A recent World Bank publication flagged a global economic slowdown in the 2020s that would usher in a “lost decade” for the global economy if bold initiatives are not taken to reverse the slowdown. The average potential GDP growth — the highest long-term rate at which the global economy can grow without triggering inflation — is likely to drop to 2.2 per cent in 2022-2030, from 2.6 per cent in 2011-21.

Policies towards promoting investment, improved human capital and faster labour supply could reverse the slowdown in structural growth. In India, the report points to the decline in investment growth from 2000-2010 to 2011-2021. While the reform initiatives announced by the government are in the right direction, they need to be accelerated to step up the rate of investment.

Assessment of potential growth

The report provides a comprehensive assessment of potential growth across advanced and emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs). There are three measures of estimating potential growth — the production function approach; univariate and multivariate filters; and long-term growth forecasts.

The production function approach represents output as a function of labour, capital and technological changes measured by total factor productivity (TFP). These are seen to be the fundamental drivers of potential growth.

Filters help to distinguish short-run deviations of output from trends. A series of filters are used to disentangle the short-run fluctuations from the long-run trend. Long-term growth forecasts, such as on a five-year horizon, present a picture of growth of the economy after stripping off the short-term fluctuations.

Regardless of the approach, the report shows that the potential growth in 2011-21 was below its 2000-2010 average for most of the advanced and emerging economies. The drivers of potential growth — labour force, investment, and TFP growth — slowed in 2011-21. Recessions following the global financial crisis and Covid-19 also accentuated the slowdown in potential growth in 2011-2021.

Also read: Amid US banking crisis, why central banks’ decision to prioritise price stability is the right move

Investment slowdown in India

In the case of India, estimates of potential growth are in the range of 6-8 per cent. However, according to the report, investment growth, a key driver of potential growth, has slowed from an annual average of 10.5 per cent in 2000-10 to 5.7 per cent in 2011-21. Poor infrastructure and burdensome administrative requirements leading to delayed project approvals and implementation are some of the factors that led to investment slowdown.

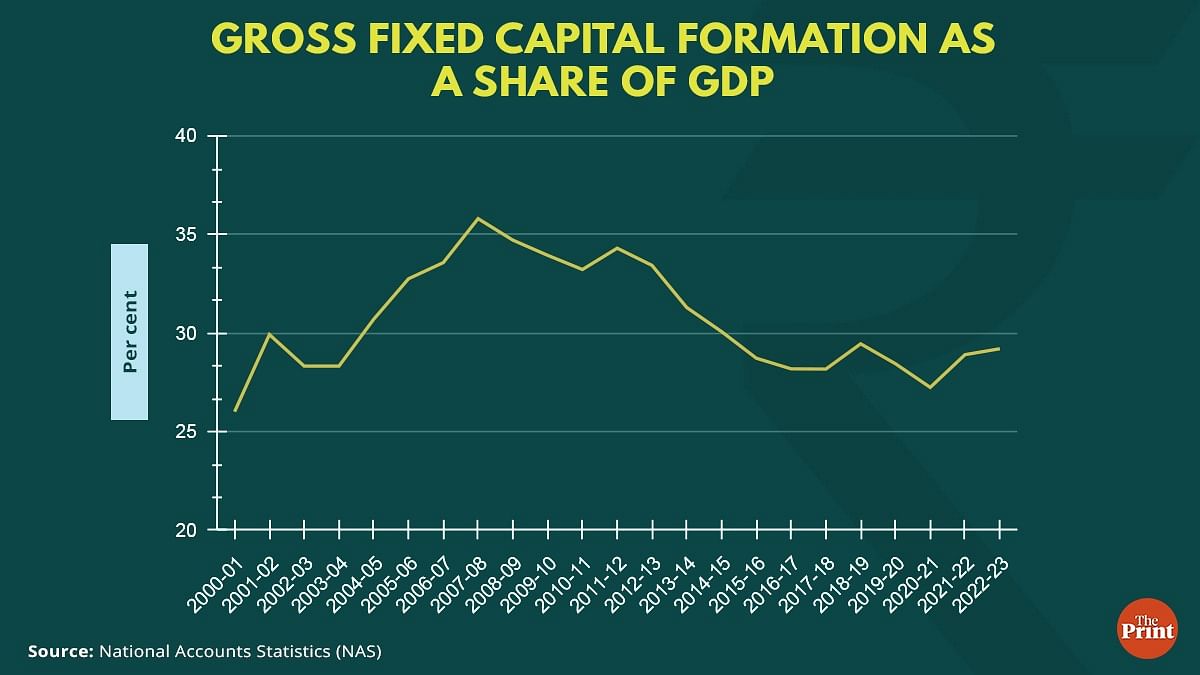

The investment rate measured by gross fixed capital formation to GDP peaked in 2011-12 and has since seen a moderation.

