Firozabad: It was a cold winter day in 2019. The bangle city of Uttar Pradesh had fallen silent. Firozabad was under curfew. Factories were shut down. Only the police and the CAA-NRC protesters were out on the streets. But six fleeing bangle workers and a farmer were shot dead.

Almost four years later, nobody knows who killed them. “Which rioter shot which men, who knows. And there is no possibility of knowing it in the future either. There is no point in continuing the investigation,” the UP police said in a report.

The families of the deceased claim it was the police who fired the shots, but their voices were muted. The police ignored them. They were allegedly forced to sign blank witness statements. Some of the FIRs make no mention of bullet wounds. Finally, in June this year, after filing protest petitions challenging the reports, the mother of one of the deceased men got a chance to tell the court how her son died on 20 December 2019.

Unlike the anti-CAA-NRC protesters, these seven men are not framed in heroic protest narratives. They were just men who happened to be at the wrong place at the wrong time and got caught in the firing.

“The police were firing ferociously at the people. A bullet hit his temple, right between the ear and the eye,” Rani said, showing the photographs of her husband Shafiq’s injured body on a hospital bed before he succumbed to his injuries. She’s waiting for her turn to go to court and speak for her husband. Shafiq was crossing the street in front of his home when he was shot.

“We [my daughter and I] were hiding on the roof and we saw with our own eyes that the police were firing. Today if the police are saying they didn’t do it, at least tell us who killed him,” said Rani.

A day before the violence, Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath thundered from the stage: “They [protesters] have been captured in video and CCTV footage. We will take badla (revenge) from them.”

The police did comb through CCTV footage but to identify protesters who vandalised police stations and damaged chairs, tables and ceiling fans. They said they could not recognise the perpetrators who fired the shots at the seven men. Opposition parties have moved on, exhausted human rights activists have left, and the media spotlight has turned off.

Only their unexceptional, siesta-loving lawyer Sageer Khan is fighting for them.

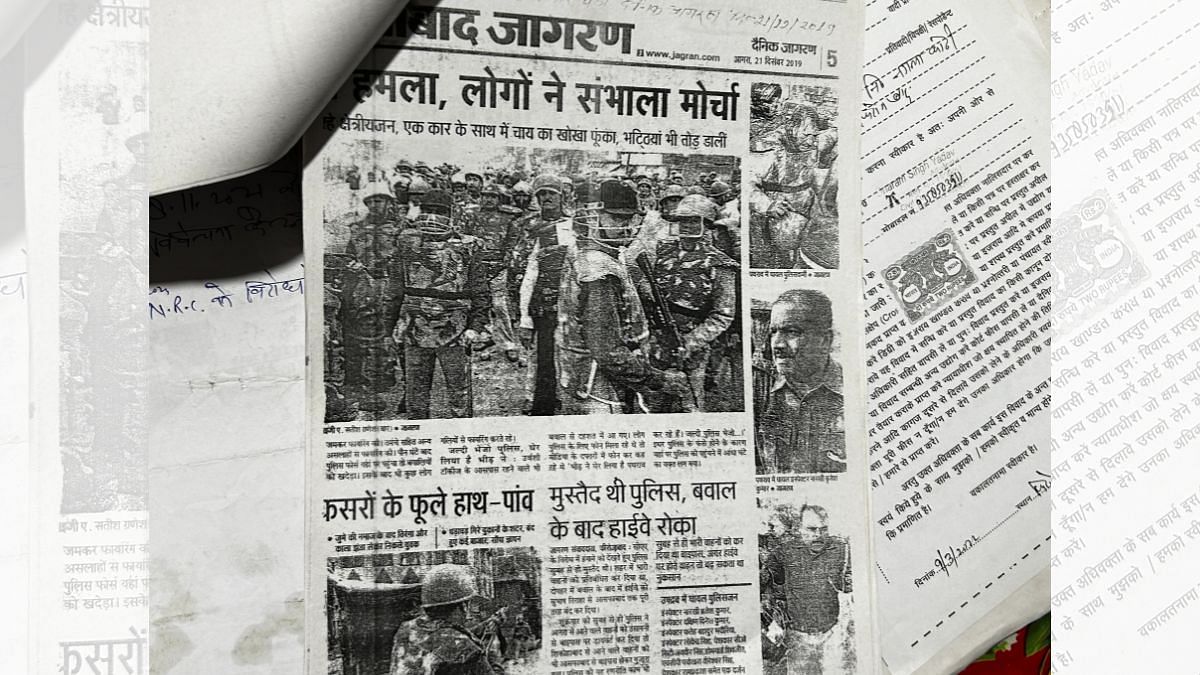

“A man’s life is cheaper than the cost of a police baton, fan and cooler? The police can even trace a stolen slipper from a religious site, but they can’t use the CCTV footage to nab killers?” Khan asked matter-of-factly. “The killers are one of their own. The newspapers published images from the violence site where SP city, CO city, and SHO of Rasoolpur police station were present. All of them fired.”

