Kochi: Students were scattered in and around campus. Some were asleep in their rooms. Others were drinking milkshakes outside. A mundane night at Maharaja’s College, Kochi, Kerala, came to a startling halt at 11:30 pm. Naasir, a Students Federation of India leader and Student Union secretary, had been stabbed.

“It was clearly a pre-planned attack. They pushed me to the ground and punched me. I tried to run away, but one of them came and pushed me. Then they attacked me with swords,” says Naasir, who received 32 stitches and is currently undergoing physiotherapy for a half-severed finger. “They’ve been doing this since the election. If they attack us, we will attack back.”

Campus politics in Kerala used to operate under an Omerta of sorts, where violence worked in tandem with silence – everybody, from the Congress to the Communists, was complicit in a tit-for-tat cycle of reprisal attacks. But now, with the upcoming Kerala Assembly elections and the talk of Hindu Right-wing groups making inroads in campuses, the stakes are higher than ever and each attack is getting amplified nationally.

Now, the SFI, the student wing of the CPI(M), is grappling with a three-party opposition that has banded together—the Congress’ youth wing Kerala Students Union (KSU), the Fraternity Movement affiliated with the Jamaat-E-Islami Hind, and the Muslim Students Federation (MSF). And Maharaja’s College, which incubated leaders like AK Antony, is now the epicentre of campus violence. Last year’s election marked a first since 2018, with a KSU member winning a single seat. It was enough to send the college, an age-old SFI fortress, into a seething frenzy.

The events leading up to Naasir’s stabbing appear almost choreographed. Four days before the incident, students from the college’s economics department, who were travelling from Ernakulam to Elavoor, were attacked inside the train. This set off a new cycle. The next day, an assistant professor with the Arabic department was assaulted by a member of the Fraternity Movement. And on 18 January, hours before he was stabbed, the contents of a dustbin were emptied out on Naasir while he was practising for the university’s drama festival.

It all testifies to how deeply politics is woven into the fabric of student life in God’s Own Country. The personal, the social, the cultural — everything is political. Violence is part and parcel of the game. Notices by the Kerala High Court based on a public interest litigation seeking to ban student politics on campuses, multiple suspensions, on and off-campus attacks, and the disruption of academic life—none serve as deterrents.

Protests are a weekly activity in the campus. Deeply affected by national politics, there have been regular gatherings renouncing the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) and the inauguration of the Ram Temple in Ayodhya. Massive protests took place over the violence in Manipur. Students have watermelon emojis in their WhatsApp statuses, a new-age digital symbol of Palestinian resistance.

“Every activity is for a political reason,” says Naasir.

The Maharaja’s College campus has been restive since 18 January. College gates slam shut at 5 pm, though students simply clamber over the gate to get back in or out. There are SFI banners everywhere, with students claiming that posters and placards representing other parties have been removed.

“Bloody Khan, remember, this is Kerala,” reads one poster, a reference to Kerala governor Arif Mohammad Khan. There is a flag with Argentine Marxist revolutionary Che Guevara’s picture, and a red SFI logo on a blown up map at the college gates.

Also read: 10 dirtiest cities are in ‘waste Bengal’. Kolkata to Kalyani, people clip noses, accept it

Crumbling facade of normalcy

Students make jokes about how “well-located” their college is. “We’re so privileged. There’s a hospital to the left, a court to the right, and a police station in Subhash Park,” says Christina, a final-year history student. They need all three, and easy access comes in handy.

The SFI has gained a reputation as the harbinger of brute force, partly due to the electoral and cultural pull it holds. Out of the 3,000 students at Maharaja’s College, 1,700 are SFI members. Students such as Naasir treat the college as a stepping stone, an entry point into formal politics.

