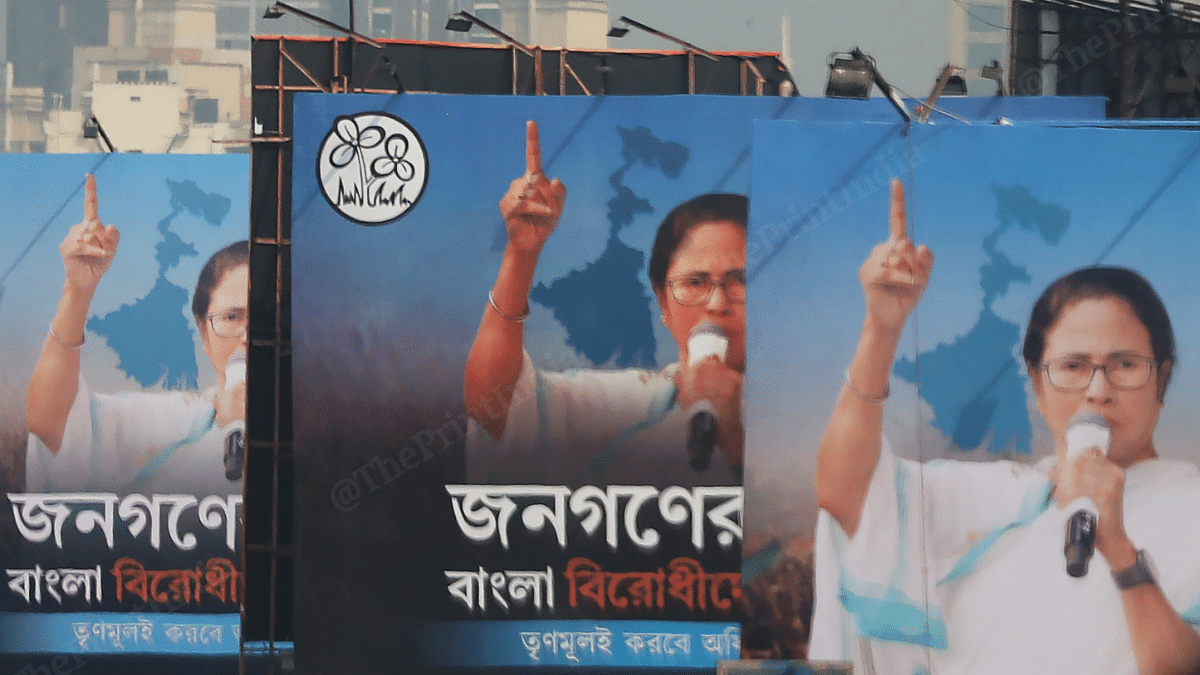

Kolkata/Birbhum: In 2019, West Bengal Chief Minister and Trinamool Congress (TMC) supremo Mamata Banerjee issued a fiat to the rank and file of her party: Return ‘cut money’ (euphemism for commission) taken from government schemes, or face jail.

Even the dead are not spared, Mamata said, referring to the ‘cut money’ taken for cremating the dead under a government scheme which provides money for last rites. “I do not want to keep thieves in my party.”