Khan cannot reconcile the police’s thoroughness in detailing the damage to property with their failure to identify the killers. Through protest petitions, he challenged the police’s closure reports and got his clients another shot at justice.

“The police have successfully counted the cost of the chairs, tables and ceiling fans damaged during the protest. They have prepared a list of 29 Muslims responsible for this damage. But they are unable to find who killed these seven men?” he asked.

Also read: Young women are jumping into wells in Barmer. It’s a suicide epidemic

Bystanders caught in fire

On 1 June, Shamsun Begum walked nervously into the district court in Firozabad, the first complainant to record her statement before the magistrate. She borrowed money from a relative for the tempo fare from her house to the court. It was an important day.

After more than three years of fighting, she and others won the right to be heard when a local court in 2022 rejected the closure reports in five cases and ordered the police to investigate the death of the sixth bangle worker. “There is a contradiction between the statements made by the complainant and evidence on record,” the court had ruled.

Her son Muqeem, 20, left for the bangle factory at 8 am on 20 December 2019 and never came back home. A relative found him on the road, bleeding from a bullet wound near his underarm. He died three days later.

“We wrote whatever the police forced us to write. But in the later months, they thrashed and abused us,” said Shamsun, who lost her husband to cancer last year.

But during the hearing in June, Shamsun forgot the year her son was killed. The court gave her another date (3 July) for her next statement.

Away from the police and court, in their one or two-room houses in the dark congested lanes of Firozabad, the surviving family members continue to search for the most inconvenient answer: who killed Shafiq, Muqeem, Arman, Mohd Abrar, Mohammad Haroon, Nabi Jaan and Rashid? As they chase the ghosts of the past, they live on the money they earn making bright, colourful bangles.

None of the seven men were CAA-NRC protesters. They were bystanders or those scurrying for cover and heading home. Their families say they were caught in the police firing. But now the police wouldn’t own up to it.

On 20 December 2019, Shafiq (42) was trying to reach his house. With growing unrest in the town, his factory had pulled down its shutters. As he was crossing Naini Chauraha, a major intersection in Firozabad, violent clashes between protesters and police broke out. He had almost made it. His wife Rani, now 41, and their daughter were on the rooftop tracking his movements. They claim they saw the police firing in his direction, and a bullet hitting him.

“The police were firing like in films—indiscriminately. People started running to their homes to escape the bullets,” Rani told ThePrint. She remains steadfast in her truth. She recounted the same events in December 2019 while sitting in the ICU ward of Safdarjung Hospital in New Delhi, waiting to hear from the doctors treating her husband. And again, to police, lawyers, judges, and journalists.

The same day, 30-year-old Haroon, a farmer, crossed Naini Chauraha on his way back to his village, Naglamulla, which is on the outskirts of Firozabad. It was a good day; he had sold one buffalo at the cattle fair for Rs 36,000.

And then he fell. While bleeding on the road, he called his mother.

“He said he had been injured by a police bullet. He shared the location where he was lying,” Naima Begum (60) recalled. He was alive, bleeding on the same spot when his uncles and cousins arrived an hour later. The first thing he did was give them the Rs 36,000. They took him to a district hospital and then to AIIMS in New Delhi where he died a few days later.

Between 3 pm and 6 pm on 20 December, seven people were fired upon at Naini Chauraha and Urvashi Tiraha, another intersection barely 2 km away. Of the 24 reported deaths in UP during the CAA-NRC protests, Firozabad recorded the highest toll—seven deaths. Some died on the spot, others in hospitals.

Also read: Pulwama widows’ fight in Rajasthan has exposed an age-old secret—chura pratha exploitation

Mystery of FIRs

Six FIRs were registered at three different police stations. The families allege that the police had fired at the men. The victims did not know each other. But four of the six FIRs were identical in one omission: they made no mention of bullet injuries.