The usual fare of protests is part of the territory, but Naasir’s attack was accompanied by a great deal of media scrutiny. “The vicious circle of political violence on Kerala’s campuses”, “Rebels without class: Kerala’s higher education sector grapples with persistent campus violence,” were some of the headlines. “Maharaja’s is always the poster child,” reads a comment on a subreddit. The college was shut for about 10 days. Some students remained on campus, but classes were suspended.

It marked another first in the college’s over 200-year history. Even during the Emergency, classes continued and there was a semblance of normalcy. But over the last six months, bit by bit, that facade is crumbling.

Violence shouldn’t find any place in student politics. This is the party’s firm belief, says MA Baby.

“No student has ever been killed by the SFI. But SFI leaders have been killed by other parties, with the help of goons from outside,” says MA Baby, CPI(M) politician, former SFI leader, and former Minister of Education of the state, referring to the death of SFI leader Abhimanyu. In July 2018, the BSc chemistry student and SFI leader was allegedly stabbed to death by student activists from the now-banned Popular Front of India. In the six years since the fulcrum of the SFI’s electoral campaign has been Abhimanyu’s murder and memory.

“Violence shouldn’t find any place in student politics. This is the party’s firm belief. However, factions of the society and media often try to paint the SFI as a source of violence and unrest. It’s a travesty of truth,” MA Baby adds.

But then, the KSU, affiliated with the Congress, spouts a similar ‘non-violent’, ‘no first-strike’ mantra. “When violence is used against KSU, the party will fight back for its existence,” says Aloshiuos Xavier, the union’s state president. “But we will never initiate violence.”

Regardless of their party leanings, students tacitly acknowledge that violence comes from all sides. “There are pros and cons to student politics. The violence is one of the cons,” says a student on the condition of anonymity.

Christina isn’t part of any political party. However, she mentions being pressured by all four parties to join in her first year. She reviewed all, and realised that she wasn’t interested in any. But she is quick to clarify that just because she isn’t a party member it doesn’t mean she isn’t aware of the ongoing events or that she isn’t political.

“You’re not a part of Maharaja’s if you haven’t seen a fight or cops entering the college. There’s nothing to be scared of,” says Christina.

Powerless teachers

Seated in the library, a professor speaks in hushed tones. He says he feels powerless, rueing how pointless his position is. He occasionally looks up to check the CCTV camera behind him. He has come to fear students.

“The teachers have no authority here. Only the students have authority,” he says. His fear isn’t a figment of an overactive imagination. The assistant professor from the Arabic department was allegedly stabbed by a final-year student, who blamed him for suspending another student.

This is an SFI majoritarian campus,” says Maharaja’s College professor.

The faculty at Maharaja’s College has a litany of complaints. Some students have never attended a single class, and the forging of attendance to take exams is frequent. The students falsify attendance records by citing union activities. They don’t show up for internal examinations. And even when they are given leeway–15 extra days specifically to attend classes so they can meet the minimum requirement, they don’t.

“They [the SFI] don’t want the campus to have a healthy academic environment. Often, when we conduct classes—they walk out, saying they have some kind of union programme,” the professor adds. “This is an SFI majoritarian campus.”

PM Arsho, the state secretary of the SFI is 29 years old. According to the guidelines by the University of Kerala, there is a cap on how old student politicians can be–no older than 23. But Arsho is still a student at Maharaja’s College. He also has several criminal cases against him and is currently out of jail on bail.

“Arsho didn’t have any attendance but we had to let him take exams. There’s no scrutiny by the controller of examinations. That’s the problem,” says a former principal of the college who did not want to be named. According to teachers, both current and former, there’s a “slick nexus” at work—between SFI leaders, teachers sympathetic to its cause, and the CPI(M)—which gives ‘students’ like Arsho free reign.

The former principal says that he tried to enforce certain rules and regulations during his tenure but failed. Naasir was attacked late at night, and some of the perpetrators, members of the gang, were outsiders. Days after the attack, Sheela Beevi took charge as the new principal of the college. She has been closing the campus gates at 5 PM, but it does little to keep students in and others out. ThePrint has reached out to Beevi, the story will be updated with her comments.

