, Nehru died in harness with no succession planning.

Shastri took over as a compromise candidate, and we cannot forget that he faced three no-confidence options although he was in power for just about 19 months. The following year, 1965, saw the Kutch conflict in April; this was like a mere trailer of the bigger action ‘show’ that would unfold later in the year, the 22-day war that began in Kashmir and ended in Punjab.

Shastri died at the start of 1966. By this time, the Naga insurgency was at its peak, Mrs Gandhi was seen as weak and the Mizo insurgency had begun. There was much other trouble underlying the national crisis then. The Punjabi Suba movement always had a radical fringe. In 1966, a compromise was made and Punjab was split on a linguistic basis. But not before leaders like Master Tara Singh and Sant Fateh Singh (later Darshan Singh Pheruman) led multiple fasts and protests. It was also still the period when Dravidian politics had a strong separatist impulse. This was affirmed to me forthrightly by M.Karunanidhi in a Walk The Talk interview on NDTV. That changed by 1967.

Also Read: Manipur saw ‘free’ India’s 1st flag hoisted. Now it’s BJP’s biggest internal security challenge

All this was playing out in a decade of multiple famines, crop failures, and the humiliation of food aid through PL-480 with a mostly hostile America and an economic downslide. But 1967 brought no respite. It was a major skirmish with China in Nathula, and the bright spot was that the Indian Army got the better of them in those exchanges. In the general election that year, the Congress suffered heavy reverses, further weakening Mrs Gandhi and causing political uncertainty.

By the next year, a crisis was building in the Congress. Mrs Gandhi split it in 1969, took a heavy leftward shift and, in a way, provided a fitting end to that terrible decade. Of course, the crisis in Pakistani internal politics, the crackdown on its eastern wing, led India into another war just a year later.

That fraught era was marked by American political scientist Selig Harrison’s famous (or infamous?) India: The Most Dangerous Decades. In 1960, he gravely foresaw India being unable to withstand growing pressures, external and centrifugal, and breaking up. In the six decades since, we Indians have not only proved him entirely wrong, but grown stronger by the decade. Never mind the 1960s or the 1980s. And despite the many unfortunate turns like that 1966 March fortnight in Mizoram.

Addendum

The Prime Minister’s speech on the no-confidence motion has sparked a controversy and debate over the use of the IAF in offensive operations against Mizo rebels for about a week beginning 6 March, 1966.

The controversy is over whether late Rajesh Pilot, who became a Congress leader and MP subsequently, participated in the attacks as an IAF officer and pilot.

I have said so in some of my writings in the past.

In view of the fact — as demonstrated with documentation by Sachin Pilot — that his father was commissioned several months after the March 1966 Mizoram operations, it is evident that I got mixed up with dates and periods and erred in including his name. Accordingly, corrections are made in my archived article published originally in The Indian Express. You can read it here.

The mention I had made was based on several conversations over time with several members of the IAF pilot community of that era, including Rajesh Pilot. These showed IAF was used more than once against Mizo rebels. There were discussions in much detail since Rajesh Pilot flew transport aircraft and my question was, how could these carry out offensive/bombing missions? Rajesh Pilot was flying not a combat aircraft but a slow-moving, and small by the standards of transport aircraft, DHC-4 Caribous.

The answer was that the idea was not to necessarily strike any particular target, but to intimidate and scare the rebels. The method, therefore, was to load explosives in the cargo bay of these military transports and drop these in the general area where rebels might be hiding. Or trying to escape.

In the 1971 Bangladesh liberation war, for example, the IAF was active over Chittagong Hill Tracts, as Mizo rebels, including its top leaders, then harboured in East Pakistan, were fleeing to Burma. These operations are documented in some key books and accounts of that war.

Sachin Pilot confirms his father was involved in air attack/bombing missions in the 1971 war. I have obviously mixed up the dates and periods from our many conversations which I regret and stand corrected. The basic facts of the operations, offensive use of transport squadrons where Pilot served against Mizo rebels stand.

That said: It is unfortunate if armed forces’ operations ordered by the government of the day are personalised, especially if it demonises individuals in uniform for merely carrying out their orders. That’s what honourable professional soldiers are expected to do.

India has a long history of deploying the armed forces to fight multiple internal rebellions. These soldiers were following the orders and putting their lives on the line to protect their nation. For decades, through all governments — including the current one — Indian armed forces personnel have been conferred gallantry awards for fighting domestic rebels. These also include several Ashok Chakras, the highest gallantry award in internal operations. Gallantry awards have been won by many Army officers and other ranks involved in Operation Blue Star, which led to the unfortunate destruction of the holy Akal Takht, and which the prime minister also mentioned disapprovingly in his speech.

A point to note is that when the BJP first came to power in 2014, Sukhdev Singh Dhindsa, Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD) general secretary and former minister, demanded that the government withdraw all gallantry awards granted for Op Blue Star. The Modi government was wise to ignore it despite the fact that the SAD was then a stalwart NDA ally.

Professional soldiers act on the State’s orders, not on their individual views and choices. In the best of all worlds, however polarised our politics might be, that’s how it should always remain.