New Delhi: As India sees a renewed surge in Covid cases accompanying concerns around the spread of Omicron variant infections, what has also raised eyebrows in recent months is the number of Covid deaths being reported in the country.

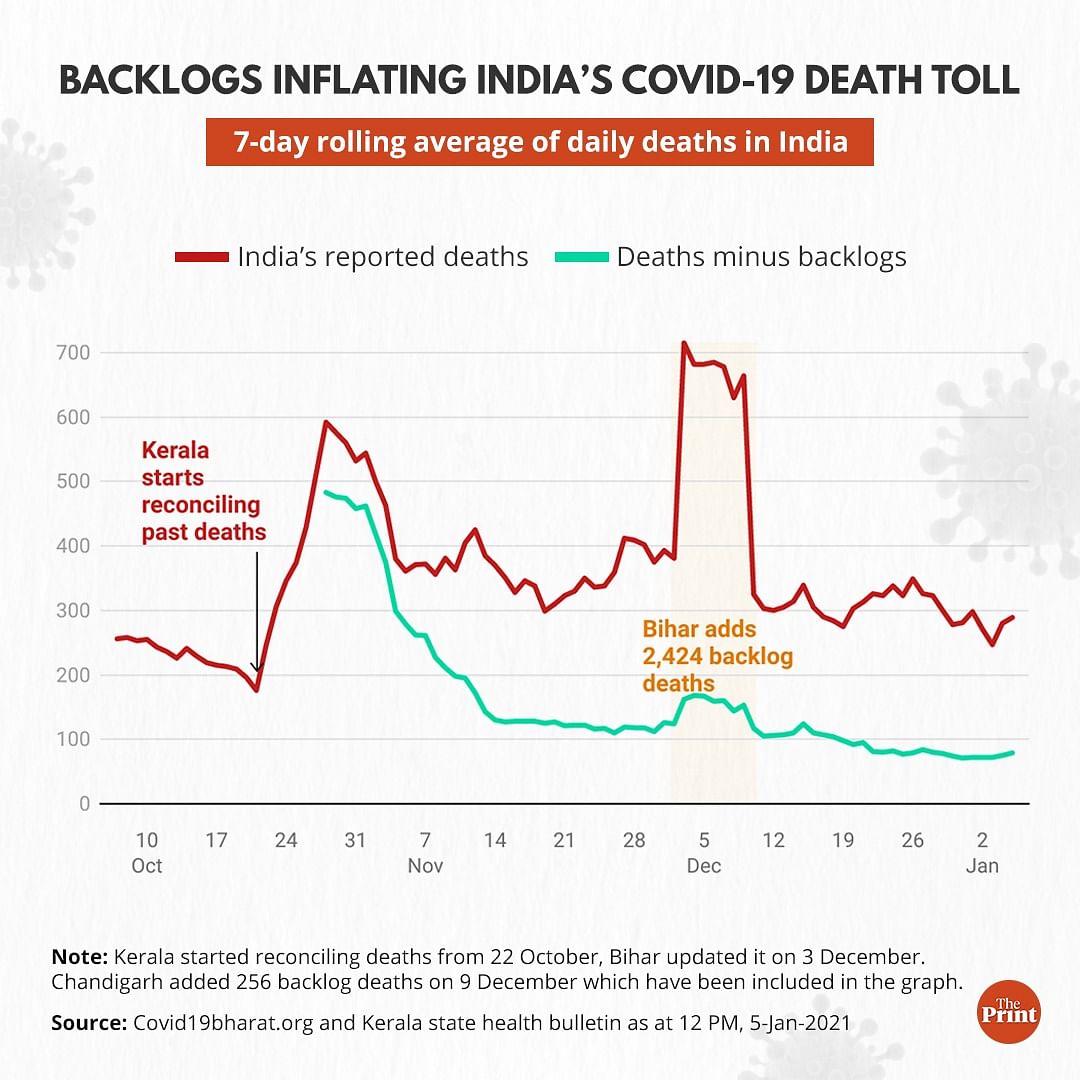

In the first five days in January 2022 alone, the country reported 1,391 Covid deaths, according to covid19bharat.org, a crowdsourced platform compiling the numbers put out by state health bulletins. The number of Covid deaths reported in the country between 22 October 2021, and 5 January 2022, stands at 29,836. Considering that India’s Covid cases had shown a downward trend between August and October last year (down from 40,000 per day to 15,000 per day on average, according to Covid19bharat.org), the death tally of 29,836 is considerably high.

What is important to understand here, however, is that not all these are new deaths, but casualty backlogs that are being reported now, increasing the total death tally.

Since 22 October, the states of Kerala and Bihar and the union territory of Chandigarh have reported more than 17,000 backlog deaths. Which means the number of fresh deaths reported in the country between 22 October and 5 January is 12,823 or about 2.3 times less.

