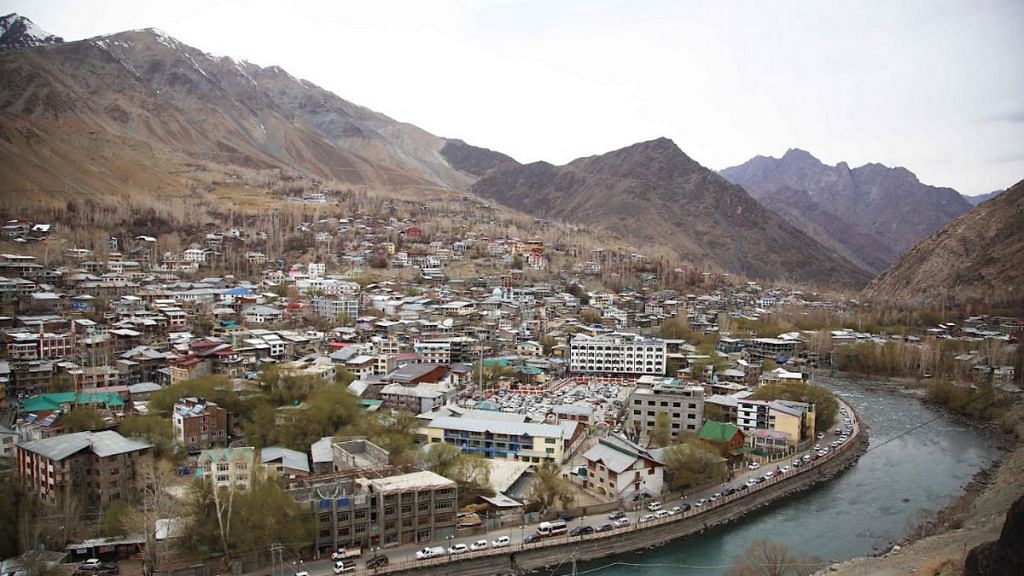

Leh/Kargil: After a long history of mutual mistrust, Ladakh’s Buddhist-majority Leh and Shia Muslim-majority Kargil districts have joined forces for the first time, united in their anger against the central government as they protest for statehood and constitutional safeguards under the Sixth Schedule.

This newfound unity follows years of communal clashes and resentment, with both districts accusing the erstwhile Jammu & Kashmir state government of discrimination in favour of the other. The abrogation of Article 370, which subsequently led to Ladakh becoming a Union territory, further deepened the divide. While Leh residents celebrated the move, Kargil vehemently opposed it.

“It is true that Leh and Kargil have had differences,” said Sajjad Hussain, leader of Kargil Democratic Alliance, speaking to ThePrint. “The major concern was that of (political) identity, since Ladakh has only one Lok Sabha seat. Sometimes Kargil would complain about being neglected, sometimes Leh would complain about more funds coming to Kargil. Each district wanted their own person to be on the Lok Sabha seat.”

Previous flashpoints between the districts include a 1989 communal clash that began with a scuffle between a Buddhist youth and four Muslims, leading to a three-year boycott of Kargil residents by Leh. Widespread violence also erupted in 2006 following the alleged desecration of the Quran at a mosque

But such historical grudges paled in comparison to the current struggle for “Ladakh’s autonomy and existence”, Hussain said. “This has compelled us to join hands and come on the same page.”

Echoing this, Dr Mohammad Jaffar Akhoon, chief executive councillor (CEC) of the Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council (LAHDC) in Kargil said that the past issues between the districts are extremely petty and small in front of the threat that Ladakh is facing today.

Ladakh has been witnessing protests due to multiple interconnected grievances, including the BJP not fulfilling its 2019 manifesto promise to provide the UT more autonomy under the Sixth Schedule of the Constitution. The residents of Ladakh, where tribals make up about 90 percent of the population, are now taking a stand against “democratic marginalisation”, militarisation of ecologically sensitive areas, and concerns about unchecked development projects. They are also demanding job reservations and statehood.

However, officials in the UT administration told ThePrint that granting Ladakh statehood or even making it a UT with a legislative assembly could ultimately worsen tensions between the two districts. An official also pointed to Ladakh having the “highest per capita number of elected representatives” in India.

Also Read: Why Ladakh is angry with central govt — power dynamics, joblessness & ecological concern

Statehood may lead to ‘more fights’

While Leh and Kargil continue their joint fight for “autonomy” and “survival”, there are apprehensions within the government that granting these demands might lead to further destabilisation and conflict, given the fundamental differences in the districts’ goals.

“Both districts have their own socio-economic and political goals. That is the reason they have had differences for years,” said an official in the UT administration.

He pointed out that granting statehood or instituting a legislative assembly would necessitate a delimitation exercise, which could open new faultlines. The official predicted that if delimitation took place, Kargil would ask for constituencies to be carved out on the basis of population since it has a greater number of people, while Leh would ask for it based on territory since it covers a greater area.

“There is not going to be any consensus between the two districts and it will lead to more protests and fights, and blow into a controversy. It is good that both districts have finally resolved their issues, but the government fears that if statehood or UT with legislative assembly is granted, it may become a flashpoint,” the officer said.

There is already a demand in Ladakh for a separate MP seat for both Leh and Kargil, he added.

Also Read: Student leader, lawyer & a ‘sharp’ politician’ — who is Tashi Gyalson, BJP’s candidate for Ladakh

A democratic setup already in place?

Ladakh’s demand for autonomy is unreasonable because it has the highest number of elected representatives relative to population, argued a second UT administration official.

“The total elected representatives in Ladakh are the highest per capita. There are panchayats, hill councils, and municipalities—and elections are held for all,” he said. “How can the people say that there is no autonomy or power to elect their representatives? Is this not political representation?”

Ladakh has a distinct political setup, comprising two autonomous hill development councils (LAHDCs) that manage local administration and are elected every five years. While the Leh LADC is led by the BJP, the Kargil LADC is led by the Congress and National Conference. Key officials, including the district commissioner, report to these councils.

Each LAHDC has 30 councillors, of which 26 are elected and four nominated. The councils are vested with various powers listed in the Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Councils Act, 1997, including allotting state land (called Khalsa) to private entities or government bodies and making key decisions on forests, education, and healthcare. Although the councils do not have legislative powers, they can make by-laws, rules, and regulations on the subjects mentioned in the list. The LAHDCs operate similarly to a state government, where the chief executive councillor acts like the chief minister, with four executive councillors forming the equivalent of a cabinet.

The second officer also added that Ladakh has a very small population of 2.7 lakh people and a separate state is not a “feasible idea”,

“If they are given a legislature, how many power centres will there be? There will be the hill councils and top of that there will be the legislatures, won’t that erode the powers of the councils? If legislative assembly is granted then there will be another layer of administration over the hill councils. Won’t this make it more complex?” the officer asked. “These are practical issues one needs to take into account.”

However, environmentalist Sonam Wangchuk, the main face of the protests, dismissed the contention that Ladakh already has an adequate democratic setup. According to him, the J&K Lieutenant Governor pulls all the strings.

“This is such a flawed argument. If you look at Ladakh’s budget, it is Rs 6,000 crore, but only 10 percent— crumbs—are thrown to the administration,” he said.

According to him, the J&K Lieutenant Governor pulls all the strings. “The powers of these councils have all been diluted, they cannot function without the approval of the LG officer,” he said. “And then they say there is democracy. Is it really a democracy?”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)