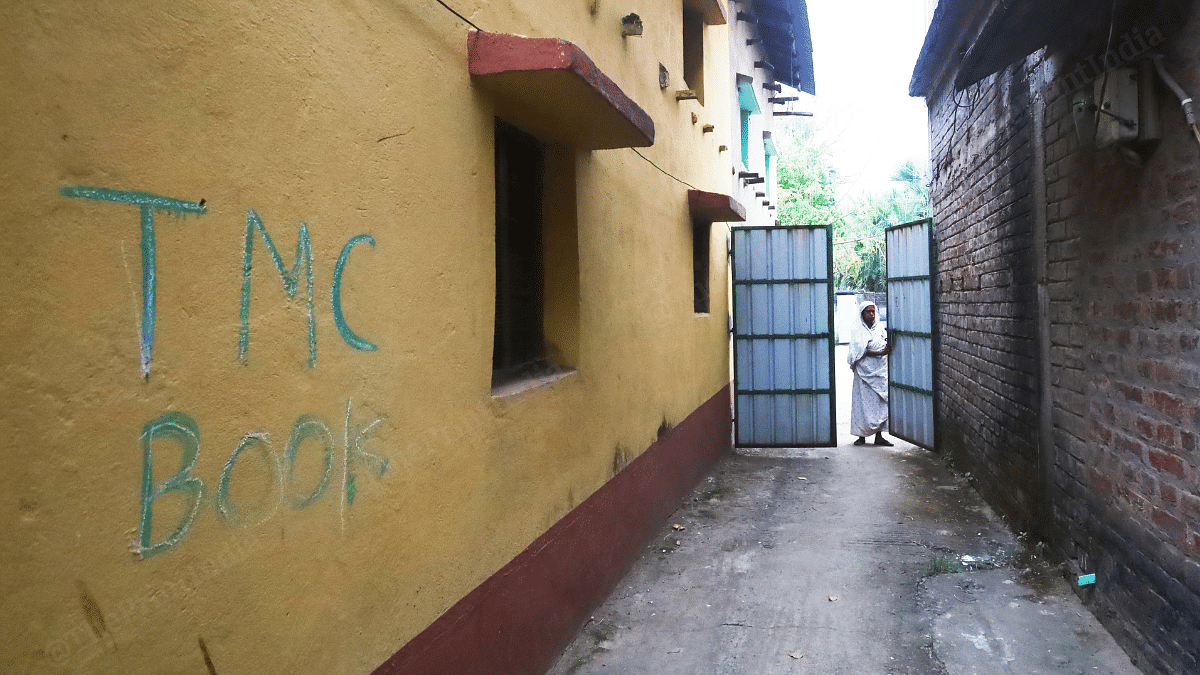

Soon, TMC leaders, especially at the lower rungs, across districts were attacked and gheraoed for returning money taken to implement welfare schemes. Several of them fled their villages.

Coming days after the Lok Sabha poll results were out, Mamata’s statement was strategic — a masterstroke, reportedly planned by political strategist Prashant Kishor, to distance herself from the deep-rooted extortion rampant in Bengal, and quell the brewing discontent among the masses. The plan succeeded, as the narrative of ‘cut money’ slowly dissipated.

Five years later with the Lok Sabha election just weeks away, the TMC is again in a spot. The grave allegations of land grab and sexual harassment in Sandeshkhali, a hitherto little-known, isolated island near the Bangladesh border, has come to haunt Mamata.

For the people of Bengal, Sandeshkhali is the embodiment of a political and economic system — fine-tuned under the TMC’s 13-year reign — marred by institutionalised corruption and criminalisation of politics, manifesting equally, albeit differently, across rural and urban areas.

As a Kolkata-based businessman says, the system of ‘tolabazi’ (party-led corruption) has been going on for generations — one that they have come to accept as part of the economic culture irrespective of which party is in power. “For us, it is like ‘jemon thakur, omni ful’ (roughly translates to each according to their own demands).”

The businessman’s sentiment is corroborated by academic literature, which popularly refers to West Bengal as a “party society”, where everything from government schemes to job allocations to organising Durga pujos to marriages is routed through party workers.

The ‘system’ in Birbhum

In 2022, when Trinamool’s Birbhum strongman Anubrata Mondal was arrested in connection with a multi-crore cattle smuggling racket, one of the first palpable changes witnessed by the villagers at Siuri was the closure of the “toll tax office”.

“Almost overnight, the toll tax offices disappeared,” a Siuri journalist says. “Every driver was expected to pay Rs 20 each time they crossed the toll booths…Nobody knew if those toll taxes were run by the government or not, but it was just accepted that one had to pay — nobody could question it.”

The “toll tax” was a symptom of the “system” run by the TMC district president, and in turn, the party in Birbhum.

“Nothing could happen in Birbhum without Mondal’s approval…He was like Birbhum’s Sheikh Shajahan,” says BJP state general secretary Jagannath Chattopadhyay. “The party, police, real estate, elections, government schemes, contracts — everything was controlled by him.”