Maharaja’s College has had 15 principals in seven years. “I’m one of the first principals [in the last 7 years] who made it past the 1.5-year mark,” says the former principal. He still visits the college from time to time, and students come up to him—asking for advice, airing grievances, and talking about the overall sorry state of affairs on campus.

“These are students who are studying well. They come from poor families. They’ve come here to get an education, to understand life in a big city. They also work part-time. They have dreams and aspirations,” he says. About 90 per cent of the union consists of students from Idukki and Malappuram districts. Many of them are first-generation college students.

The college is now filled with fear, says former principal

K Aravandakishan was a student at the college in the 1950s. He returned to his alma mater in the 1970s as an economics professor and then went on to become the college principal. He was an active member of the Old Students Association, and the Teachers’ Association, and used to partake in campus activities on the regular. Now, put off by the intensity of the violence and what he claims is the withering away of “true” leftist ideology, he refuses to enter the campus. However, he also doesn’t know if he will be let in.

“We used to have an impartial attitude toward events on campus. We used to cooperate with the college. But then everything turned political,” Aravandakishan says. “The college is now filled with fear.”

Culture of politics

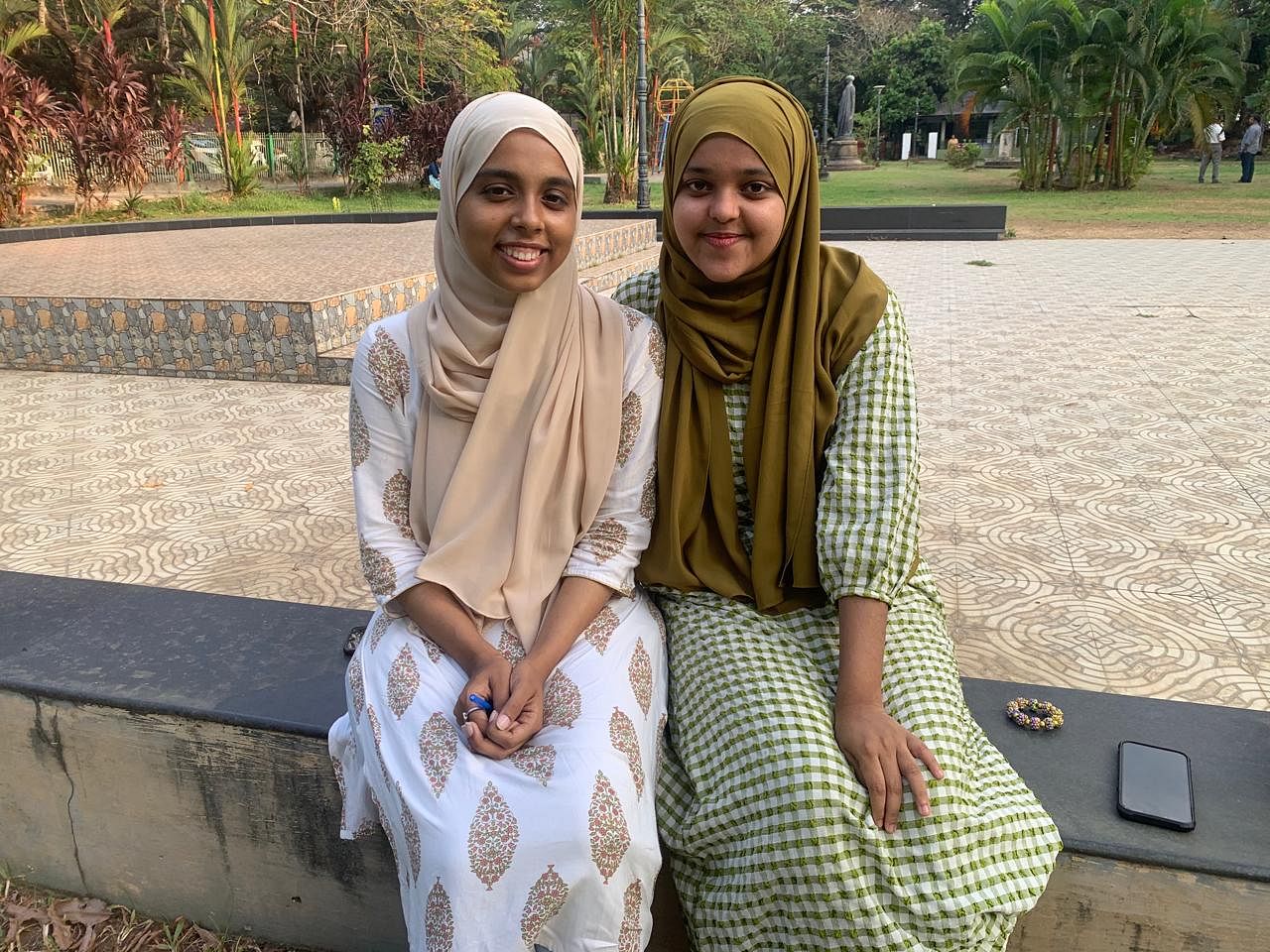

If the professors are fearful, students remain undaunted. Christina says she has accepted the violence as part of campus life. Rida Islam, on the other hand, operates differently. She says she can’t live in fear, and circumvents it by making her politics known. The SFI is against identity politics—the party stands for homogeneity and equality for all. Rida calls it a “double standard.” She can’t extricate her politics from her identity as a Muslim woman.

“How can I separate my identity as a Muslim woman from my politics?” says Rida.

She, who is part of the Fraternity Movement, has contested elections all three years of her college career.

“Everyone is all about communism. But they hide their identity. There’s a lot of Islamophobia in Kerala and the Fraternity Movement sides with those who face it,” she says.

According to the SFI, the Fraternity Movement and the Muslim Students Federation are communal parties capitalising on identity politics and spreading hatred rooted in religion.

