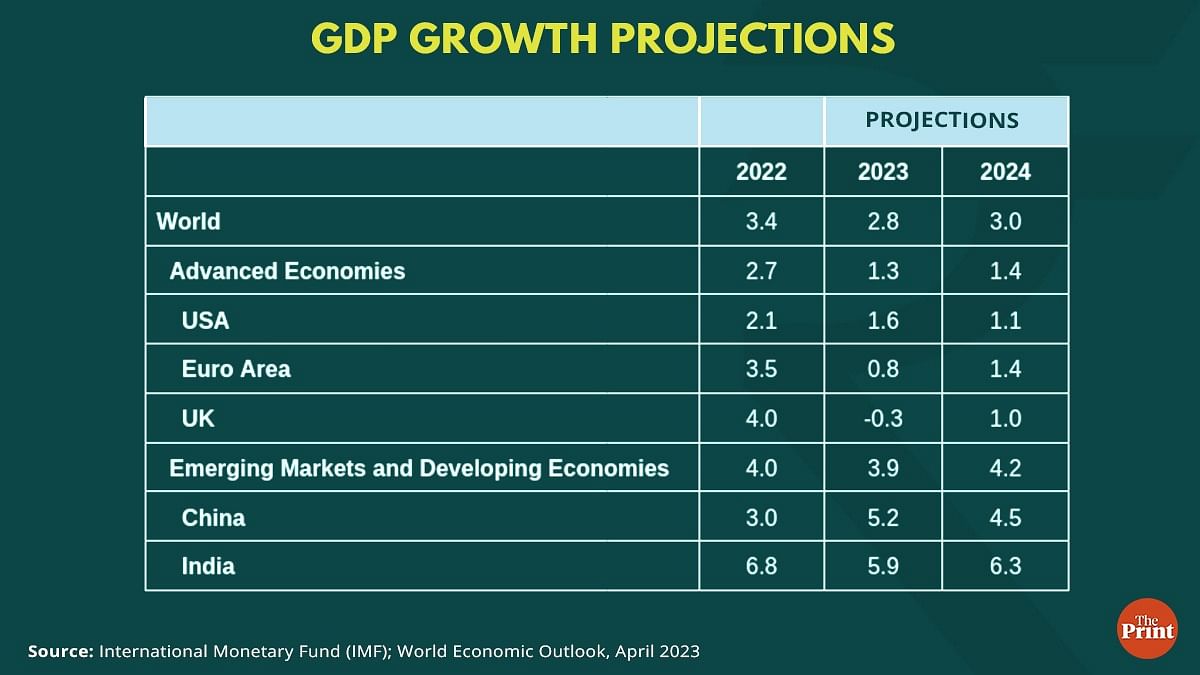

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) in its latest World Economic Outlook (WEO) has projected that growth globally and in India will slow down for 2023. Cumulative impact of adverse shocks, aggressive and synchronous monetary policy tightening will lead to a moderation in growth.

The recent episode of banking sector turmoil in the US and the European Union (EU) resulting in tightening of financial conditions could further hamper the growth prospects. Debt levels are likely to remain elevated. Debt restructuring initiatives need to be timely and should be accompanied with fiscal consolidation.

Growth projections: India and the world

According to the WEO, India will grow by 5.9 per cent in the current fiscal year. This is a downward revision of 20 basis points (0.2 per cent) from its growth forecast in January. Despite a significant reduction in growth estimates, from 6.8 per cent in 2022 to 5.9 per cent in 2023, India still continues to be the fastest growing economy in the world.

The IMF projects the global growth to fall to 2.8 per cent in 2023 from 3.4 per cent in 2022. Multiple shocks, such as the Covid-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, coupled with monetary policy tightening, have contributed to slowdown in growth.

This is more pronounced for the advanced economies.

Growth is projected to decline from 2.7 per cent in 2022 to 1.3 per cent in 2023. The WEO considers the recent episodes of financial sector stress and consequent reduction in lending as a downside risk to growth. The report cautions that due to a protracted period of low interest rates, financial institutions became complacent about valuation mismatches. The tightening of global financial conditions could result in further decline in global output.

Large swings in debt to GDP ratios

One of the chapters of the report is devoted to a discussion on the soaring debt profiles of economies in recent years. Covid-19 pandemic led to a massive surge in public debt. As a result of contraction in GDP and spurt in government spending, public debt as a share of GDP soared to 100 per cent in 2020. Rise in nominal GDP and inflation led to a decline in the debt ratio to 92 per cent by the end of 2022. Increase in revenues also led to reduction in public debt to GDP ratio.

The Fiscal Monitor of the IMF cautions that in 2023, deficits and debt are likely to rise due to slowdown in growth and rise in interest rates.

In India, for instance, according to the IMF, the general government debt surged to 88.5 per cent of GDP in 2020 from 75 per cent in 2019. This fell to 83.1 per cent in 2022. However, the pace of moderation is likely to be gradual from hereon for the next five years. Debt to GDP ratio is likely to remain above 83 per cent till 2028. For emerging markets, excluding China, too, debt as percentage of GDP is likely to remain elevated. Interest payments as a share of revenues are likely to remain higher in emerging and developing economies. Fiscal consolidation, along with targeted support to the vulnerable groups, is needed to bring down debt levels.

