Chennai: When Tamil Brahmin priest Ramachandran received an invitation to work in a temple in Ayodhya, his first thought was to say no. His priority was elsewhere—to wrest his temple in Tamil Nadu away from the state government’s control.

In his mind, the state is out to loot Tamil temples of their land, jewels, and rightful earnings. And Ramachandran isn’t alone—his grouse is now part of the new temple freedom movement that has been bubbling in Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Uttarakhand, Odisha, Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, and West Bengal. The epicentre, though, is Tamil Nadu.

“The DMK government is laughing at the state of us Hindus,” said temple poosari, or priest, Ramachandran, adamant that the government is out to ridicule and humiliate Hindus. “They do not care about our pain.”

Temple management in the state has been forged over seven decades of Dravidian social justice politics. It has been held up as a template among many Dalit and OBC groups but has also led to much hand-wringing and souring over time among Hindu groups.

This week, the question of who runs revenue-rich Hindu temples returned to political slugfest. Karnataka CM Siddaramaiah just passed the Hindu Religious Institutions and Charitable Endowment (Amendment) Bill, which mandates the government to collect 10 per cent tax from temples with revenue over Rs 1 crore. BJP minister Rajeev Chandrasekhar called it the new jizya tax, rekindling the troubling public memories of Aurangzeb’s rule over Hindus. Karnataka’s explanation that the money will benefit poor priests in the state is lost in the din made by BJP’s accusation of appeasement politics.

Also read: When did large Hindu temples come into being? Not before 500 AD

Free Hindu Temples movement

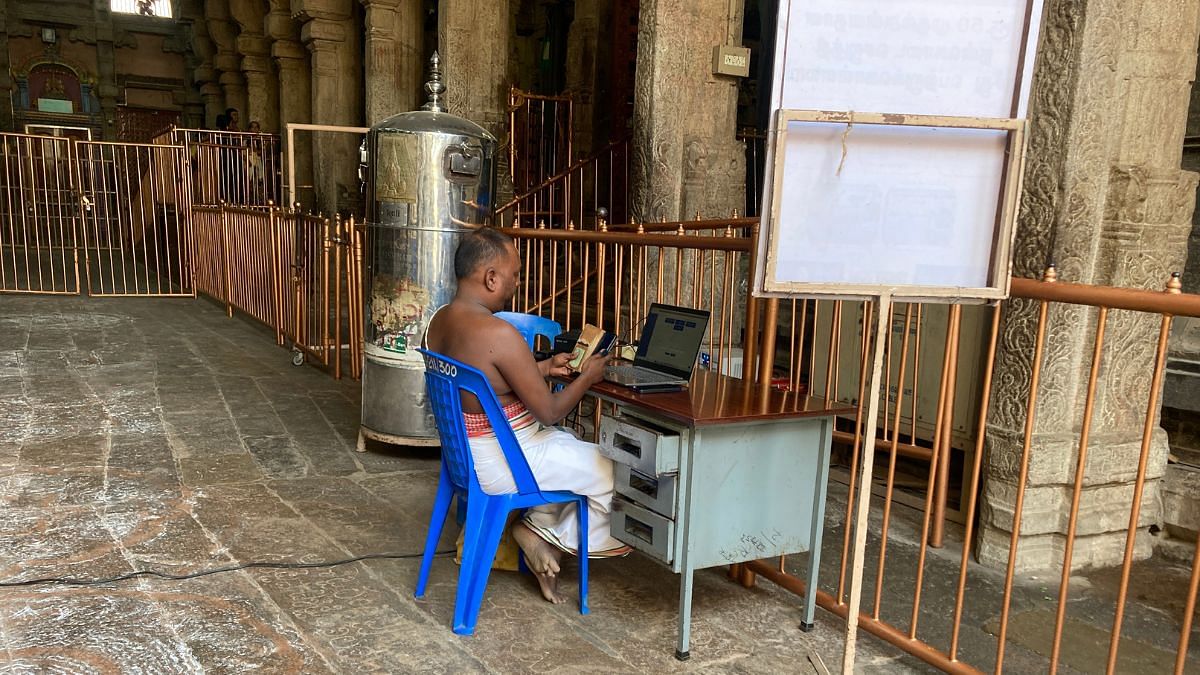

Ramachandran’s reaction is part of a decades-old fight between the Tamil Nadu government and a campaign predominantly spearheaded by the Brahmin community to free temples from government control. The state is home to over 46,000 temples, including some of the oldest and most sacred temples in the country. Other states in India look to Tamil Nadu and its 1959 Hindu Religious & Charitable Endowments (HR&CE) Act as a blueprint for temple administration, but many see the government’s role as direct interference with Hinduism.

