New Delhi: In the Maoist-affected tribal heartland, two Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) personnel died of gunshot wounds just two days apart in August. Both their injuries were self-inflicted, using their service weapons. CRPF officials attributed both suicides to “family issues”, but these deaths are a grim reflection of a bigger problem.

The suicide rate in the central armed police forces (CAPFs), which include the CRPF, Border Security Force (BSF), Indo-Tibetan Border Police (ITBP), National Security Guard (NSG), and Sashastra Seema Bal (SSB), Assam Rifles, and Central Industrial Security Force (CISF) is inordinately high when compared to that of men in a similar demographic.

The suicide rate among educated males (graduates or above) was 8.9, according to a Lancet analysis of the 2021 National Crime Records Bureau statistics. However, the suicide rate is 13 for CAPF personnel, based on the number of troops working at the start of 2023 and the total suicides in 2022. The suicide rate is the number of suicides per 100,000 people in a given population.

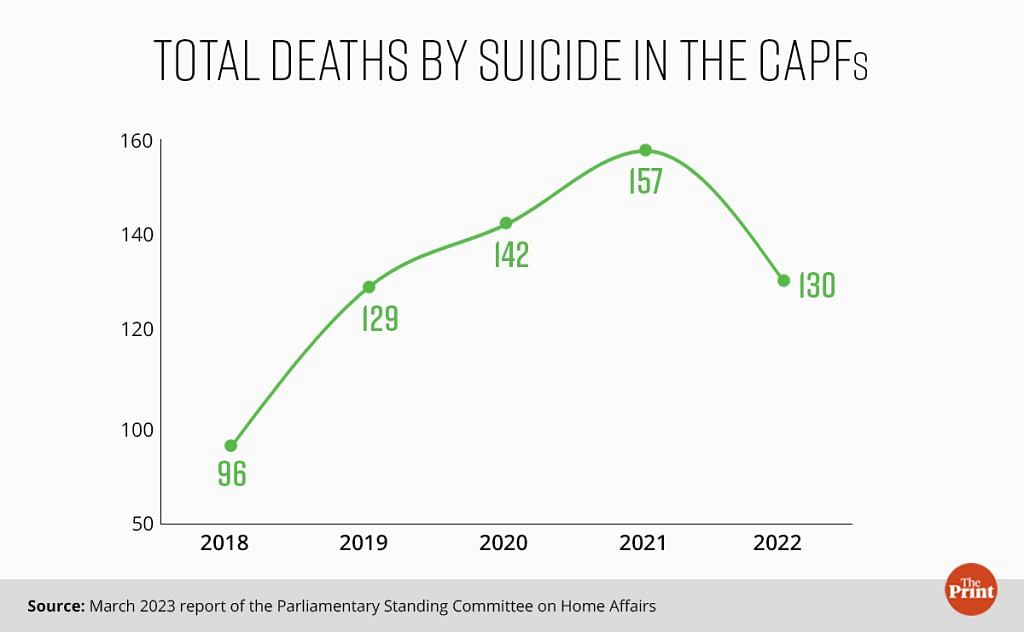

According to data from the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA), 654 CAPF personnel died by suicide between 2018 and 2022. This means that, on average, one member of the CAPF died by suicide every three days over the past five years.

The highest number of suicides among the CAPFs in this period was recorded for the CRPF at 230, followed by the BSF at 174 and the Central Industrial Security Force (CISF) at 89.

