Is India a failed state? Certainly news magazine India Today thinks so. I would humbly disagree. We aren’t a failed state yet. For, if we were, the publication wouldn’t have said so on its cover, and I wouldn’t be writing this article.

If India was a failed state already, we might not have known how badly we were failing. As long as a nation’s own media, civil society, even individual citizens are free to bring the bad news to all, hold the mirror to the most powerful ruler in at least four decades, we are not a failed state yet.

What are we then? I might have a more apt description, a flailing state. Writhing in pain, tossing about in desperation, confused, chaotic, poorly-led, on the verge of a disaster. But still looking for answers.

Flailing state, therefore, is a better characterisation for India today, and it’s such a pity I didn’t invent it. It was economist Lant Pritchett, currently Research Director at Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford, in his much-quoted 2009 paper at Harvard’s Kennedy School, provocatively titled, ‘Is India a Flailing State: Detours on the four lane highway to modernisation’.

Important point is, he said this of India in 2009, when the UPA was in its prime and the growth still red hot on top of a breathless decade. What hadn’t caught up was the state capacity to improve governance, the quality of life of the vast majority of our people, and the ability to leverage growth into wider prosperity and social security.

Between 2009 and 2014, under a confused UPA-2, the quality of governance slid steeply. The government was paralysed with contradictions and indecision. As the state flailed even harder, Narendra Modi rose to seize the moment and promised to change it. Minimum government, maximum governance. People believed him.

Enough of an uncertain, dithering state, he promised in his new India. Through seven years of economic stall, his voters kept their faith in him. Until this virus came back and exposed the reality. That after seven years under Modi, India is an unprecedentedly dysfunctional, worse flailing state.

The ‘state’, top leadership, its institutions, including the bureaucracy and scientific establishment, are all either missing in action, or scurrying about to cover up, somehow airbrush the image, not alter reality.

Every leader has their key brand propositions. Modi’s, besides Hindutva and hard nationalism, included administrative ability, execution and efficient delivery of welfare. We’ve seen some of that in the past seven years, especially with distribution of welfare benefits to the poorest and the building of hard infrastructure. But, the foundations of basic governance were not strengthened.

Institutions were weakened, none more so than the Union Cabinet. If this functioned like a normal Cabinet institution, its most effective ministers would be put in charge of this crisis response. Those who failed on the job, would have been shown the door. In such a grave national crisis, you don’t put your politics ahead of the life-and-death issues.

Also Read: Mayday, Mayday — How Modi govt led India into a perfect storm

I know any mention of Jawaharlal Nehru is triggering for many. But after the debacle of 1962, he acknowledged failure, fired his defence minister V.K. Krishna Menon and brought in Y.B. Chavan. Soon enough, the Maratha strongman had initiated the Indian military’s first five-year modernisation plan. Results were visible in the 1965 war against Pakistan.

From Nehru, Lal Bahadur Shastri inherited a humiliating crisis of food shortages. He took it head on and brought in C. Subramaniam as agriculture minister, who Indira Gandhi continued with. By 1969, we had the Green Revolution.

If we find the Gandhi dynasty troubling, go back to the near-default level economic crisis of 1991. P.V. Narasimha Rao gave finance to then non-politician Manmohan Singh.

In the wake of 26/11 in 2008, Manmohan Singh got rid of his home minister Shivraj Patil and moved P. Chidambaram there. Institutions like the NIA and NTRO, which Modi government so values for multiple reasons, are all owed to him.

This isn’t a call to fire this minister or hire that. Personalities don’t matter. Issues do. Let’s therefore list the crucial ones that made these hard decisions possible.

*To begin with, there was honest acceptance that something had gone wrong. Unless you accept a failure, you cannot address it.

*There was no compulsion to ring-fence the top leader/leadership.

*There was no desperation to give all the credit to one leader. Because that requires a constant declaration of victory.

*At each of these junctures, there wasn’t an almighty cult of sycophancy. We know there was no Twitter then, but we had seen some phases of incredible sycophancy under Indira Gandhi. Since we began this article with an India Today cover headline, there was another in 1982: ‘Sycophancy Unleashed’. But we didn’t have ministers writing multiple tweets a day hailing the prime minister for every aircraft landing and disgorging foreign aid and presuming their job was done. Especially when the reason that aid was needed was their own failure with their portfolios.

The way they are getting away, and the prime minister has retreated, is adding to the disaster. It’s a government in denial. Its defence ranges from, our deaths are still much lower than Britain’s, to this is an awful, evil new variant you see. One call from our PM and more oxygen is landing. The latest is, the wave is plateauing and the crisis will be over soon. This is suspension of disbelief.