The DMK government is laughing at the state of us Hindus. They do not care about our pain.

– Ramachandran, temple priest

Way before Tamil Nadu made temple control a hot political issue, East India Company agents first took over India’s temples and mosques through The Religious Endowments Act 1863. The shrines were seen as a source of wealth and rent for the British Raj.

The state control in Tamil Nadu, however, came after the Dravidian movement in the mid-20th century demanded that the logical step after temple entry was to end the monopoly of Brahmins over temples. The angst and the anger around this boils down to one fundamental question: who gets to decide how temples are run?

On one side is the DMK government and anti-caste activists who insist that temples should be run by the government to cleanse them of casteism. On the other side is the Free Hindu Temples movement, which accuses the DMK government of failing to protect and govern temples and misusing their lands and funds instead. Both sides advocate for the right to manage temple resources — but neither side sees eye to eye.

Periyar made it his mission to end caste-based discrimination in temples, and campaigned for the appointment of non-Brahmin archakas or priests. Several changes that the Tamil Nadu government has made over the past century — like free temple entry, the appointment of non-Brahmin priests, self-respect marriages, and prayers in Tamil not Sanskrit — have been seen as encroaching on the rights of Hindus, and fundamentally altering the nature of worship. The BJP has also entered the fray, questioning why mosques and churches are allowed to be run by Muslim and Christian community members.

“The collective effect of the Dravidian Movement over the last century has been to democratise faith across Tamil Nadu, and not just let matters of faith rest in the hands of a select few, based on heredity,” said IT Minister Palanivel Thiaga Rajan, whose father was HR&CE Minister and whose family is descended from the builders of the ‘One Thousand Pillar Hall’ and the ‘Chithirai Tower’ of the storied Meenakshi Amman Temple in Madurai.

The state draws the highest number of tourists in India, including domestic tourists flocking to visit Tamil temples. In the first quarter of 2023, over 12 crore domestic tourists visited the state.

“Hinduism has flourished in Tamil Nadu because of Dravidianism, not despite it. It is because we have enabled all people to have full and equitable access to the temples, and closed the gap between the people and their Gods, that Tamil Nadu has among the highest number of followers of Hinduism,” said PTR. “Tamil Nadu is the land of temples, but it is also the land of social justice.”

Also read: ‘Hindustan is finally for Hindus.’ Ayodhya Express reaches Ram temple

The case for freeing temples

Activist TR Ramesh is the HR&CE department’s own personal bugbear. He’s single-handedly been trying to hold them accountable and keep them transparent.

The former Citibank professional knows the HR&CE Act like the back of his hand, and is a fixture in court — usually representing himself in the PILs and writ petitions he files regarding the administration of various temples across Tamil Nadu. The front room of his Mylapore home is dedicated to his activism, his desk laden with files and documents — much like the department’s desks.

Ramesh has dedicated the last 15 years to this work, painstakingly combing through centuries of documentation in his fight to prove that temples can work more efficiently if freed from the government’s control.

“Freeing temples will empower them,” said Ramesh. “If you free temples in Tamil Nadu, a thousand institutions dedicated to the welfare of society would come up.”

He argues that the government does not interfere in the appointment of bishops, for example, so they should leave the Hindu faith alone as well.

“The fundamental flaw is that the government is administering temples instead of trustees. The Assembly that passed this act didn’t envisage the government administering temples,” insists Ramesh. “It’s not a question of ‘if not the government, then who else’. It is not meant to be the government. This is a 70-year-fraud.”