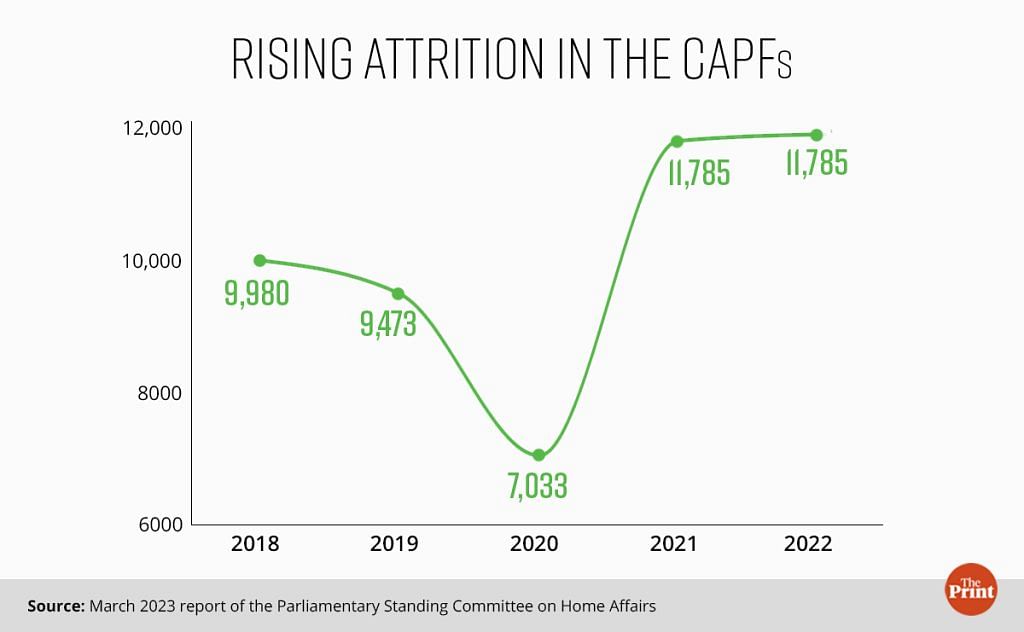

Another problem is attrition. In the same five-year period, 50,155 CAPF personnel quit their jobs. On this front, the total numbers were highest for the BSF at 23,553, followed by the CRPF at 13,640 and the CISF at 5,876.

Senior officials from various CAPFs, including the CRPF, told ThePrint about the persistent stressors these personnel face, including extended deployments in risky areas, harsh conditions, family separation, and inadequate leaves.

When coupled with personal issues, stigma around mental health, and access to firearms, this becomes a volatile mix.

A CRPF officer pointed out that, unlike the Army, personnel of the paramilitary forces often do not get time to recuperate between demanding assignments.

“The situation is quite unlike the Army, where they get peace postings after serving in challenging postings such as at the Line of Control (LoC),” the officer said.

The alarming suicide and attrition figures have caught the attention of the highest levels of government. A report from the standing committee on Home Affairs, presented to the Rajya Sabha on 15 March this year, acknowledged the “inhospitable” working conditions for many CAPF personnel.

“Urgent measures may be taken to improve the working conditions significantly to motivate the personnel to stay in the force,” the report, of which ThePrint has a copy, said.

Also Read: Why Assam Rifles’ vilification is a calculated, conniving move for revenge

‘Perpetual stress’ in CRPF

On 18 August, Safi Akhtar, an inspector in the CRPF’s elite Commando Battalion for Resolute Action (CoBRA), ended his own life in Bijapur, Chhattisgarh. He used his service rifle. The very next day, Jagdish Meena, stationed at the Kekrang CRPF camp in Jharkhand’s Maoist-affected Lohardaga district, followed suit.

These were not isolated incidents. This year alone, 34 CRPF personnel lost their lives to suicide. Ten of them died between 12 August and 4 September, according to CRPF sources.

Home Ministry data shows that there were 36 suicides in the CRPF in 2018, rising to 40 in 2019, 54 in 2020, and 57 in 2021. The numbers dipped to 43 in 2022.

The main mission of the CRPF, India’s largest paramilitary force, is to help maintain internal security, including combating insurgencies in Naxal areas. They are also deployed in large numbers in Jammu and Kashmir to help maintain law and order.

In addition, the CRPF plays a key role in ensuring the conduct of free and fair elections at both the national and state levels. However, their responsibilities go well beyond these core duties.

The CRPF officer quoted earlier told ThePrint that many state police forces lack the resources, training, and manpower to handle law enforcement crises effectively, resulting in the CRPF being called in to assist. The officer added that CRPF personnel are also deployed to maintain order at routine events like fairs and festivals, including Ganesh Chaturthi in Maharashtra and Rath Yatra in Odisha.

This means that personnel rarely get a break and are in a state of “perpetual stress”, said the officer.

Another senior CRPF officer echoed this. He said that the nature of the duty was such that there was no cooling-off time for the troops. He added that prolonged phases of stress have become a “professional hazard” for CRPF personnel, especially since they are often isolated from their families.

Limited promotions, prestige issues

Suicide is not just a serious problem in the CRPF. Between 2018 and 2022, there were 174 suicides in the BSF, 89 in the CISF, 64 in the SSB, 54 in the ITBP, and 43 in the Assam Rifles. The NSG fared better, recording three suicides in this five-year period.

A senior BSF officer, speaking on condition of anonymity, said that not only are working conditions tough, there is limited scope for promotions, which affects morale.

