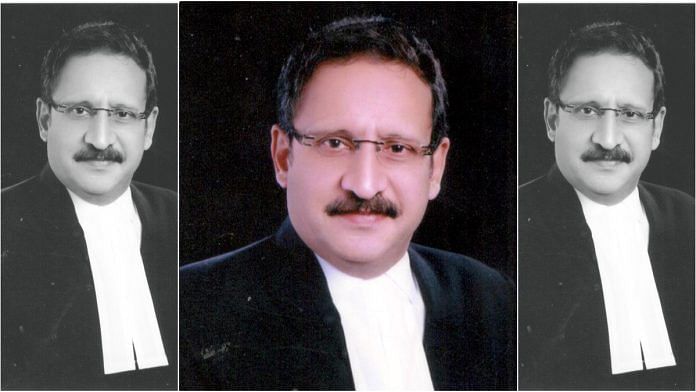

New Delhi: Allahabad High Court chief justice Pritinker Diwaker caused a storm Tuesday when he said that his transfer from the Chhattisgarh High Court by the SC Collegium led by then CJI Dipak Misra in 2018 was “ill-intended” and meant to “harass” him.

“My transfer order seems to have been issued with an ill intention to harass me,” Justice Diwaker said adding “however, as fortune would have it, the bane turned into boon for me because I received immeasurable love and support and cooperation from my companion judges as well as from the members of the bar.”

Describing his transfer as a sudden turn of events, the outgoing chief justice said that he still doesn’t know the reasons for shower of this “extra affection” upon him by former CJI Misra.

While appointment of judges has often displayed a tug of war between the executive and the judiciary, judges speaking out publicly against their transfers has brought back the focus on judicial transfers now.

Earlier on Monday, Justice Bibek Chaudhuri of the Calcutta High Court drew parallels between the transfer of judges during the Emergency with the transfer of 24 judges by the Supreme Court collegium in August.

Justice Chaudhuri said that he accepted the transfer “without any remorse”, but at the same time, he said that he considers himself to have become a part of history.

“In 1975, during the Emergency, 16 judges of different high courts were transferred by the Executive decision in one go. After almost 48 years, 24 judges have been transferred from one high court to another by the Collegium of the Hon’ble Supreme Court in one go,” the judge explained in a farewell ceremony hosted by the Calcutta High Court to mark his transfer to Patna. “Therefore, I am one of the beginners of the change of shifting of power from the hands of the executive to the hands of the highest seat of the judiciary.”

Justice Chaudhuri referred to Article 222 of the Constitution, which talks about the transfer of high court judges, and said that the provisions of the article should be “used sparingly”.

He urged the listeners to consider his case, pointing out that he would be taking charge at the Patna High Court on 24 November, but would not be in a position to discharge his duties for a few more days as he will have to make arrangements for his family.

“It (not discharging duties for several days) might not have happened if I and all the transferred judges had the opportunity to work in their native place,” he added.

Also Read: On strike over transfer of armed forces tribunal judge, bar association may challenge it legally

Twenty-four transfers in one go

In August, the SC Collegium had recommended the transfer of 24 judges from high courts, despite several of them requesting it to reconsider the decision. As per the collegium resolutions, while a few judges requested the Collegium to rethink their transfers, others requested to be transferred to neighbouring states instead.

One of the judges, Justice Madhuresh Prasad of the Patna High Court conveyed his consent to the proposal for his transfer to the Calcutta High Court. However, he requested the collegium to take into consideration that his younger son’s final board examination is due in February 2024.

However, the collegium refused to retract any of the 24 proposed transfers. Justice Chaudhuri’s was one such recommendation made 11 August.

Article 222 provides for the transfer of a judge from one high court to any other high court. As per the Memorandum of Procedure (MOP) for appointment of HC judges, the consent of a judge for his first or subsequent transfer is not required. All transfers, it says, “are to be made in public interest i.e. for promoting better administration of justice throughout the country”, without defining further parameters for such transfers.

This has led to several transfers being controversial in the past. For instance, in September 2019, Chief Justice Vijaya K. Tahilramani of the Madras High Court resigned after the SC Collegium refused to reconsider its decision to transfer her to the Meghalaya High Court.

Two years on, the transfer of Justice Sanjib Banerjee from the Madras High Court to the Meghalaya High Court had drawn calls for a reconsideration of the proposal from various quarters.

The SC Collegium had recommended his transfer in September that year. In response, 31 senior counsels wrote a representation to the collegium asserting that the “constant transfers and postings have left the Madras High Court in a state of constant flux”.

The Madras Bar Association also expressed concern over the opaqueness surrounding the transfer of Justice Banerjee, as well as the transfer of Justice T. S. Sivagnanam to the Calcutta High Court. “The transfers are perceived to be in violation of MOP for transfer. Such transfers are perceived to be punitive and do not augur well for the independence of the judiciary,” it said.

Transfers have also been taken hard by the lawyers in the past. For instance, in July this year, lawyers abstained from work in the Delhi High Court following the high court bar association’s call for a “token protest” against the transfer of Justice Gaurang Kanth to the Calcutta High Court. The association asserted that the transfer would adversely impact justice dispensation because of the reduction in strength of judges in the high court.

‘Transfers languish on somebody’s desk’

Transfer of judges has also been a bone of contention between the executive and the judiciary. For instance, the transfer of Justice M.R. Shah, led to a former CJI lashing out in open court.

Justice Shah was first recommended for transfer from the Gujarat High Court to the Madhya Pradesh High Court in February 2016, by a collegium headed by former CJI T.S. Thakur.

However, the Modi government made no movement on the file, and didn’t even formally reject the recommendation. This led to a bench headed by Justice Thakur lashing out in open court over the “pendency of certain recommendations for transfer of judges to different high courts” in August 2016.

Thakur specifically referred to Justice Shah’s recommended transfer, saying “if this is the approach of the Union government, then we would have no option but to withdraw judicial work from these transferred judges”.

Then, in January 2017, a day before CJI Thakur’s retirement, a bench headed by him accused the Centre of letting transfers of chief justices and judges of various high courts “languish on somebody’s desk” for months on end.

The government eventually returned the file to the collegium in early 2017, after Thakur retired and Justice J.S. Khehar took over as the CJI.

Justice Shah continued to serve in Gujarat till July 2018 as the second senior-most judge, till a new collegium headed by then-CJI Dipak Misra recommended his appointment as the chief justice of the Patna High Court. In November 2018, Justice Shah was elevated to the Supreme Court from where he retired in May 2023.

(Edited by Tony Rai)