Of the 17,000 backlog deaths, more than 14,500 have been reported from Kerala alone. While Kerala has been updating the numbers gradually, Bihar and Chandigarh had reported a one-time update. On 3 December, Bihar added 2,424 backlog deaths to the state’s casualty lists, while Chandigarh added 256 backlog deaths to its numbers on 9 December.

The focus on Kerala

The two states and the UT of Chandigarh are not the only ones to have updated their casualty figures in recent months. Between May and July last year, Maharashtra had added 23,000 backlog deaths to its Covid casualty lists — a bigger number than that reported by Kerala so far. Madhya Pradesh too had added 1,478 deaths as backlogs in July last year. Bihar’s update of its death toll in December was the second such by the state last year. In June, the state had added 3,951 backlog deaths to its total casualty.

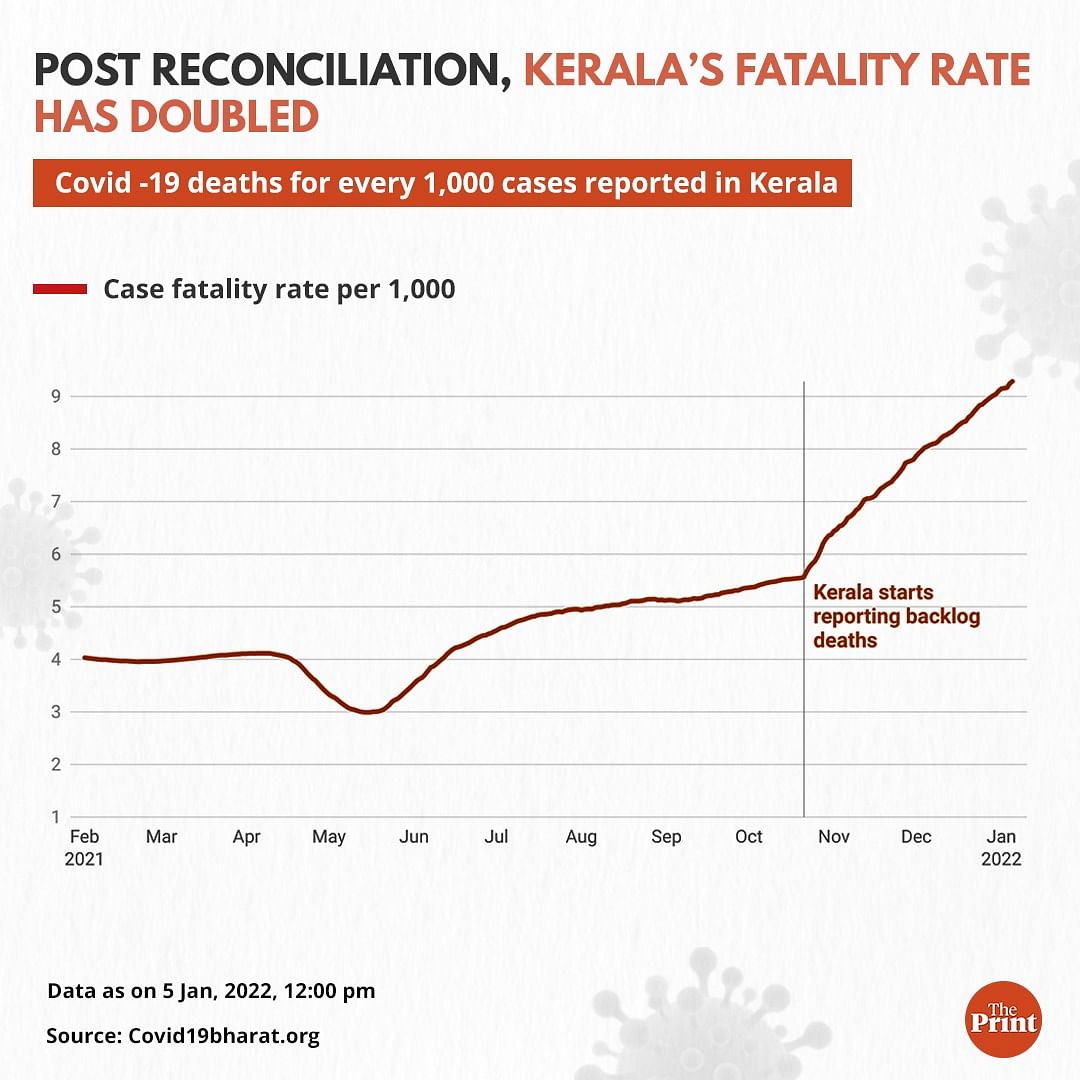

However, the reporting of backlogs in Kerala has attracted more attention since the state was earlier said to have had the lowest Covid fatality rates in the country.