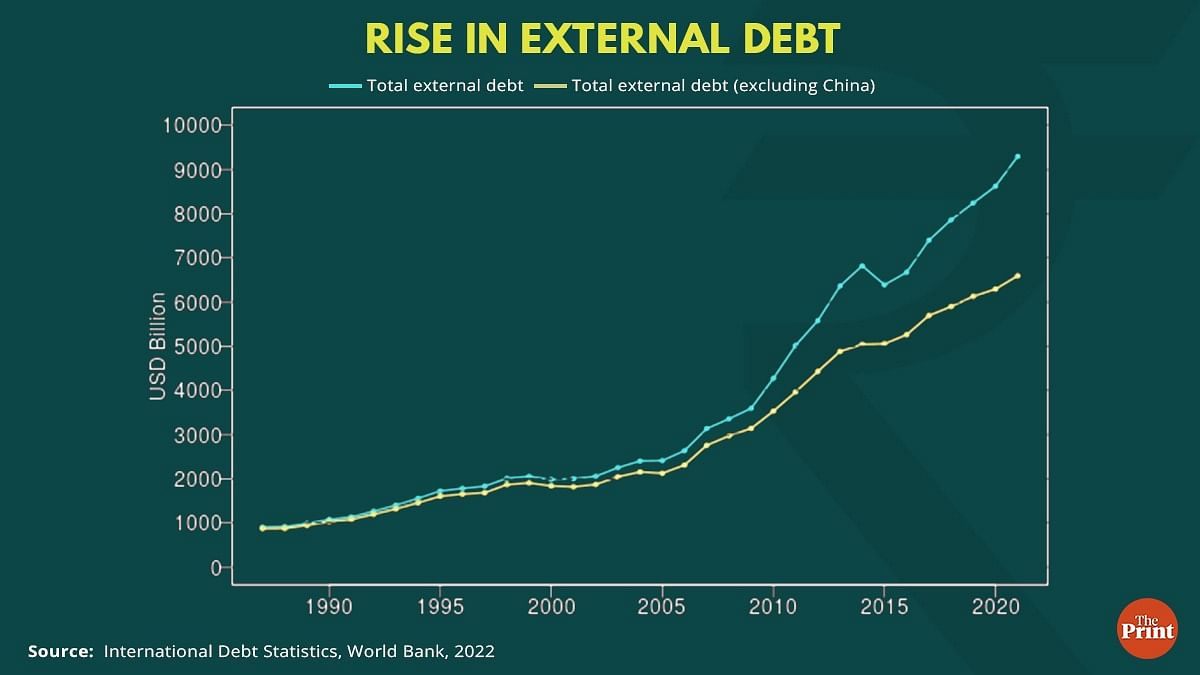

External debt overhang

The external indebtedness of countries, particularly low- and middle-income countries, rose to unprecedented levels during the pandemic. According to the World Bank’s International Debt Statistics, at the end of 2021, low- and middle-income countries held USD 9 trillion in outstanding external debt.

Creditors of debt can be official or private. Official creditors include Paris Club countries, non–Paris Club G20 creditors (for example, China, India, and South Africa), and other official creditors. Private creditors can be external or domestic residents. Notably, there has been a change in the creditor composition of external debt. Private creditors account now for an increasing share of low- and middle-income countries’ external debt, driven by growing appetite for high-yielding bonds issued by these countries.

Debt restructuring initiatives

The onset of the pandemic, supply chain disruptions and rise in food and energy prices raised the import bill and led to debt distress for a number of countries. In May 2020, till December 2021, the G-20 set up the Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) to help countries concentrate their resources on fighting the pandemic. Of 73 countries, 48 participated in the initiative which involved suspension of debt-service payments.

The DSSI gave way to the setting up of the G20 Common Framework — an agreement between the G-20 and the Paris Club to coordinate on debt treatments for low-income countries.

India under its G-20 Presidency has been pushing a concerted agenda to address the growing debt distress across the globe. India has been urging the G-20 countries to come together to address the debt distress of middle-income countries as well. The debt restructuring initiatives should be extended to middle-income countries also.

Recently, Sri Lanka received a USD 3 billion bailout package from the IMF after its bilateral creditors issued guarantees. Commitments from bilateral creditors to provide debt relief are often the first step to unlocking an IMF-backed restructuring programme.

There is a need for greater debt transparency, information-sharing and timeliness of the debt restructuring process. Debt restructuring by itself will not be enough. It needs to be followed with fiscal consolidation and growth enhancing measures to achieve a durable reduction in the debt-GDP ratio. Simultaneously, the multilateral financial institutions need to step up their funding to finance the emerging global challenges more effectively. In this context, the constitution of the G20 Expert Group on “Strengthening Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs)” is a welcome development.

Radhika Pandey is Senior Fellow at National Institute of Public Finance and Policy.

Views are personal.

Also read: How India can reverse investment slowdown and save the 2020s from being a ‘lost’ decade