“Whenever I speak to first-year students and try to make friends with them, the very next day, SFI people won’t talk to me,” Rida says. “They always bring up the Muslim stereotype.” Sitting next to her, her friend Bushara chimes in. “They don’t talk to me either. That’s because she’s my best friend,” she says.

Violence has shaped our college lives, says Bushara

At Maharaja’s College, political leanings often trump friendships and the regularities of college life. The campus is divided on party lines. SFI, KSU, MSF, and Fraternity Movement members study the same subjects, are of the same age, and mostly come from the same districts. However, for the most part, SFI members aren’t friends with students from the other parties.

“All of the violence, this is the story of our batch. This is what has shaped our college lives,” says Bushara.

Both Rida and Bushara were named by the SFI as two of Naasir’s many attackers. It was a scary time, but now they laugh at the implausibility of the claim. “It was only because we were outside the campus. They were asking why two girls would leave the campus so late,” Bushara says, rolling her eyes.

Naasir’s attack has metamorphosed into a campus-wide urban legend. There are multiple tales and theories about who the attackers were and how many — the numbers tend to vary, and technically, no one actually knows who attacked him. According to Naasir, the attackers were dressed in black, and their faces were covered. He also claims that they were members of opposition parties, accompanied by “thugs from Fort Kochi.”

“It could have been anyone. They have enemies everywhere,” says Bushara. Rida nods in agreement.

The events taking place across college campuses in Kerala appear to be straight out of a movie. But in fact, it’s the inverse—films have taken inspiration from all that unfolds on these campuses.

Students at Maharaja’s College are aware of the position their institution holds in the overall political scenario, as well as the role that campus politics plays in the state’s popular imagination. Nikhil Krishna, a film enthusiast who happens to be studying commerce, excitedly refers to Oru Mexican Aparatha, a 2017 Malayalam film starring Tovino Thomas, known for cementing his position as a star. Set in Maharaja’s College, it chronicles life and love against the all-consuming backdrop that is campus politics. There is tension between the two parties, riffs on the SFI and KSU, and leftism takes centre stage.