Certain provisions of the act—like the government’s power to appoint trustees and auditors, and the commissioner’s power to appoint executive officers at temples—are against the fundamental rights of Hindus, according to him. He also pointed to the “abject failure” of the department to protect immovable properties of temples from encroachers, keeping them from realising their true incomes. According to Ramesh, 18.69 lakh audit objections are pending resolution, piling up from 1986. He also said that ancient temples’ structures and aesthetics have not been taken proper care of, as the government has the discretion to go for lucrative contracts for renovation.

Hinduism has flourished in Tamil Nadu because of Dravidianism, not despite it.

– PTR, IT minister

He’s careful not to take a political side — while critical of the DMK and AIADMK governments, he’s also critical of the BJP and RSS’s agenda to free temples. “The BJP wants to have a Vatican model — they want to control who a Hindu is and how a Hindu thinks,” said Ramesh. “Instead, Hindus should be allowed to think freely, have the right to know what their traditions are, to uphold them and use their resources as they see fit. They do not need a political party telling them what to do.”

Ramesh has taken the Act apart on several occasions, exploring all loopholes and possible exemptions. He’s traced centuries of temple administration from colonial times to Chola times, and has had to reach back into the past to bolster his present arguments.

If you free temples in Tamil Nadu, a thousand institutions dedicated to the welfare of society would come up

– TR Ramesh, activist

One such example is the 1897 Oxford English Dictionary definition of the word “denomination” — an important definition that forms the basis of his entire crusade. The HR&CE Act states that if a group of Hindus can sufficiently prove themselves to be a denomination, then they can take over administration of the temple. This is how the Chidambaram Temple — the largest temple in Tamil Nadu not to be governed by the HR&CE department — is independent of government control. The Dikshitar community were able to prove they are a separate denomination under Hinduism.

The Dikshitars are an exclusive group of Brahmins who have been hereditary trustees of the temple, and also have the right to practise as a priest or archaka at the temple. In 1982, the government tried to appoint an executive office to run the temple but the community challenged the decision—the Supreme Court eventually ruled in their favour in 2014, making Chidambaram Temple a denominational temple.

The government has been eyeing ways in which it can take over the administration of the temple, which Sekar Babu has made no secret of. “Efforts are being made to bring the Chidambaram Nataraja Temple under HR&CE,” he has stated. The Dikshitars and the government have had frequent run-ins — an FIR was recently filed alleging child marriages being conducted within the temple, and the government has objected to the Dikshitars denying worship within the Kanagasabai, a special hall within the temple. There was also a recent case where over 20 Dikshitars were booked for denying a Dalit woman the right to worship within the Kanagasabai.

But the Dikshitars have also dug their heels in, defending their centuries-old presence at the thousand-year-old temple. The deeply religious sect traces its origin to Mount Kailash, and is believed to have been brought to Chidambaram by Lord Nataraja (Shiva) over 3,000 years ago.

To Ramesh, the Chidambaram temple is a model of how temples could be governed by people directly invested in their welfare. To the government, it’s a model of exclusion and mismanagement. The central faultline is caste.

Tamil Nadu is the land of temples, but it is also the land of social justice.

– PTR, IT minister

Also read: MP Congress is courting Hindu priests. But temple land promise is going to be tricky

A department with their hands tied

The HR&CE Department in Tamil Nadu is on the frontlines of this war. They are credited with saving temples from casteist rot, but also stand accused of mismanaging temples and disenfranchising priests.

The department has plenty on its plate. Besides having piles and piles of files — some decades old — to tackle, they’re also subject to slander.

It’s constantly attacked by the BJP and other Hindu Right-wing groups, demanding that they release temples from their control — a demand the department doggedly ignores as it tries to go about its work.

It’s not a question of ‘if not the government, then who else’. It is not meant to be the government. This is a 70-year-fraud.

– TR Ramesh, activist

“Those who are intellectually blind say that the HR&CE department has encroached on temples in Tamil Nadu,” declared HR&CE minister Sekar Babu recently in the state Assembly. “The state government has retrieved nine temple properties worth Rs 700 crore from a section of people who demand privatisation of temples,” he continued, in a veiled attack at the BJP.