Also Read: As Modi govt faces up to Covid disaster, BJP learns a tough truth — the virus doesn’t vote

This collective denial and the inability of any institution to speak the truth has invited an unimaginable calamity upon us. It has greatly dented India’s global stature. Tens of thousands of Indians are dying every week in official figures (about 26,000 last week) and the graph is rising. Everything, from pathology labs to hospitals to crematoriums, is collapsing.

It’s time for some humility. Only that can lead to a larger national conciliation and a unity of purpose. What kind of humility? I am afraid I will invoke Nehru again, although there will be a probable consolation.

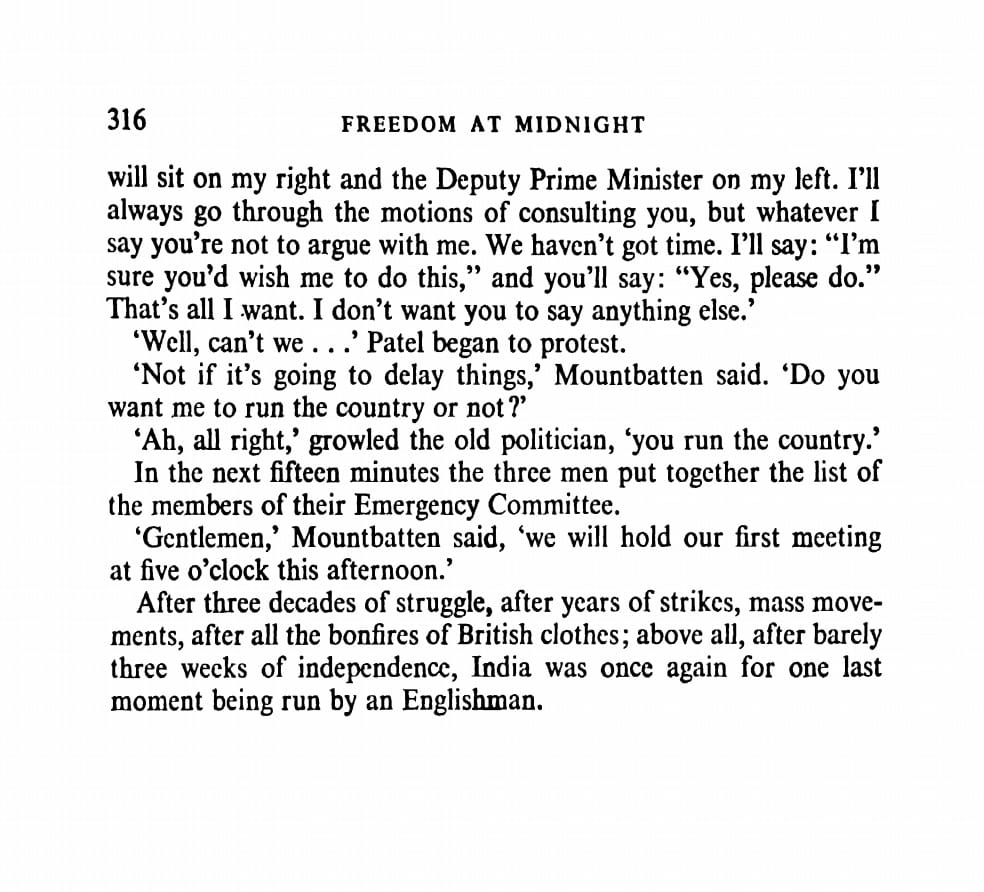

In their Freedom At Midnight, Dominique Lapierre and Larry Collins document a remarkable event. As Partition riots went out of control and the fire burning Punjab reached Delhi, Nehru met Viceroy Mountbatten, and asked for help. He, along with a key lieutenant, told him, they were not yet trained in governance, but agitation, and had spent years in their jails instead. They requested Mountbatten to constitute an emergency council and head it. The viceroy in charge, in a newly independent country.

This drew much protest from the Congress with demands to ban the book. But the authors noted this as an act of large-hearted statesmanship. We certainly do not suggest that Modi do any such thing. But, he needs to reach out to talent within his party and elsewhere, take the Opposition into confidence, build a joint federal front of the Centre and the states to douse this fire. All this will first need an acceptance of the enormity of the crisis, if not failure. It will need that one attribute we haven’t seen on display yet: Humility.

It won’t bring a dramatic solution. Because the problem of a flailing state is deeper and structural. Terrible stuff can visit nations, especially poor and populous ones. It’s how you respond that distinguishes a politician from a leader.

PostScript: Since we promised you a consolation of sort, the lieutenant accompanying Nehru in that meeting with Mountbatten was Sardar Patel. Read the pages from the book here.

Also Read: There’s a need to hold up a mirror to Modi govt on Covid management, and this is the picture