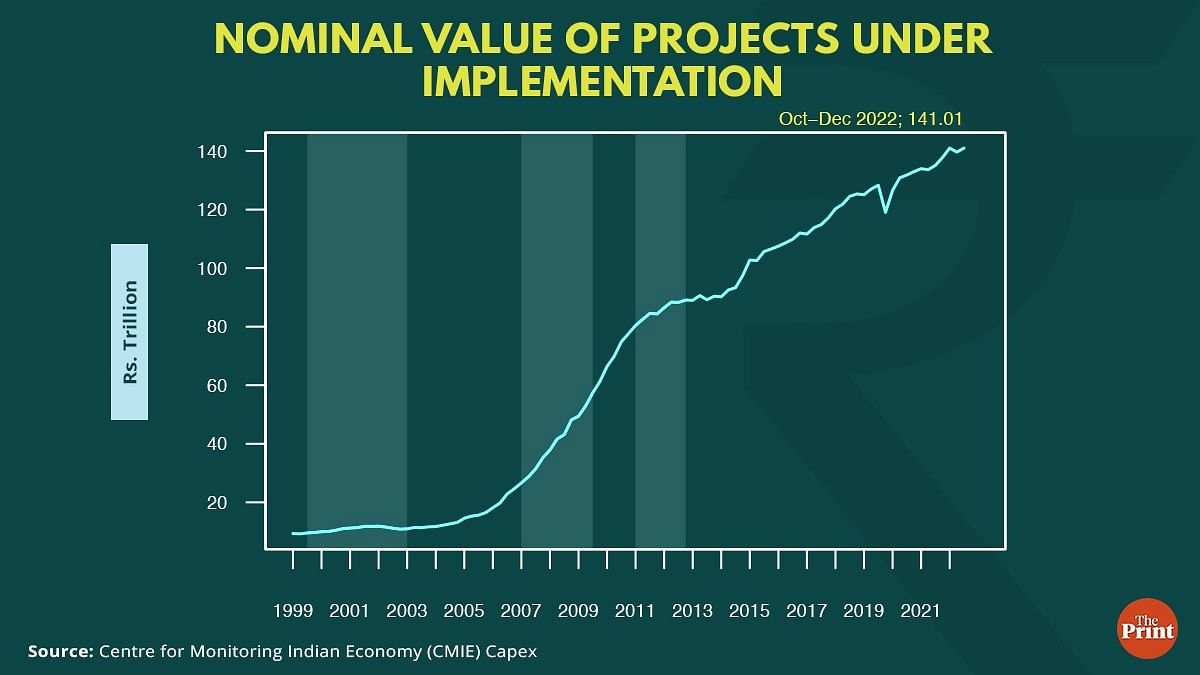

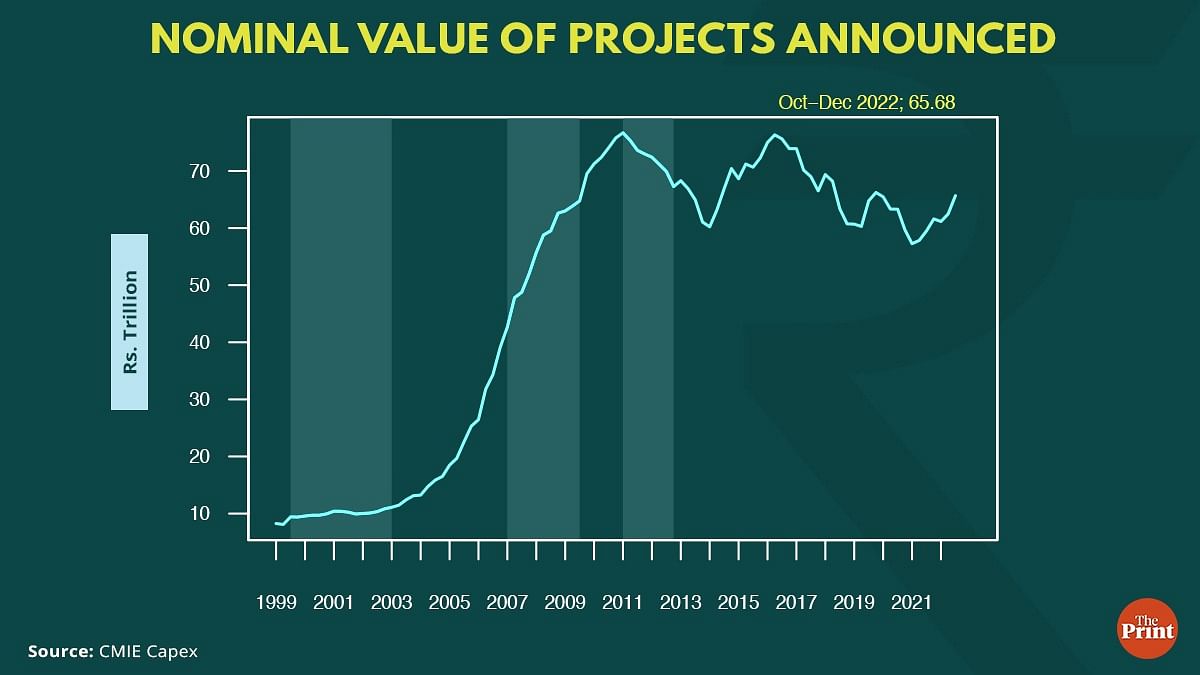

Another approach to assess the state of investment in the economy is to look at project-level data from the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) Capex database. Figure below shows the nominal value of projects under implementation. In the years 2005 to 2009, there was a sharp increase in the value of projects under implementation. But from 2012, the growth in value of projects under implementation slowed. The number of projects announced also saw a steep surge till 2011. Since 2012, the growth has not been sustained. The last few quarters have, however, seen an improvement in the value of projects announced.

The investment slowdown can be traced to the strategy of bank-led financing of infrastructure projects followed in the early 2000s. During 2003-08, bank credit saw a phenomenal growth of almost 40 per cent. The global financial crisis and the recession in the economy made repayments of loans difficult. The period following this saw a spurt in NPAs. Bank loans were stuck, resulting in the decline in the growth of bank credit.

Deleveraging cycle and repair of balance-sheets

One of the fallouts of the pandemic was the phenomenon of deleveraging (repaying loans) in the corporate sector. As investment activity slowed down amid an uncertain environment, many companies started reporting a reduction in their outstanding debt.

Even before the pandemic, the tendency to deleverage got a push post the Asset Quality Review (AQR) in 2015-16. The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) conducted an AQR with a view to cleaning up the balance sheets of banks.

Banks were nudged to recognise non-performing assets (NPAs) on their balance sheets.

An outcome of this was that banks came under pressure due to the ballooning of NPAs. Several companies were taken to bankruptcy courts by banks for failing to pay their debt. As an outcome, companies thought it prudent to repay debt and avoid debt-fuelled growth. The deleveraging cycle helped in repairing the balance-sheets of banks and corporates.

While the Covid year saw a contraction in investment, the following year saw a sharp rebound.

Reform push to boost investment