And all named the accused as “an unknown crowd”.

“Not only were some FIRs delayed, but the families were also forced to sign on blank papers,” Khan alleged.

Haroon’s FIR states he was injured in a stampede at Naini Chauraha. In Muqeem’s FIR, police say he came home injured at 5:30 pm, without mentioning the nature of injuries or gunshot wound on his chest. Shafiq, too, officially died of stampede-related injuries. The FIR on Abrar’s death says he was found injured, but other details, including the location of his death, are missing. According to his family, he had died of bullet wounds at Naini Chauraha.

The FIR for Nabi Jaan states he died of a bullet wound at Urvashi Tiraha, but rioters were blamed for it. Only in Arman’s case do the police acknowledge the possibility that the bullet could have come from the police. “We don’t know if the bullet came from the rioters’ side or the police’s side,” reads the FIR.

In Rashid’s case, the seventh man who died in the firing, the police never registered an FIR. “On 25 December 2019, I went to the SSP to submit an application, requesting to register an FIR. But no action was taken. I also registered an online complaint 25 December but there has been no follow-up,” said his father Noor Mohammad, who approached the district court 10 January 2023 to take cognisance of the matter. The court rejected his application in March 2023. Mohammad and Khan are now planning to approach the high court.

Kumar Ranvijay Singh (SP Rural), the nodal officer for the CAA-NRC cases, refused to comment on the accusations made by the victim families and lawyer Sageer Khan.

“We are still investigating,” was his only response to how medical records were omitted from some of the FIRs.

Sachindra Patel, SSP Firozabad in 2019, had denied any firing from the police’s side. “Police are examining CCTV footage to identify the miscreants and help the victims,” he said.

Almost everything about the anti-CAA-NRC protests stops at a story of delayed justice and families trapped in an endless wait.

Hundreds of activists languish in jails across India, waiting for trials if not bail—a far cry from the heady days of the 2019 protests when Varun Grover’s Hum Kaagaz Nahi Dikhayenge became a protest anthem across India. When Bollywood actors and activists found common ground in Mumbai and the women of Shaheen Bagh took the lead in New Delhi. But by February 2020, ahead of former US President Donald Trump’s visit to India, there were violent communal clashes in Delhi.

And by March 2020, the movement ended with a whimper when Prime Minister Narendra Modi called a nationwide Covid lockdown. The families were left with the debris and devastation the protests and police response had left on their lives.

It’s been three and a half years, and the Indian government is yet to frame rules under the CAA-NRC.

Also read: 2 clerks, 1 director, 1 room—AIIMS Darbhanga a story of political rush to announce & forget

Recovery of damages

The police took 11 months to file the closure or final reports in the six FIRs. In both the FIRs and final reports, the accounts of relatives recorded by the police are almost identical to each other.

“Thousands of Muslims had gathered to protest against CAA-NRC. The protest turned violent. They pelted stones and fired in the open. We don’t know which rioter’s bullet killed which civilian,” read one of the final reports filed in a Chief Judicial Magistrate (CJM) court in November 2020.

Similar sentences were used in other cases as well. But what they conveyed through their reports is a tardy, half-hearted investigation and a staggering sense of fatigue with the cases.

“Much time has passed since the incident. People have blurry memories of the faces of perpetrators. There is no possibility of identifying them in the near future. Thus, there is no point in investigating the case,” stated another closure report. Even the CJM court rejected five of the final reports. It also ordered the police to re-investigate Shafiq’s death based on the arguments advocate Khan made.

The protest petition alleged that the police wrote the FIR arbitrarily. It also alleged that the police fired at Shafiq after Rasoolpur police station SHO VD Pandey shouted, “Goli maaro saalon ko. (Shoot them).”

In August 2020, when the public gaze had shifted from protests and petitions to the pandemic, the Yogi Adityanath government enacted the Uttar Pradesh Recovery of Damages to Public and Private Property Act 2020. Under the Act, the state government set up three tribunals in Meerut, Prayagraj, and Lucknow to take account of the damages.

The police prepared a detailed report based on video clips, CCTV footage, and an SIT report. Twenty-nine persons (all Muslims) are charged for the damage of property worth Rs 15,93,000 during the CAA-NRC protests. In its lengthy list of damages, the UP police itemised, among other things, l50 batons, four fans, two coolers, two cupboards, two torches, six chairs, a Sony digital camera, and a Samsung mobile phone.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)