New Delhi: The Supreme Court Thursday reserved its decision on a six-decade-old question: is Aligarh Muslim University — one of India’s oldest and most prestigious seats of learning — a “minority” institution under the Indian Constitution?

A seven-judge bench of the apex court was hearing the university’s challenge to a 2006 Allahabad High Court ruling that denies it this status.

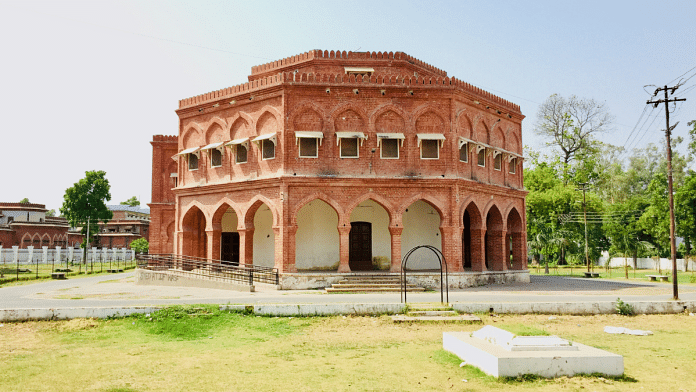

While doing so, the Supreme Court will also revisit its 1967 ruling in S. Azeez Basha and Another vs Union Of India — known simply as the Basha case. That ruling declares that the institution, which was founded as Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College in 1875 but eventually became a university by an act of parliament, is not a minority institution under Article 30 of the Constitution of India.

Under Article 30 (1), minorities are given special rights to establish and administer educational institutions. Article 30 (2), meanwhile, restricts the government from discriminating against minority institutions regardless of religion or language.

In 2005, the AMU implemented a reservation policy of 50 percent seats for Muslims in its postgraduate courses. This scheme was challenged in the Allahabad High Court, with non-Muslim petitioners arguing that the AMU was not a minority institution according to the court’s 1967 ruling and that it could not reserve seats.

Here’s a wrap-up of what the case is all about and what has happened in the Supreme Court so far.

Also Read: Nine-year-old Ashoka University is asking the most important question. Who am I?

History of the case

In its ruling in 1967, the Supreme Court held that AMU wasn’t a minority institution since it was neither established nor managed by Muslims. “It may be that the 1920 Act was passed as a result of the efforts of the Muslim minority. But that does not mean that the Aligarh University when it came into being under the 1920 Act was established by the Muslim minority,” the court had then said, even though it referred the question of what is a minority institution to a larger bench.

This ruling was met with protests, prompting Parliament to make amendments to the 1920 Aligarh Muslim University Act in 1981. The most significant among these amendments was the move to retrospectively redefine the word ‘university’ under the act to mean “the educational institution of their choice established by the Muslims of India, which originated as the Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College, Aligarh, and which was subsequently incorporated as the Aligarh Muslim University”.

The amendment also introduced a provision to specifically empower the AMU to promote the educational and cultural advancement of Muslims.

Meanwhile, reference from the Basha case was again taken up by an 11-judge bench in T.M.A. Pai Foundation & Others vs State Of Karnataka & Others.

However, even though the court decided the scope of the right of minorities to establish and administer educational institutions of their choice under Article 30(1), it failed to address the fundamental question of the criteria of what makes a minority institution.

In 2006, some non-Muslims challenged AMU’s 2005 reservation policy before the Allahabad High Court. In its ruling, the high court cited the Basha ruling to hold that the university wasn’t a minority institution. While doing so, it also nullified the 1981 amendment to the AMU Act.

It’s the challenge to this ruling that the Supreme Court is now hearing. Both AMU and the central government — then led by the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) — had challenged the decision in 2006. But in 2016, two years after the Narendra Modi-led National Democratic Alliance (NDA) was voted to power with a thumping majority, the central government withdrew from the case in 2016 and is currently opposing AMU’s appeal.

In 2019, a three-judge bench led by the then Chief Justice of India Ranjan Gogoi referred the case to a seven-judge bench, which will not only decide what makes a “minority institution” under Article 30 of the Constitution but also whether Parliament’s 1981 amendments to undo the Basha decision were correct in law.

‘Statutory recognition not enough’

Appearing for AMU during the SC hearings, senior advocate Rajeev Dhavan argued that merely because AMU has become a university through the 1920 legislation doesn’t mean that it loses its minority status.

Pointing to the existence of mosques on its campus and also to the fact that AMU’s highest decision-making body is mostly made up of Mulisms, he contended that the university retains its Islamic character despite having students from all communities.

In its arguments, AMU said that the Basha decision no longer held because it was superseded by cases such as TMA Pai, under which the court held that minority status cannot be taken away by mere legislative intervention.

On the other hand, Solicitor General Tushar Mehta, who argued for the Centre, said that the Basha ruling had correctly traced the minority status of the AMU.

For his arguments, he referred to a speech of M.C. Chagla, then education minister, eminent jurist, and former chief justice of Bombay High Court, in which the latter said the institution was “neither established nor administered by minorities”. Under the 1920 act, the erstwhile Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College had “surrendered” its minority status to the British government, Mehta argued before the court.

Administration of institution

On his part, senior Advocate Kapil Sibal, also appearing for the AMU, argued that an institution only needs to be “established” as a minority institution. “It is not essential that the institution be administered by a minority,” he argued.

Sibal’s submission was that the mere administration by a non-minority group would not mean that minorities have relinquished their control. Doing so would lead to Article 30 losing its very purpose, he argued.

“Might as well get rid of Article 30, why have it at all?” he asked.

To this, the Solicitor General said that the Lord Rector of the British ultimately controlled AMU and that even the university’s predominantly Muslim administrative bodies were answerable to the post.

Referring to the 1920 act, Mehta said there was never a mandate for AMU to be run by Muslims — it was primarily non-minority, and most people just “happened” to be Muslims, he argued.

Senior Advocate Neeraj Kishan Kaul, also appearing for the Centre, told the court that the Basha ruling had rightly declared AMU as a non-minority institution and that the 1981 amendment was incorrect in law because it ignored historical facts.

“By a legislative fiat or legal fiction you cannot take away a historical legislative fact, you cannot alter history,” he said. However, Chief Justice of India D.Y. Chadrachud intervened at this point to caution that such arguments could have “serious repercussions” on the law-making power of Parliament

Meanwhile, senior advocate Rakesh Dwivedi, who appeared for the non-Muslims who challenged AMU 2005 policy in Allahabad HC, suggested criteria for a “minority” institution. To establish this, it’s important to determine whether a community is numerically less than the majority and whether it recognises itself as a minority, he said.

“If the ruling group is numerically smaller, that does not qualify as a minority,” he told the court.

(Edited by Uttara Ramaswamy)

Also Read: This Indian watchdog is cleaning up ‘mess’ in academia—falsification, fabrication & fraud