The department is large and prestigious, occupying prime property in Chennai’s Nungambakkam and employing over 1,300 people. The building is new and sparkling, with its own temple shrine in the courtyard. It’s a hub of activity on weekdays, with visitors streaming in and out. One large room has a wall full of screens, constantly playing CCTV footage from various temple sites.

But department officials are caught in a complicated web. They’re often maligned by the temple staff they’re sent to administer, having to endure days of abuse and stonewalling. They also constantly have to face scrutiny from other quarters over their activities, which is why the department is taking extra care to be open and transparent.

“All kinds of unfair allegations have been made against us, that’s how we’ve become the butt of jokes. In the process of work, we’re facing slander — and no one helps us,” said an official who requested not to be named. “I tell everyone not to come to this department.”

The same official detailed the obstacles they faced when they were an executive officer at Srirangam temple in Tiruchirapalli. Any change they tried to implement was met with stiff opposition. For example, when they tried to change the way the Vaikunta Ekadasi festival was organised at the temple to make it more inclusive and introduce paid passes, they recall getting hundreds of phone calls within minutes harassing them to retract the change.

One Brahmin priest threatened them and asked if he should remove his sacred thread and work in their backyard as a labourer instead.

At the heart of the matter is rigid and rampant caste divisions. And now, constant cases have trapped the HR&CE department in a litigious limbo.

Officials at the HR&CE department feel handicapped by the judicial system. Cases dealing with encroachment of land take time, especially as they are civil cases — and the department often spends decades fighting over parcels of land. Caught in these cases includes land that the department is trying to recover from age-old leasers — for example, they recently recovered over 2,000 acres of land in the Vedaranyeswarar Temple in Nagapattinam that had been leased to the Salt Corporation of India by the East India Company, which was still paying the same rent.

In another case, hours after the government recovered land belonging to Kasi Vishwanathar Temple in St Thomas Mount, a Vanniyar caste group filed a counterclaim for the land — and the Madras High Court issued a stay on the government’s recovery.

In yet another instance, Ramesh filed a writ petition alleging misuse of Mylapore’s Kapaleeshwarar temple lands and funds that the government now has to defend.

The department is committed to further transparency so that their work can be above board: they now have an integrated temple management system, an app called Thirukkoil, and have even recently started livestreaming the opening of donation boxes. But the pressure on department officials is offset by typical bureaucratic lethargy, which is why activists like Ramesh accuse the department of inefficiency and mismanagement.

“Because of the bad blood, we’re saddened to work as government officers in this department. At least when we’re there, there’s someone to blame,” added the aforementioned official.

The Periyar effect

Temple entry for all was never the end goal in Tamil Nadu — the democratisation of faith was.

Former CM and Dravidian leader Karunanidhi waged a long, legal war to alter temple administration. He led the abolishing of hereditary priesthood, amending the 1959 HR&CE Act in 1971 to do so. Other eventual reforms included requiring temple trustee boards to include one woman and one Dalit amongst its five members, and he also extended the Land Ceiling Act to temples.

But detractors of the reforms took to the Supreme Court, further tying up the issue in legal knots. One notable judgment that has thrown a spanner in today’s works is a 1972 Supreme Court judgment abolishing the hereditary rights of priests — while simultaneously upholding the DMK government’s 1971 amendment of the act as “essentially secular.”

“Operation success; patient dead,” wrote Periyar in an editorial for Viduthalai after the judgment, a year before his death. The act was secular in the eyes of the apex court, but the resistance would continue for decades.

The fervour around the issue has been more intense during DMK governments when compared to AIADMK governments, bleeding through the back-and-forth political climate whenever the courts took up matters relating to temple administration. The current HR&CE minister, Sekar Babu, himself moved from the AIADMK to the DMK.

DMK supremo Karunanidhi made another attempt in 2006 to fulfil Periyar’s vision: he introduced an 18-month course to train archakas from all castes to be able to work in temples. Of the 240 people who enrolled in 2007, 207 graduated the following year — only to find themselves unemployed. Brahminical temples were unwilling to let them work. The training school was soon rendered non-operational after a petition was filed by a Hindu group, the All India Adi Saiva Sivacharyargal Seva Sangam. During AIADMK’s tenure, CM Edappadi K Palaniswami appointed two non-Brahmins archakas to non-agamic temples, but made no further appointments.