In 2018, over 90 percent of the panchayat elections in Birbhum were won by the TMC uncontested. In 2023, the BJP and the Left-Congress alliance won six and two seats, respectively. “This was a big deal in Birbhum. Till the time Anubrata Mondal was there, this was unimaginable,” Chattopadhyay says.

Chattopadhyay’s claims are corroborated by people across Birbhum, who argue that the “system” has survived even after Mondal’s arrest.

“We pay extra money to TMC workers for everything — from ration scheme to housing scheme to making toilets,” says a local shopkeeper in a largely Muslim-dominated village at Mayureswar subdivision “My family paid Rs 20,000 to get money for the housing scheme. If we wouldn’t have paid, our next instalments would have been stopped. But there is a guarantee of delivery of schemes once you pay — that is true.”

His friend adds that he paid Rs 600 to get an LPG connection under the Ujjwala scheme as he was allegedly told that it was the cost of the connection.

“I later found out that this was free. They charged money from almost everyone in our village to get LPG connections,” he says. “We feel helpless, because everything is routed through TMC — if we oppose, it will be difficult to go about with day-to-day lives.”

From Ujwala and Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana to Swachh Bharat Mission-Gramin and Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS), “cut money” is demanded for the implementation of every scheme across villages, say local residents.

ThePrint came across several people who said that though the MGNREGS wages are transferred to their accounts, TMC leaders direct them to withdraw money from ATMs and give them their “cut”.

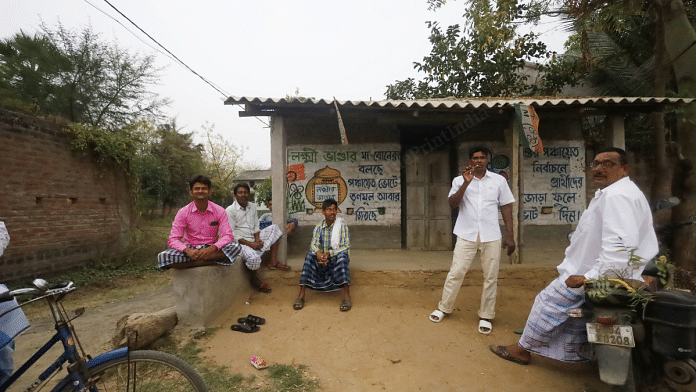

The grievances of Birbhum people — the control of local resources through panchayats, having to pay “cut money” for availing government schemes, allegations of rigged elections, and having a powerful local strongman — point towards a generalised pattern of the TMC rule in Bengal.

But to understand the “system” run by the Trinamool, it is crucial to understand its nuts and bolts, which came up in the Left Front’s 34-year regime in the state.

Also Read: West Bengal has a history of chit fund scams. No wonder Kolkata rules electoral bonds chart

How Left came to power

In 1965, when Singapore became an independent nation, its founding prime minister, Lee Kuan Yew, reportedly said that he wanted the city-state to be like Calcutta.

Calcutta was not just the political capital of British India until 1911. Until many decades later, it was also the financial capital — the trade volumes, for instance, were much higher than Bombay for most part until the mid-20th century. The Bank of Bengal was much larger than the Bank of Bombay for most part, and almost 45-50 percent of Indian companies were floated in Bengal until the early 20th century.

Yet, the economy of one of the most industrialised states had been crumbling from within — much before the Left came to power. “The conventional understanding is that Bengal was doing great and then the communists came to power and destroyed the economy,” says Indraneel Dasgupta, an economist at the Indian Statistical Institute in Kolkata. “But if things were that good, why did the communists first come to power in the 60s?”

According to most commentators, the state was “comprehensively deindustrialised” by the Partition in 1947 followed by an allegedly stepchild-like treatment by the Congress government in the years to follow. “During the British rule, Calcutta thrived as a trading centre whose hinterlands reached right up to Burma and Singapore. With the Partition, overnight these trade routes were snapped,” Dasgupta says. “It was as though you physically tore up the network. The trade route stood devastated.”

