New Delhi: There’s much to lament in India’s post-Covid job market, where recovery has been painfully slow. However, government data suggests that when it comes to the salaried sector, the participation of religious minorities — Muslims, Sikhs, and Christians, in that order — has been most gravely affected.

The Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation’s latest Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) — covering the period from July 2020 to June 2021 and released earlier this year — at least partly captures the impact of lockdowns, and their immediate aftermath, on salaried jobs across sectors.

The survey defines “regular/salaried employees” as “persons who worked in others’ farm or non-farm enterprises (both household and non-household)” and, in return, received salary or wages on a regular basis (i.e. not on the basis of daily or periodic renewal of work contracts). This category includes paid apprentices, both full-time and part-time.

According to the data, during 2020-21, the share of India’s salaried class in the workforce shrank by almost 2 percentage points. In 2019-20, about 23 per cent of the workforce earned a regular salary or wage, but in 2020-21, only 21 per cent did.

But to get a better idea of the effect of lockdowns, older data is instructive.

Since the survey is conducted between July and June every year, the 2019-20 survey includes values from the April-June 2020 quarter, when the most severe lockdown was in force.

In the year prior to that, the share of the salaried class in India’s labour force had actually risen by one percentage point, from 22.8 in 2017-18 to 23.8 in 2018-19. Hence, if we factor in all this data, it could be surmised that India’s salaried class has shrunk by 2.7 percentage points during the years that the economy reeled under the pandemic.

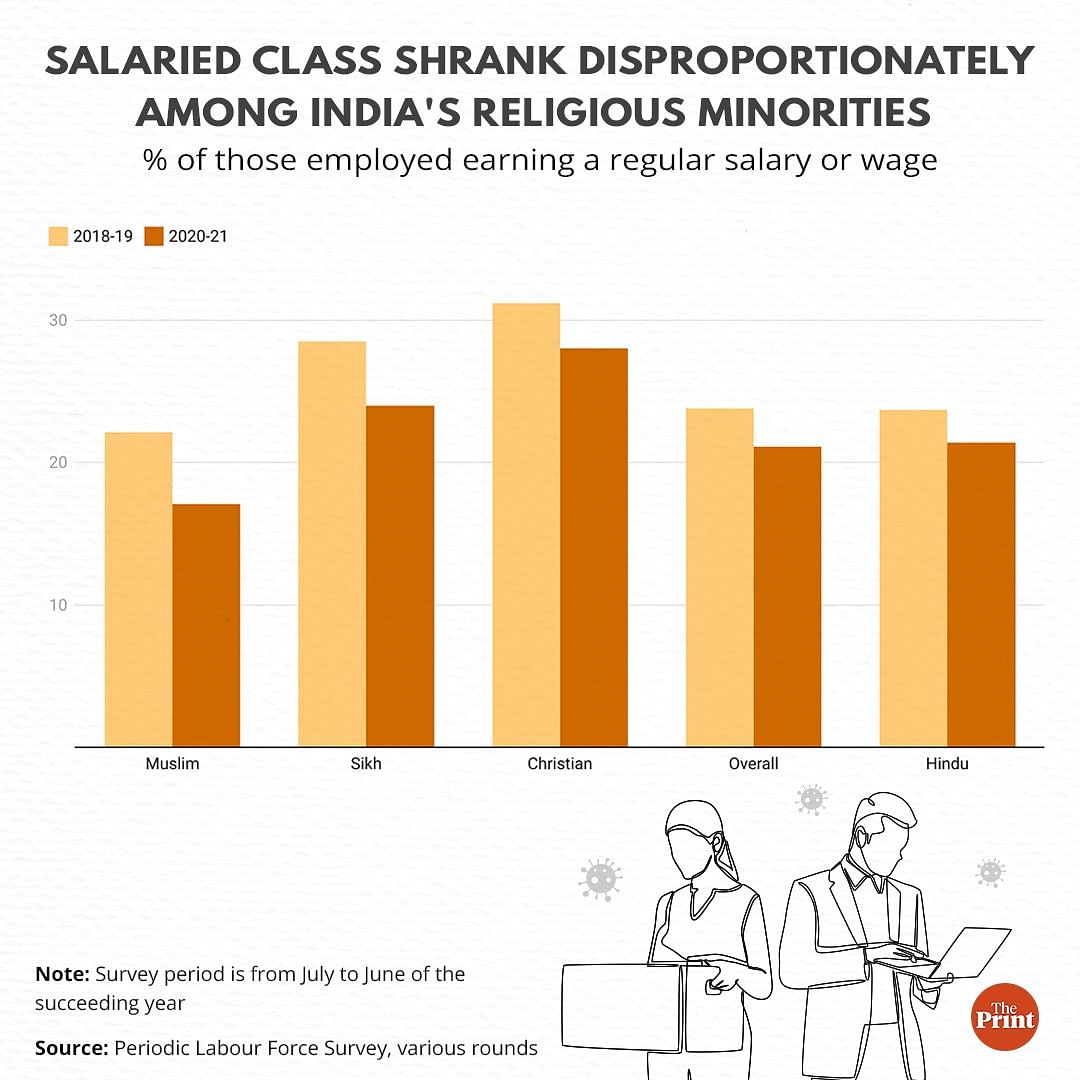

A closer look at the data, however, suggests that some religious minorities were disproportionately affected, with Muslims being most so.