My family and I were harassed with threatening calls, accusing us of polluting a sacred space

– a non-Brahmin archaka

“The government is there [in temples] by fraud, constantly unnecessarily interfering in the affairs of temples,” said Ramesh. The Tamil Nadu government just doesn’t seem to leave temples alone — they’re always trying to meddle, tweak, and update administrative affairs.

Since the HR&CE Act was introduced, it has gone through 58 amendments as of 2022.

In 2021, 100 days after the DMK came back to power, Karunanidhi’s son and current chief minister MK Stalin appointed 23 non-Brahmin archakas across temples in the state. As of 2024, only two of these 23 priests are still working. The others have all withdrawn, citing humiliation and ostracism by Brahmin archakas.

“I was insulted every day. I was not allowed to enter the sanctum sanctorum, and made to do menial work. I was not given the right to conduct rituals for devotees, and was even denied private opportunities. My family and I were harassed with threatening calls, accusing us of polluting a sacred space,” said one non-Brahmin archaka who requested not to be named. He now works at a small private temple away from his family — he barely earns enough to save, but his meals and stay are taken care of.

For anti-caste activist and political commentator Maruthaiyan, opposition to the HR&CE department and the government’s directives threatens the revival of Brahminical oppression. Furthermore, he sees the argument over denominations as a proxy for caste — the Hindu Right interprets caste horizontally and not hierarchically as graded inequality, according to him.

“The struggle is against caste hierarchy. The temple is an institution to safeguard this social system,” said Maruthaiyan, recalling an instance in which his organisation, the People Rights Protection Forum, came to blows with priests at the Srirangam temple in 1993, when Dalits were not allowed to pray in the sanctum sanctorum.

They had been trying to place photographs of Ambedkar and Periyar within the temple, signalling the welcome of non-Brahmins into the temple. Eventually, the Brahmin priests backtracked, and no cases were filed.

Also read: Tamil Nadu’s temple entry problem is spreading: Gounders, Thevars say ‘our god our temple’

The political climate

Outside the Srirangam temple stands an infamous statue of Periyar. It carries his famous words: “There is no god, there is no god, there is no god at all. He who invented god is a fool. He who propagates god is a scoundrel. He who worships god is a barbarian.”

The controversial statue found itself on the BJP’s manifesto: Annamalai, state president of the BJP, swore that removing the statue would be its top priority if they came to power in the state.

“It’s completely unnecessary here,” says Deepak Rengarajan, protocol officer of BJP Tamil Nadu and head of their Trichy chapter, gesturing at the statue. “This is an ancient, sacred temple and it is against its beliefs to have this statue saying there is no god. Would it be such an important temple if people believed that?”

Rengarajan worships at the Srirangam temple regularly, and is eager to point out how government-appointed priests control the flow of devotees and therefore the flow of money. Special, fast-track darshans are more expensive than regular darshans, and he wonders often how much of the money is making it into the temple coffers. At the same time, he believes that only Brahmins should be priests as they are the only ones who can truly uphold the sanctity of the temples. His distrust lies with the DMK government, not with the centuries-old social hierarchy.

“By capturing the temples, the BJP thinks they can control the Hindu community. They’re not interested in the properties of the temple — they’re interested in capturing minds,” said Maruthaiyan, insisting that the BJP’s politics has no takers in Tamil Nadu. “Belief in God does not equal belief in caste supremacy.”

But the BJP’s rhetoric is already having an insidious effect on society, according to Maruthaiyan. He pointed to recent litigation in the fray: In January, the Madurai bench of the Madras High Court said that non-Hindus were not allowed inside the Palani temple’s premises, after a Hindu toy seller filed a case against a Muslim fruit seller and his family. The fruit seller was visiting the temple to show his children a tourist spot, which the toy seller petitioner took offence to. In a magnanimous addition, the petitioner said that non-Christians should also be banned from churches and non-Muslims from mosques. The high court, in turn, said temples cannot be seen as a picnic spot, and suggested maintaining a record of the faiths of all visitors.