Unlike Punjab, West Bengal was forced to grapple with a continuous flow of refugees from Bangladesh for decades, which would keep devastating the economy, he argues.

The freight equalisation policy, which subsidised the transportation of minerals to factories anywhere in the country, in 1952 further crippled Bengal’s economy, whose jute, steel, coal, tea industries had been spearheading national, not just state growth.

“The stated reason was obviously to have more balanced geographical growth across the country, but what it did in actuality was to take away the competitive advantage that Bengal had vis-à-vis the western states like Maharashtra,” Dasgupta adds.

The decades-old industrialisation had created a robust culture of labour unions. Coupled with the refugees who kept crossing over from Bangladesh, they formed a ready mass base for the Left parties.

As argued by academics Subho Basu and Auritro Majumder in an essay titled ‘The Rise and Fall of the Left in West Bengal’, the Left created a mass base both in urban and rural areas, which included small-time agrarian tenants struggling for land reforms, refugees demanding the recognition of squatter colonies in urban areas, white-collar working classes demanding better wages as well as the industrial working classes.

Meanwhile, a powerful cultural movement spearheaded by Left-leaning, party-affiliated intelligentsia — led by the Indian People’s Theatre Association —“helped the communists capture the imagination of the socially powerful and culturally hegemonic middle classes of West Bengal” through poetry, theatre, songs and films.

Several in the state believe that it was a romanticisation of class struggle that would provide the intellectual and cultural fodder for the communists for generations.

The Left years

In West Bengal, the Left parties first came to power in a coalition government of the United Front in 1967, and in 1969-70. The CPI(M)-led Left Front then formed the government in 1977, which would be in power for 34 years.

Within a year of coming to power, the Left Front enacted one of the most successful land reforms in India — Operation Barga (deriving its name from ‘bargadars’, or sharecroppers) — in 1978 that led to the fraction of registered sharecroppers rising from 23 to 65 percent from 1977 to 1990, and a 36 percent increase in agricultural production.

Moreover, as argued by independent researcher Partha Sarathi Banerjee, in ‘Party, Power and Political Violence in West Bengal’, it would further consolidate the Left Front’s base among the landless and the poor who belonged principally to the scheduled castes, scheduled tribes and the minorities, who together constitute over 67 percent of the state’s total population,

“Their reign for the initial years was a major success,” argues businessman Shishir Bajoria, who was with the CPI(M) for several decades before he joined the BJP in 2014. “The land redistribution that they implemented benefitted millions of landless workers. It broke the backbone of upper castes, and actually created a largely equitable society in terms of economic distribution.”

But, the land reforms also made the CPI(M) extraordinarily powerful. “You could now get a certificate of being or not being a sharecropper from the party workers,” BJP leader Swapan Dasgupta says. “So, in this roundabout way, they became the owners of the land — the nerve centre of village society.”

The Left’s insistence on class as being the only legitimate indicator of social identity as opposed to caste or religion, coupled with its land reforms, which broke the economic and social stranglehold of the rentier aristocracy and rich peasants, created a social vacuum in Bengali society, says Indraneel Dasgupta.

“There were no caste panchayats or the regular rich folks in the village who would resolve local disputes. Under Congress rule until 1977, this role was performed by zamindars, but after the complete abolition of zamindari, there was a social vacuum.”

Slowly, the Left Front created a ‘system’ in which admissions to schools and colleges, government hospitals, raising funds during natural disasters, and even arbitration of divorce settlements and extramarital affairs was done by party workers.

As argued by Banerjee that under the Left system, political affiliation became so important that even marriage between families with opposing political loyalties became rare.

“Party loyalty seems to have become the most important identity, crucial for one’s survival in rural Bengal, where houses can be burnt and people evicted only because they have chosen to vote for a party of their choice,” he writes.

The Panchayati Raj Institutions, through which government schemes were delivered, had a huge role to play in the creation and perpetuation of the party society. Soon enough, the panchayat became the unit through which the Left Front exercised complete control on society. Panchayat funds routinely came to be used to secure political support, argues Swapan Dasgupta

Being a resource-scarce society, control of resources and political power became inseparable. The Left Front ensured its political power through a tight control over resources through panchayats, and resources would often be delivered to those aligned with the CPI(M).