“Kerala’s mortality from Covid-19 has more than doubled in the 2nd wave compared to the first due to the addition of backlog deaths. The merit of its claims of being a state with the lowest mortality from Covid-19 has significantly diminished,” said Rijo M. John, health economist and adjunct professor at Kerala’s Rajagiri College of Social Sciences.

John’s statement stems from the fact that before the reconciliation happened, Kerala had a total of 27,202 reported deaths for 48,88,523 cases — which means that the state was then reporting 5-6 deaths for every 1,000 cases. However, as on 6 January, the state’s total death toll has reached 48,895 against 52,63,415 reported cases, which means 9 deaths for every 1,000 cases.

The reporting of backlogs has pushed up the Covid death toll reported in the past two months to at least two-three times higher than what the actual new death figures are.

But Kerala’s updated death figures are not a result of the state performing poorly or reporting abnormally high casualties, but because it has been updating its death backlog more vigorously and thoroughly than other states.

“The overall Covid-19 mortality of 0.92 per cent in Kerala based on reported deaths, however, continues to be lower than that of the national average at 1.38 per cent. It should also be noted there are significant amounts of excess deaths in many other states as shown by several studies although not officially acknowledged,” said John.

Also read: Raipur worst, Delhi bad, Mumbai best in mask-wearing amid Covid surge, finds think-tank study

Why backlogs are being counted

In June last year, the Supreme Court of India directed the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) to frame guidelines for providing compensation to the families of those who died of Covid-19. In the same order, it had also asked for simplifying reporting Covid-19 deaths.

It was this order which prompted Kerala and many other states to reconcile their death figures to ensure payment of compensation to victims’ families.

On 11 September, the NDMA sent its guidelines to the chief secretaries/administrators of all states and UTs, under which families of Covid deceased could avail ex gratia compensation of up to Rs 50,000.

Based on the ICMR guidelines, it also notified that anyone who had tested positive for the disease and died within a month of that would be considered as having died of Covid.

Since October 2021, Kerala has been reporting both fresh Covid deaths and those from the past which had not been included before, as instructed by ICMR.

In October last year, the state’s Health Minister Veena George had announced that all the deaths that were not reported due to insufficient documentation before 16 June (when the Kerala’s system of reporting deaths went online) would be reconciled. Though it was announced that more than 7,000 such deaths would be likely reported, the number that has come in since has already crossed this figure. The state in its daily health bulletins also mentions 3,779 deaths as “pending appeals”, which means the backlog figure is likely to go up further.

Not all states, however, have been equally methodical in casualty counting and payment of compensation.

In December last year, the Supreme Court had rapped several state governments for either not initiating the payments or paying very few of those who applied.

The number of eligible applications for ex gratia compensation is also an indication of the extent of undercounting of Covid-19 deaths by the states.

For instance, the Gujarat government sanctioned a list of 16,175 people as being eligible for the compensation, while it had reported only 10,099 deaths. The state’s Health Minister Rushikesh Patel had been quoted as saying, however, that the government “had no plans to update the Covid death toll”.

Hence, there are 5,176 deaths that are being considered for ex gratia payments, but unlike in Kerala, these have not been reported as Covid deaths in Gujarat’s health bulletins.

If all other states start reporting their backlog deaths, then Kerala’s sudden jump in Covid-influenced mortality may not seem abnormal, said John.

Epidemiologically deceptive

To understand the pandemic and address it on time, policy makers need vital information that comes from real-time reporting, and hence, delaying data could be misleading, experts say.

“One place where the late addition of deaths really matters is in our ability to assign an infection fatality ratio (IFR) to Covid-19, a measure of how many deaths result from a certain number of infections,” said Gautam Menon, professor of physics and biology at Sonipat’s Ashoka University.

“Knowing the IFR in each age bracket, say 10-20, 50-60 etc adds further value, because we know that the risk of death from Covid-19 rises very steeply with increasing age. Understanding the impact in terms of mortality of Covid-19 spread is crucial to our calibration, as a society, of the level of risk we are comfortable with,” he said.

In case of backlog reporting, however, states should check and verify the actual date of death and incorporate the number for that exact date, said Bhramar Mukherjee epidemiologist and professor at the University of Michigan’s School of Public Health.

“We have seen blips in excess mortality estimates due to such backlog updates and these fatalities cannot be mapped to timing of infections, causing confusion. This is why accurate death reporting is so critical,” explained Mukherjee.

“Reporting the day of death instead of the day death was reported/registered could solve this problem. As modelers we have been distributing these ‘catch up’ numbers over a time window to smooth our fatality rate estimates. The time lag from infection to death is a key parameter and these anomalies affect our estimates,” she added.

(Edited by Poulomi Banerjee)

Also read: Antibody cocktails, oral pills: These are the Covid treatments available as Omicron surges