But there is a difference between real and reel life. “It’s not really like that though. There is violence on campus, but not that much,” Krishna says with a smile. Classmates (2006), starring two of Kerala’s most well-known actors, Prithviraj Sukumaran and Kavya Madhavan, is another recreation of the heady, terse atmosphere that college students treat as commonplace in Kerala.

Krishna is one of those students who believes in boundaries. An SFI member, he ensures his political rivalries don’t seep into the classroom. “I believe in the real left. I read Marx, and I try to be diplomatic,” he says. “I try to act of my own accord and not get swept up by violence.” Naasir is his friend, as is a KSU member who is also his classmate.

Student politics pipeline

The Kerala government wants the state to emerge as an “educational hub”, and is encouraging foreign universities to establish campuses in the state. It’s an attempt to retain homegrown talent. But no foreign university will not tolerate or condone such violence.

“We must understand that foreign universities coming in means that institutions will be privately funded and will have no social obligations towards our country. Profiteering is the sole motive,” says Shajar Khan, head of the Save Education Committee in Kerala.

TP Sreenivasan, former head of Council for Higher Education of Kerala, explains that in the current ecosystem, the entry of foreign universities is unlikely, let alone their success. “In their heart of hearts, the government wants students to stay and agitate. They’re not very congenial towards change,” he says.

He recalls arranging for American students to spend a semester in a Kerala college. “They were supposed to stay for six months. They left in one. There was no meeting ground. Both sets of students were horrified.”

None of the students ThePrint spoke to want to remain in their home state. Most of them want to go to Delhi University.

Teachers at Maharaja’s College stress the importance of a balanced life; a combination of politics and academia. There’s also the belief that student unions function as “satellite” organisations of their parent parties, involved more in outreach programmes and less in campus issues.

“I’m in my third year and I still haven’t received my ID card. The union should be helping me,” says Christina. She has approached them multiple times.

Teachers worry that the political leaders of tomorrow, for whom Maharaja’s College is an incubator, will be weak–going by how the college has dipped in rankings. The academic environment isn’t conducive to creating wily politicians or citizens who excel in their fields, said a professor who did not want to be named. Maharaja’s College is far cry from its glory days of yore. Former Defence Minister AK Antony, actor Mammootty, and physician Mary Verghese, among others, are alumni of the college.

Politicians, however, are still convinced of the college’s reputation as an incubator for future leaders. “It’s true. There are many competent, studious, militant students graduating to the political party,” says MA Baby. “We consider SFI to be a very influential body for students. So we appreciate what the SFI does. We see it as an active democratic organisation.”

Naasir is ready to study law, a profession that he believes will embellish his political ambitions. And he is going to do it while staying active in the SFI. However, a number of his peers say they are “finished” with Kerala, and are looking to pursue higher education in northern states. Delhi is a clear favourite.

Also read: Bengaluru museum is making science artsy, buzzy. And it won’t stop changing