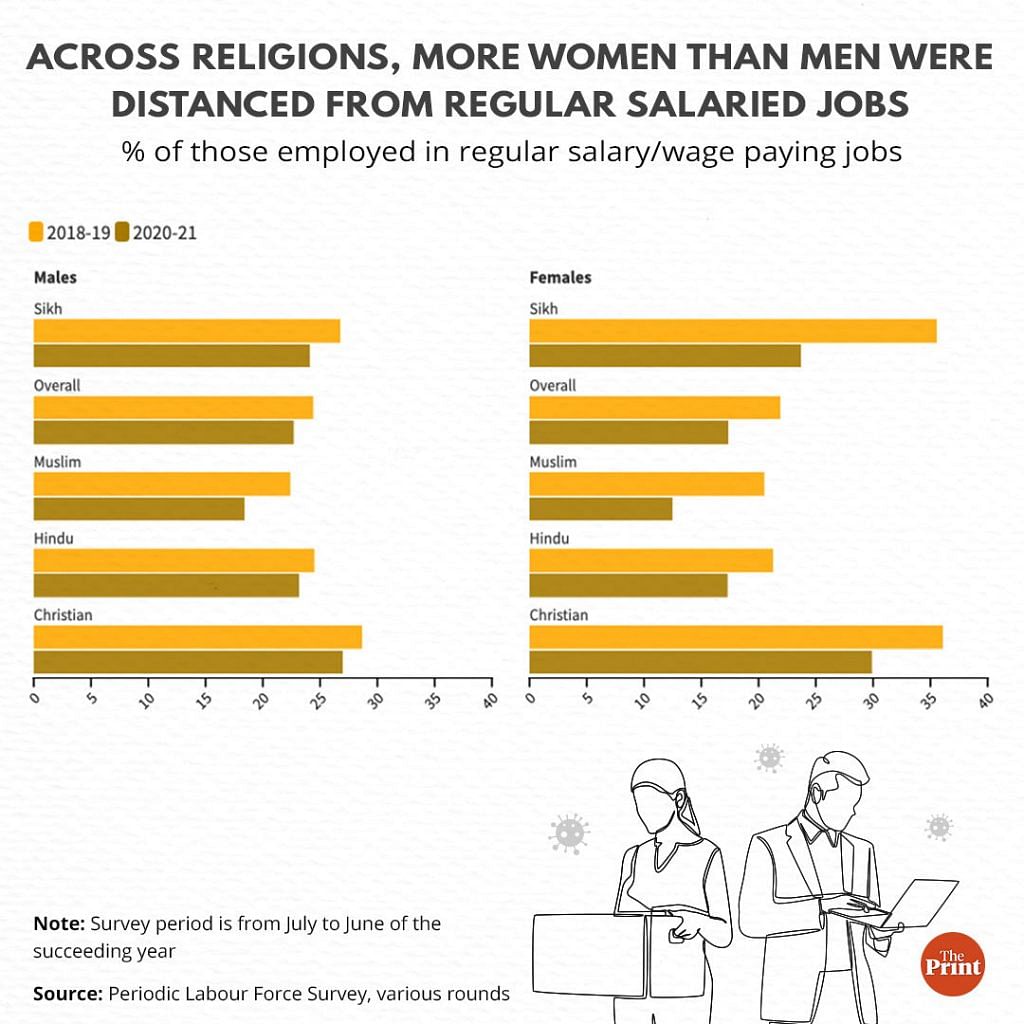

When gender is factored in, the picture grows even bleaker, with the data indicating that women’s participation in the salaried sector has witnessed significant declines across religions.

“India’s marginalised communities are most vulnerable to uncertainties — the pandemic has just proved that,” Archana Prasad, a professor at Jawaharlal Nehru University’s Centre for Informal Sector and Labour Studies, told ThePrint.

“Only those who had the opportunity to work from home and had access to the internet and other amenities survived the pandemic job crash. As a result, [people belonging to] marginalised communities were automatically pulled out from the formal sector and forced to look for work elsewhere to survive,” she said, adding that “discrimination” as a factor was also likely.