“The Left’s cadres and support base consisted of large SC, ST and Muslim populations that were so poor that even Rs 1,000 of cash was huge for them,” says Abdul Matin, a professor of political science at Jadavpur University (JU). “Those who could control the distribution of this cash money naturally became very powerful.”

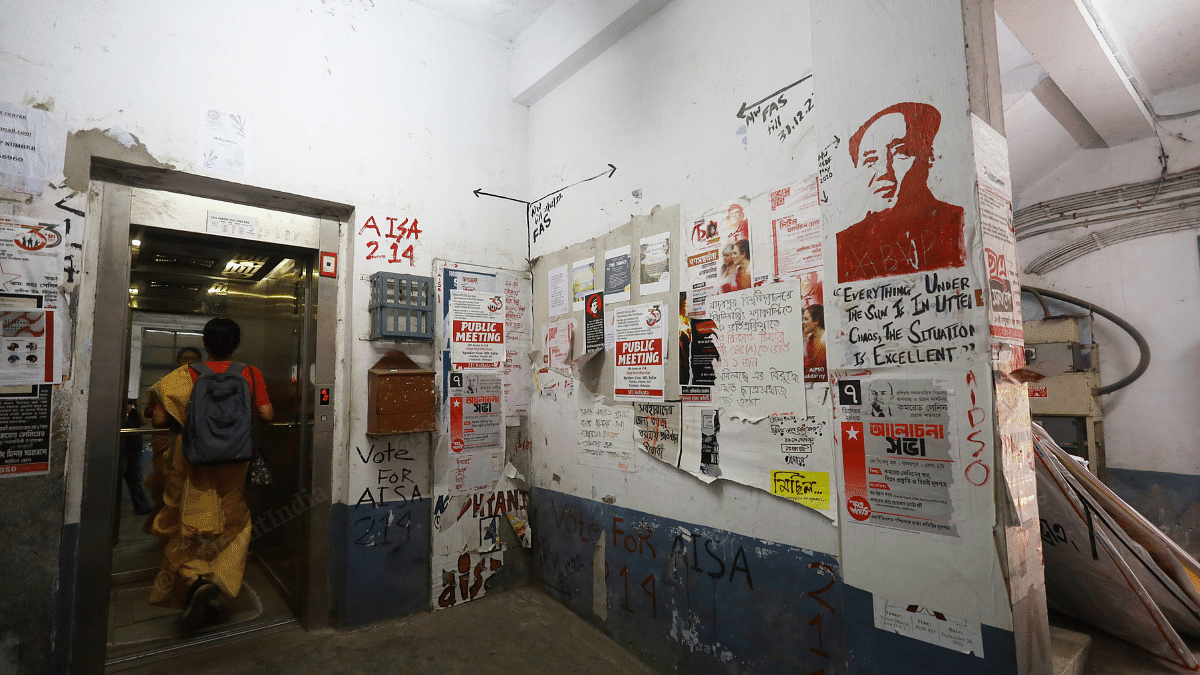

As a result, control over panchayats became non-negotiable, to ensure which, violence would be frequently deployed. As argued by Partha Banerjee, the proverbial statement of Mao Zedong that “political power comes out of the barrel of the gun” would reverberate literally in the hinterlands of Bengal.

The ideological & the non-ideological ‘Marxists’

The Left Front consolidated and perpetuated its rule through a carefully balanced combination of intellectual and armed power. “The poor SC, ST and Muslim populations, who were absolutely vulnerable economically, became the reserve armies of the Left, and could be deployed for political violence,” Matin says. “In a sense, these were ‘Marxists’ who had never read Marx.”

The local leadership at district and village levels consisted of the “middle class bourgeoisie” comprising school and college teachers, government clerks, etc, argues Dasgupta.

The leadership ran — according to Subhajit Naskar, also an assistant professor of political science at JU — the communist ‘shakha’-like organisations in villages, where texts of Lenin, Marx and Stalin would be widely translated in Bengali to influence people.