“Personnel have had to serve in the same post for as long as 10 years in some cases,” he said.

The officer explained that promotions are based on vacancies at different levels. The number of posts at the higher ranks is limited based on the sanctioned strength, and as a result, there is a mismatch between the number of people eligible for promotion and the availability of vacancies.

Another BSF officer told ThePrint that ranks above the Deputy Inspector Generals (DIGs) are reserved for officers of the Indian Police Service (IPS) and the Indian Army. This means that BSF personnel who have spent their younger years around remote border areas feel dejected at “hitting the roof” in terms of promotion in the force.

A third BSF officer explained that BSF troops serve equally rigorous postings across the border areas as the Army, but their families do not receive the same level of services and security.

For example, he said, Army personnel do not have to worry about the health and treatment of their immediate family members because there are Army hospitals in every major city. Additionally, the range of products that the canteen stores of the Army provides to families of soldiers who are away on duty is much wider than what is available to those of BSF personnel.

This officer also told ThePrint that the families of personnel often get into disputes, especially related to land ownership, due to their long absence from home.

He claimed that when the personnel try to resolve these disputes at the local level, police officers often tell them that they only recognise the Army, Navy, and Air Force as “real” forces. This leads to further demotivation among the troops, the officer said.

The pension scheme is another big sore spot. The second BSF officer said that troops working in CAPFs are eligible for pensions under the New Pension Scheme (NPS), which beneficiaries have complained of as having very low monthly disbursements. Armed forces personnel, on the other hand, receive pensions under the Old Pension Scheme (OPS).

Notably, on July 7, the Supreme Court stayed a Delhi High Court order that approved the old pension scheme for all CAPFs as they are “armed forces of the Union”.

In the case of the CISF, responsible for safeguarding strategic infrastructure, the challenges are slightly different.

According to CISF spokesperson Shrikant Kishore, personal, financial, and family issues are the primary triggers for suicides among CISF troops.

Kishore said internal studies conducted by the force revealed that some personnel get lured into gambling and get-rich-quick schemes and then reach the point of despair when the financial losses rack up. Family-related stress, he added, was a major risk factor for suicides among CISF personnel too.

Alerts at the highest level

The issue of suicides among CAPF personnel has been a long-standing concern for policymakers.

In December 2021, the MHA, responsible for overseeing CAPFs, constituted a task force to look into the matter. The task force, comprising high-level officers from all the CAPFs, was given a mandate to identify the risk and protective factors at the individual level, study prevention strategies, and conduct research in collaboration with domain experts.

First headed by the then director general of CRPF Kuldiep Singh and later by V S K Kaumudi, former special secretary for internal security in the MHA, the task force submitted its draft proposal earlier this year.

This document, a copy of which ThePrint has seen, outlined three broad risk areas that contribute to suicide in the CAPFs — working conditions, service conditions, and personal/individual issues.

On working conditions, the task force highlighted the extended deployments in high-risk areas, particularly for CRPF, ITBP, BSF, SSB, and Assam Rifles personnel. These troops, the report said, grappled with extended separations from their families as well as fatigue and depression due to long duty hours in adverse climatic conditions.

Among the service conditions, the task force highlighted leave-related problems in the ITBP, CRPF, BSF, SSB, and Assam Rifles. Additionally, CRPF, CISF, and Assam Rifles personnel faced insufficient time for rest and recreation, the report said.

Lack of job satisfaction, especially when compared to counterparts in other sectors, also played a role in suicides among CISF, CRPF, and Assam Rifles personnel, it added.

Furthermore, frequent transfers of company commanders in the ITBP and SSB disrupted communications with troops, serving as another challenge for these forces, the report pointed out.

On the personal front, mental health disorders emerged as significant factors affecting CRPF, BSF, SSB, and Assam Rifles personnel. Domestic issues and land-related disputes were notable stressors for personnel in the BSF, CRPF, SSB, and Assam Rifles, the report said.

Notably, even before the formation of this task force, concerns regarding suicides had surfaced at the parliamentary committee level.

In 2021, the parliamentary standing committee on Home Affairs observed that leaves at proper intervals are a “necessity” for CAPF personnel, given the challenging nature of their duty in harsh climatic conditions.

“CAPFs function under much duress, given the nature of their duty which requires their postings in harsh climatic conditions. So, to ease their mental state and reduce stress, leaves at appropriate intervals are a necessity, so that they can spend time with their families,” the report said.