Belief in God does not equal belief in caste supremacy.

– Maruthaiyan, anti-caste activist and political commentator

Calling it an assault on India’s syncretic tradition, Maruthaiyan said that the Hindu Right is using caste pride to breach Dravidian ideology in Tamil Nadu. This is why the emphasis on God over humanity — and who gets to speak for which God — is at the basis of the “free temples” movement.

“Free temples from whom? Who are the representatives of Hindus? Is it not the government they elect?” asked Maruthaiyan.

The BJP push

In 2021, the Pushkar Dhami-led BJP government in Uttarakhand restored the control of temples to priests and temple trusts by reversing a controversial measure. The highly sensitive move set off a debate among many at the time, and the BJP had a political issue on its hands.

Centuries after India’s revolutionary temple entry movement, a new kind of churn is underway, helmed by the BJP.

“Hindu groups’ demanding the exit of government control over temples in several states should be seen in the light of Hindu awakening and assertion,” said Seshadri Chari, the former editor of RSS publication Organiser.

Right before the Karnataka Assembly elections last year, the BJP promised to grant complete autonomy of temple administration to devotees, removing them from the government’s control — a shot in the dark, as the Congress formed the government instead.

Since temple administration comes under the state list — and to some extent the concurrent list — the BJP can keep the issue brewing at the state level, but can’t tackle it at the central level.

“This could become an issue for the BJP at the state level,” said Chari, “For example, in Karnataka there is resentment over the government’s idea of taxing temples with more than one crore income. The BJP will benefit from this tax on Hindu temples.”

BJP members also privately say that if they push at it too hard, it may bring political risks too, especially in the south. It has taken decades for the BJP to shed its Brahmin-Baniya tag and foray into OBC, Dalit and tribal communities. Granting autonomy to temples could potentially resurrect Brahmin priest domination, and trigger caste wars, say social commentators.

But temple politics is back in more ways than one now. One is BJP’s push for reclamation projects like the Ram Temple in Ayodhya, run by the Shri Ram Janmbhoomi Teerth Kshetra which includes RSS and VHP members. Reclaiming Gyanvapi in Varanasi and Mathura are next. The other reform is to free temples from the government’s clutches and return them to trusts and priests. All this as BJP state governments also go about conceiving and implementing temple economic corridors.

Also read: Tamil Nadu temple wars: How BJP’s new ‘spiritual wing’ is taking on DMK

The way forward

The fight against Sekar Babu and the HR&CE Department is personal to Ramachandran.

“They only want to take away all the wealth we have,” he said vehemently. He dismissed the incidents of priests pawning temple gold or the deity’s adornments, as temporary hardship. “The government hasn’t paid our salaries in months! What else are poor priests supposed to do?”

The ire over the issue is directed at the elected DMK government, with many accusing it of systematically dismantling temples as sites of Hindu pride. The DMK, too, has been careful to situate it as a Brahmin issue — and thereby not malign the larger Hindu community in the state.

Free temples from whom? Who are the representatives of Hindus? Is it not the government they elect?

– Maruthaiyan, anti-caste activist and political commentator

“People say the HR&CE department is not functioning well. Show me a government department for which a similar criticism cannot be justifiably made,” PTR asked. “If sub-optimal functioning is the basis for privatisation, can all of the government be improved by privatisation? And if so, who will be the new ‘private’ owner? And can they guarantee efficiency?”

The collective aim to democratise temples and bring faith to all regardless of caste should be lauded, and not falsely portrayed as “Anti-Hindu” he added.

The irony is that the Madras High Court — the default arbiter of the issue — stands on temple grounds. It was built by the East India Company on land that belonged to the erstwhile twin temples of Chennakesava Perumal and Chenna Malleeswarar. Once a year, the court is allegedly shut down for the temple to carry out purification rituals, according to HR&CE officials.

“This is the environment we live in,” said an HR&CE department official, while closing a file on an encroachment case. “Rationality, even in law, pales in front of faith.”

This is the first article in a series about the tug-of-war between States and temples over control of wealth and worship. Follow the series on this new temple freedom movement here.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)