There was simultaneously a complete capture of the intellectual class in the cities at universities and colleges where the class struggle was glorified with giant posters and graffities of Marxist slogans, completely eclipsing its caste realities, he says.

“The so-called intellectual leaders were always the ‘Bhadralok’ (genteel), who actually disdained the people they claimed to represent. They would often disparagingly refer to them as ‘chotolok’ (lower class),” Naskar tells ThePrint.

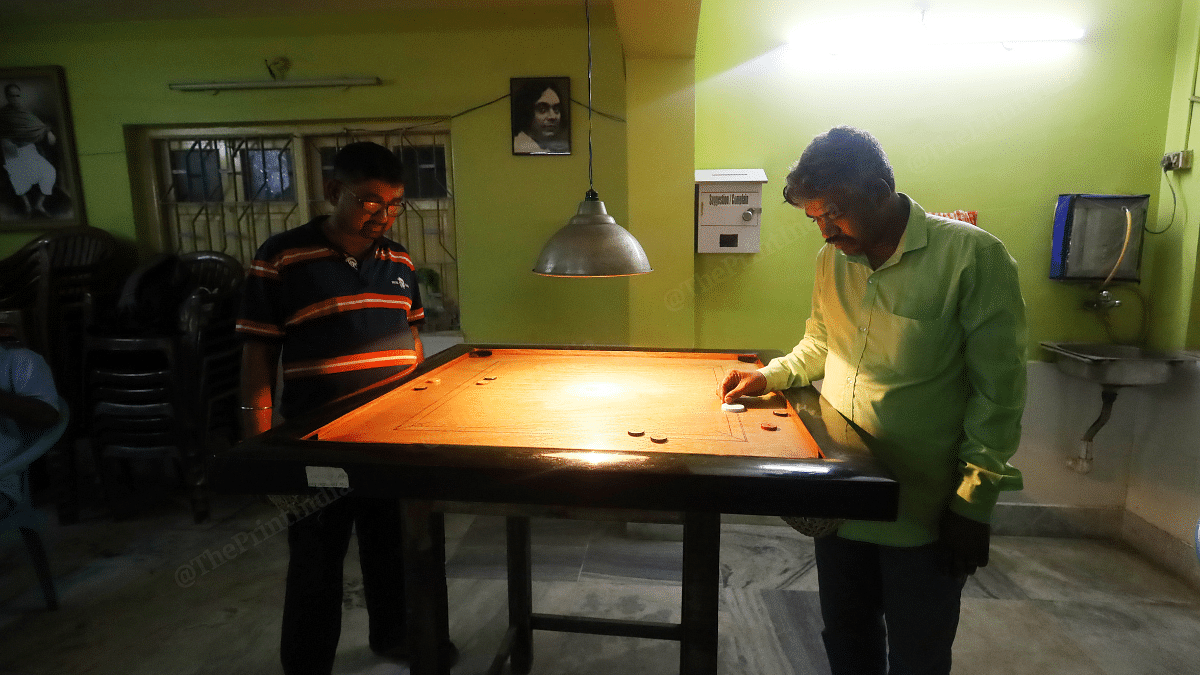

If the panchayats were used to expand the base in the villages, the local clubs in ‘paaras’ (localities) in cities became the nucleus for political mobilisation, and even intelligence gathering.

Families grow up giving ‘chaanda’ (donation) to these clubs for seemingly apolitical events like Saraswasti, Durga and Kali Pujo, say several Kolkata residents. Often, the collection is done by party workers.

Annual cultural and youth festivals, be it sports, debates, plays, were routinely organised to reinforce the idioms of Leftist politics, says Bajoria.

“The Left used to organise annual sports events, for instance, which paid huge political dividends because while the children played, the parents were made captive audience to be lectured on the greatness of Marx and class struggle,” says Bajoria. “It was a very smart ‘apolitical’ political strategy.”

Also Read: West Bengal politics has to be de-Brahminised. Dalit aspirations get dismissed daily

The Left’s existential undoing

What the Left Front did not realise was that its class politics would succumb to the law of diminishing, and ultimately negative returns, Bajoria asserts. “The land redistribution that was implemented so sincerely and successfully gradually started making landholdings so small that agriculture became unviable…Soon, it reached a point where everyone wanted to just sell land.”