The World Bank report has acknowledged that by boosting public investment at a time when private sector investment was anaemic, the government has played an important counter-cyclical role. The government has undertaken a series of initiatives to boost investment. These include focus on infrastructure investment, consolidation of labour regulations, privatisation of underperforming state-owned assets and modernisation of the logistics sector. These need to be accelerated and bottlenecks need to be addressed.

The government launched the National Infrastructure Pipeline (NIP) with projected infrastructure investment of Rs 111 lakh crore. While 44 per cent of investment is expected to be funded through central and state budgets, the National Bank for Financing Infrastructure and Development (NaBFID), a development finance institution (DFI) set up to support long-term infrastructure financing, is equally important.

NaBFID plans to raise Rs 5,000 crore through bonds in the first quarter of the next financial year. The ability to raise finance requires a vibrant, liquid and efficient market for bonds. The size of the corporate bond market in India is small as compared to other emerging markets such as Malaysia, Korea and China. The market is characterised by limited liquidity in lower rated bonds. The market is dominated by private placements. The Budgets of the last few years have outlined steps to enhance the liquidity of the corporate bond market but implementation is the key.

The budget of 2021 announced its vision and strategy for the monetisation of government assets to generate additional finance to spur investment in infrastructure creation. The National Monetisation Pipeline aims at monetisation of the government’s brownfield assets. The target is to raise Rs 6 lakh crore from FY 2022 to FY 2026 which amounts to about 5.4 per cent of the total infrastructure investment envisaged under the NIP.

While the target for the last year was met, there are indications that the government may not be able to meet the monetisation target for the current financial year. Technical expertise for monetisation and building trust in Public Private Partnerships through transparency and contract enforcement will encourage a more active participation by private sector players.

Exit mechanism for zombie firms — those unable to repay interest obligations from their profits — could free up capital for more efficient uses.

Radhika Pandey is Senior Fellow at National Institute of Public Finance and Policy.

Views are personal.

Also read: Why India need not worry about Silicon Valley Bank’s collapse, but must learn from it