Further, Prasad also believes that the PLFS numbers misrepresent the actual employment landscape because its definition of the “salaried class” includes jobs that don’t offer social security (pension/ Provident Fund), paid leave, or written contracts. Many jobs that are counted as “salaried”, she argued, could come under the informal sector, which employs the most vulnerable sections of society.

Also read: Salaried jobs are hardly growing — govt data explains the Agnipath anger of young Indians

Muslims, women most affected

According to the survey, the share of Muslims who were earning a regular salary fell from 22.1 per cent in 2018-19 to 17.5 per cent in 2020-21— a drop of almost 5 percentage points. What this means is that for every 100 Muslims who were working, there were now five fewer among them doing a regular salary-paying job.

In the same period, the share of Sikhs employed in the salaried sector went down by 4.5 percentage points, from 28.5 per cent in 2018-19 to 24 per cent in 2020-21. For Christians, the drop was 3.2 percentage points, from 31.2 per cent to 28 per cent.

Compared to these minorities, Hindu workers in salaried jobs fared relatively better, with their share shrinking by ‘only’ 2.3 percentage points, from 23.7 in 2018-19 to 21.4 in 2020-21.

But the declining participation in the salaried sector is starkest among women, cutting across communities.

On average, the share of men in the salaried class dropped by about 1.7 percentage points (from 24.4 per cent in 2018-19 to 22.7 per cent in 2020-21), but the share of women fell by a much steeper 4.5 percentage points (from 21.9 per cent to 17.4 per cent).

This trend was pronounced among religious minorities, too.

The drop in the share of salaried Sikh men fell by 2.7 percentage points (from 26.8 per cent in 2018-19 to 24.1 percent in 2020-21), but for women it was by 12 percentage points (from 35.6 per cent to 23.7 per cent).

Among Muslims, the share of men earning a salary fell by 4 percentage points (from 22.4 per cent to 18.4 per cent), but for women, it was 8 percentage points (from 20.5 per cent to 12.5 per cent).

For Christians, the salaried class shrank by 1.7 percentage points for men (from 28.7 per cent to 27 percent) and by 6.2 percentage points for women (from 36.1 per cent to 29.9 per cent).

In 2018-19, about 21.3 per cent of the surveyed Hindu women had a salary/ wage-paying job, which dropped by four percentage points to 17.3 per cent by 2020-21. Hindu men, on the other hand, saw a mere 1.3 percentage point drop in the same period, from 24.5 per cent to 23.2 per cent.

Where did all the salaried workers go?

Many among those who left, or had no choice but to leave, salaried jobs became self-employed — either in their own enterprises or as “helpers in household enterprises”, the report said

In 2018-19, about 52.1 per cent of employed Indians were self-employed, and by 2020-21 the share of this category of workers had swollen to 55.6 per cent.

It should be noted, though, that the term “self-employed” here does not necessarily translate to entrepreneurship. Much of the gain in this sector is down to greater numbers of “helpers”, which the survey defines as those who work for a household enterprise but may not necessarily be given a wage (for instance, a son helping his father run a shop).

In 2018-19, the share of “own account workers” (self-employed workers who do not hire paid employees) formed 38.8 per cent of the employed workforce, falling slightly to 38.2 per cent by 2020-21. However, the helpers’ category accounted for 17.3 per cent of the workforce in 2020-21, up from only 13.3 per cent in 2018-19.

What experts say about Muslims’ employment

The shrinking of the salaried class among Muslims was the starkest across religius communities. While it is difficult to pinpoint why this is the case, some experts conjecture that this could be due to Muslims facing the first cut in an already stressed post-pandemic job market.

In an article for ThePrint in April 2020, Asim Ali, a researcher at the Centre for Policy Research, had argued that the pandemic worsened the well-documented economic marginalisation of Muslims in India — and especially so in the informal sector at a time when misinformation was being spread about how the community was supposedly perpetuating infections.

This year, too, there have also been a few calls for economic boycotts of Muslims, including a campaign targeting mango traders from the community, and another calling for a ban on them in temple fairs (both these instances were in Karnataka).

According to Prasad, it appears as if discriminatory attitudes towards Muslims have permeated most sectors. “This ideology is neither being countered by the political class nor by the business class. The discrimination in hiring has always been stark, but post pandemic, it has intensified,” she claimed.

Hilal Ahmed, associate professor at the Delhi-based Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS), said he had observed that amidst rising unemployment, many Muslims had moved out of the job market and back into the “traditional occupations” of their families.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

Also read: Indian start-ups have laid off 23,000 people since 2020. But here’s why there’s still hope