But it was not just the Left Front’s own policies because of which the system they created began to unravel. By the mid-1990s, the effects of liberalisation began to echo throughout the country, and the government increasingly felt the need to spur industrial growth and urban development.

The first breach of its economic contract with working classes seemingly came in the form of ‘Operation Sunshine’ that took place in Kolkata in 1996. It is described by Basu and Majumder as “a state-sponsored effort to drive out street vendors and informal working populations from major avenues in an effort to reclaim ‘public space’.”

The breach slowly widened into a chasm in the next decade. A turning point came in 2006, months after the Left Front retained power for the seventh consecutive time.

Chief Minister Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee, who had promised industrialisation, announced that Tata would be given almost 1,000 acre to set up a plant to manufacture the Nano in Singur, and also an acquisition for a special economic zone in Nandigram would be made.

Protests broke out in Singur and Nandigram, but were ruthlessly crushed. The repercussions were far reaching: In 2011, the Left Front government was handed a crushing defeat so severe that even Buddhadev lost to his former chief secretary by 16,000-plus votes.

“The Left left back a sociologically wounded society,” says Naskar. “There was insurgency in parts of Bengal, there was industrial and educational backwardness, agricultural distress…Mamata solidified her base through her pro-poor, subaltern image, and promised to give a healing touch to a wounded society.”

Societal changes under two govts

While she inherited a “party society” from the Left Front, Mamata had neither the ideological cohesion and commitment, nor the organisational, almost corporatist, structure, through which the Left had penetrated and perpetuated its rule.

“Under the Left, even when there was corruption or violence, it was planned to the T by the party. The local committee, which was subordinate to the district committee, would never do something without its knowledge. Similarly, the district committee would not do something without the state-level committee’s knowledge,” says Bajoria. “Unki gundagardi mein bhi discipline tha (There was discipline even in hooliganism).”

BJP leader Swapan Dasgupta agrees. “The Left was ideologically motivated, and that brought a degree of organisation structure to how they governed the state — they had a very rigid system of control that could not be breached.”

There is, of course, a communist reason for this. Sourjya Bhowmick, author of ‘The Gangster State: The Rise and Fall of the CPI(M) in West Bengal’, tells ThePrint that the party was strictly committed to Lenin’s “democratic centralism”, in which the central control supersedes democracy.

Mamata, on the other hand, rose as a one-woman army, a street fighter with no organisational structure to back her up. Even as the Left cadres are believed to have shifted en masse to the TMC after she came to power, the organisational structure through which they had operated under the Left stood obliterated.

As argued by Dwaipayan Bhattacharya, a professor of political science at Jawaharlal Nehru University, in a piece for The Hindu, “Ms. Banerjee realised early on that although she had to work with party society, she could not run a government the CPI(M) way. In her party, she alone drew universal authority without any stable hierarchy of command.”

She would seek to substitute the Left’s organisational structure by emboldening chieftains who would provide muscle and money power during elections, but would demand complete autonomy to run their areas as their personal fiefdoms.

Thus sprang up Arabul Islam in Bhanghar, Anubrata Mondal in Birbhum, Sheikh Shajahan in Sandeshkhali on whom Mamata depends for sustaining her political power in the absence of a strong political organisation. Mostly from humble and vulnerable social and economic backgrounds, these strongmen have been armed for consolidating political control.

“Even the Left made use of petty criminals in some cases during elections and so on…But they were never given political power. They remained decisively subordinate to the party,” claims Badshah Moitra, TV actor and CPI(M) supporter. “In the TMC, these people are doing whatever they want with no ideological purpose and complete impunity.”

“Under the CPI(M), cases of personal corruption were far and few in between. Besides, their leaders coming from the educated middle classes were not very business-oriented,” says BJP’s Swapan Dasgupta. “Under the TMC, the leaders are business-minded, ambitious, neo-rich politicians…They were there in the Left too, but they were not controlling the party. They were only using their proximity to party to their limited advantage. Under the TMC, they are the party.”