The committee also noted that the MHA was deliberating over the possibility of increasing leaves for CAPF personnel, recommending that this should be “finalised at the earliest” in order to “boost the morale of the CAPFs”.

Helplines, counselling, ‘buddy system’

The different CAPF forces are in the process of implementing strategies to help take the pressure off personnel.

“The leadership is alive to the situation and we are taking steps to relieve the personnel of stress,” said the first senior CRPF officer.

However, he acknowledged that lending support for personal and family issues was more “manageable” than changing working conditions.

“The mandate of the CRPF doesn’t allow a cooling off period after hard duty for troops, unlike the Army,” he said.

Nevertheless, he added, the CRPF administration has instituted a “buddy system” in which two personnel are paired together to better understand each other’s habits and routines.

This initiative serves as an early warning system, alerting company commanders and assistant commandant-level officers, who are typically stationed with battalions, to the mental well-being of their respective “buddies”.

Efforts are also on to improve the mechanisms for requisitioning leave so that the process becomes “more easy and prompt”, said the second CRPF officer.

“The CRPF has launched an e-leave platform on the SAMBHAV app which allows personnel to apply for leave instantly from a click on their mobile phone. The leave sanctioning authority can then sanction leave on the e-leave portal,” he added.

This officer also said that a “clear message” has been sent to all commanders and assistant commandants to engage on a one-on-one basis with their subordinates in a “formal setting”. These interactions include inquiries about marital status, the health of their children and parents, and overall well-being at home.

“Cases of depression and mental illness are kept under watch around the clock and maximum efforts are made to allow and encourage family members to stay with such personnel,” the officer said.

Mental health counsellors have also been roped in by the CRPF to improve the “emotional well-being” of troops. Efforts are now on to extend these services even in remote areas, the officer said.

“After careful consideration, it has come to light that most of the suicide cases in the force are attributable to family disputes, marital discord, illnesses, and other personal reasons, illness, apart from a few instances where there were professional factors,” the second CRPF officer said.

“Serious efforts have been made to ensure a conducive work environment and grievance redressal to minimize suicides in the force,” he added.

Officials in other CAPF forces also echoed similar sentiments, identifying poor mental health as a significant factor behind the suicides of personnel.

BSF officials told ThePrint that a dedicated helpline has been set up for troops in need of assistance, in line with recommendations from the MHA task force.

Since the task force had highlighted disputes over land as a major stressor, BSF officials said the headquarters were trying to engage on the behalf of personnel with local authorities in such matters.

In June, the BSF partnered with the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) in New Delhi, allocating a budget of about Rs 20 lakh this year for counselling services for personnel.

“This initiative is being received well by troops on the ground,” the second BSF officer told ThePrint.

Much like the BSF, the CISF too has set up a helpline for personnel, among other measures.

“The CISF has set up a dedicated helpline number and started a special certificate course known as the Mental Health Championship Program for supervisors of its units,” CISF spokesperson Shrikant Kishore said.

“Under this policy, supervisors go through a course where they learn about the signs of mental health problems. It can help them detect any such issue among their subordinates,” he added.

Kishore said that the CISF has enlisted the expertise of counsellors to improve the mental well-being of troops. The service is currently available in only 27 units, but there are plans to eventually extend it to all 355 units of the force.

Massive attrition

The various CAPFs, which are collectively entrusted with guarding international borders with China and Pakistan, maintaining internal security through anti-insurgency operations, and supporting state police forces to ensure law and order, have experienced an average of 27 personnel leaving their service every day over the past five years.

The BSF has borne the brunt of this issue, with 23,553 personnel departing between 2018 and 2022. A major spike in attrition occurred in 2021 and 2022, with 5,713 and 5,749 personnel quitting, compared to just 3,521 in 2020. The years 2018 and 2019 also witnessed significant attrition at 4,283 and 4,287 respectively.

In the case of the CRPF, where 13,640 personnel quit in the last five years, there has been a major spike too. In 2020, only 1,410 personnel left the ranks, but this figure more than doubled in the subsequent two years, reaching 3,633 and 3,101, respectively.

Following the BSF and CRPF, the CISF and (CISF) and ITBP faced significant losses over the past five years, with attrition figures of 5,876 and 2,915, respectively.

Calling the situation “problematic”, the first BSF officer said that various factors could contribute to attrition, including personnel seeking better financial prospects. He added that not much could be done about it.

“There is a competitive environment,” he told ThePrint. “One cannot stop others from moving on if they believe they have a far better life outside of the force.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)