A farmer in Birbhum district concedes that they either paid money or share a part of their produce in the Left Front’s years, but the scale was less. “I own less than an acre of land, and three years ago, it was captured by a TMC worker…Now, I work like a tenant on my land,” he says, adding there were “several others” like him.

Under the Left, there was more party control, less money politics. Now, there is less party control, more money power, often exerted through the businesses run by local strongmen in villages and “syndicates” in the cities.

“Under the Left, the strategy was ‘kom khele, beshi khabhi, baishi khabi, kom khele’ (If you eat less, you can eat longer, if you eat too much, you cannot eat for long enough)…That’s why they could last for 34 years, while the TMC system is already unravelling),” points out Bajoria.

TMC’s strongmen have important social roles which they perform, too. “They offer the same dispute resolution services which the Left leaders did before but at a higher cost,” Indraneel Dasgupta argues.

But as argued by economist Suman Nath in ‘Everyday Politics and Corruption in West Bengal’, they also ensure accelerated service delivery. In contrast to the Left Front, Nath writes, “TMC could deliver things to the people relatively quickly, often through a corrupt form of exchange. Yet, because of the speedy and assured delivery of services, a large section would approve this mechanism.”

Moreover, these strongmen are the main employers and patronage-givers in the informal economy in a state where industrial decline is steady.

‘Syndicate Raj’

This “system” — which Prof. Bhattacharya refers to “franchisee politics”, i.e. under which, local leaders run their “franchisees” under Mamata’s name in lieu of their “services” — primarily functions on the basis of the “syndicate system” and “cut money”.

A relic of the Left Front rule, the syndicates came about with the purpose of providing local unemployed youths some earnings through supply of construction material to builders and real-estate developers. But over the years, they have transmogrified into organised extortion rackets.

In March, Prime Minister Narendra Modi raked up TMC’s ‘tolabazi’ at a public meeting in Nadia’s Krishnanagar.

“TMC’s ‘tolabazi’ politics decides everything. Their leaders want a cut in everything. In Bengal, about 25 lakh fake job cards were created in MGNREGA. Even those who are yet to be born have job cards in their name. TMC’s ‘tolabaz’ leaders looted people’s money,” he said.

This syndicate system and local ‘dadagiri’ (intimidation), which people associate with Bengal, got crystallised under the Marxist regime, says TMC Rajya Sabha MP Jawhar Sircar. “Suppose someone is building a house, the unemployed youth would come and say,’ we will not allow your trucks to come in, if you do not get stone chips or cement from us…’ I know because I was serving at the time,” the former IAS officer says.

The issue points to a larger problem of the systematic deindustrialisation, which cannot be attributed to any one party, he adds.

The above-mentioned Kolkata-based businessman, who said that the culture of cut money has existed for generations, too concedes that the problem persists irrespective of the party in power. “A friend of mine who recently opened a factory in Howrah declined to comply with party authorities. The day he denied shelling out cut money to the party workers, tyres were punctured of tempos that supply raw materials in wee hours. It happened two years ago.”

With the BJP trying to consolidate its position, a Hindu-Muslim slant is being infused in the decades-old institutionalised corruption and criminalisation of Bengal’s political economy. The likes of Sheikh Shajahan, alleged to have perpetrated horrific crimes on the largely Hindu SC population, fit well into this narrative.

But, Matin argues such narratives are merely facades to keep the real causes far from the discerning eyes. “What appears to be appeasement is actually weaponization of petty Muslim criminals, for which, the TMC is to be blamed…But what a Hindu-Muslim narrative hides is the economic and political rot within, which enables the likes of Sheikh Shajahan,” the JU professor says.

With inputs from Manisha Mondal

(Edited by Tony Rai)

Also Read: 10 dirtiest cities are in ‘waste Bengal’. Kolkata to Kalyani, people clip noses, accept it

And the same way, most goons in TMC are already under the bjp. Most saffron goons are trying to threaten the village structures, after having shifted from tmc. Sanya avoids that