University of monsters

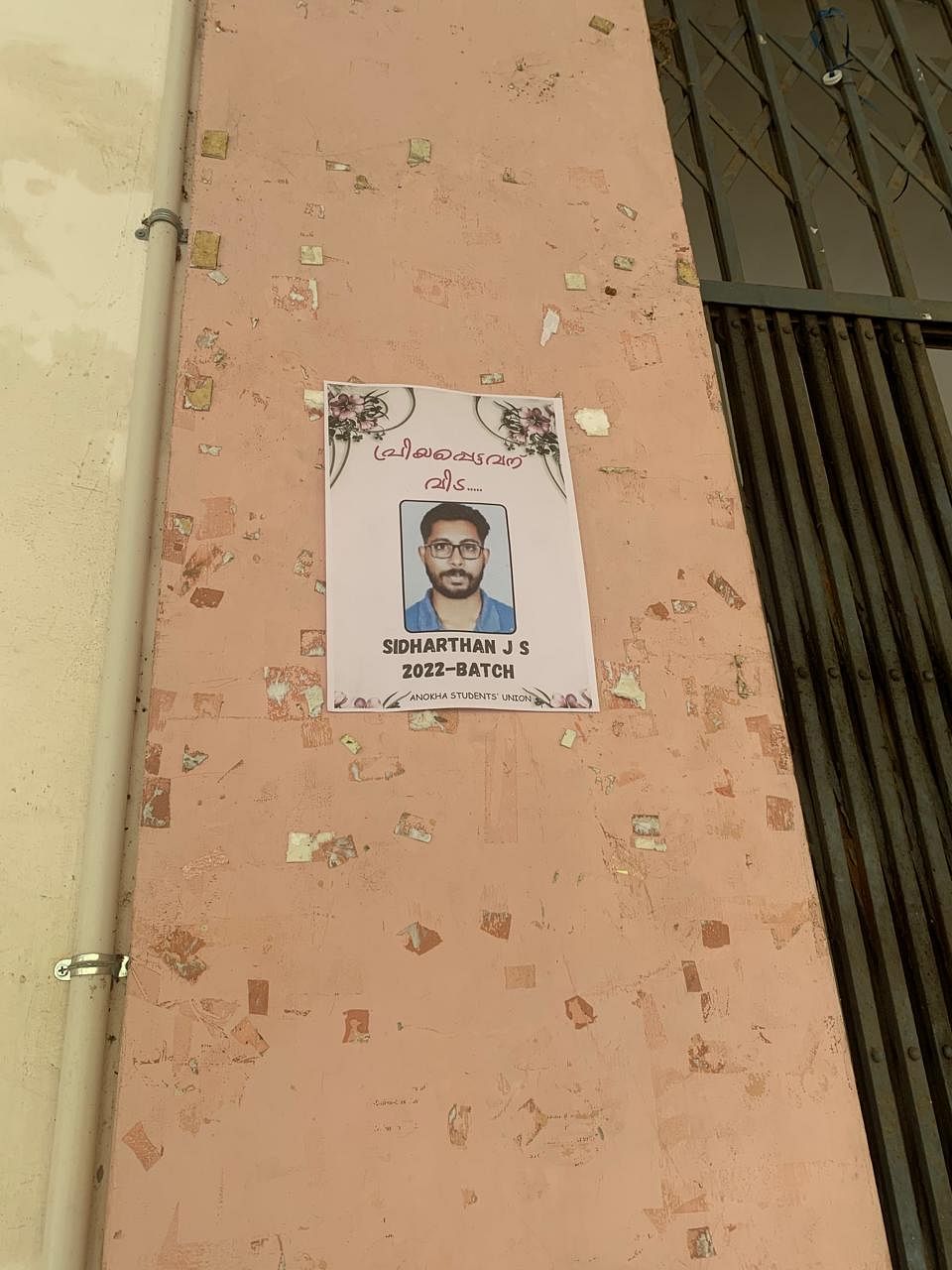

Not every college has Maharaja’s College’s fervour, even though a politically fraught environment ensures they’re often painted with the same brush. Kerala Veterinary and Animal Sciences University (KVASU), following the suicide and torture of JS Sidharthan, has been wrested into the spotlight.

Apart from showing death by hanging, the autopsy report in Sidharthan’s case showed “tramline contusions”–wounds from objects like canes, batons, wires.

Situated in the mountains of Wayanad, the terracotta buildings set against lush green hills, students and teachers at KVASU are reluctant to discuss his death. He has been memorialised by a non-descript sheet of paper stuck on the campus walls.

“Political parties have taken out protests and made it a big issue. But this wasn’t a political issue, it was a campus issue,” says a fourth-year B Voc student and an SFI member who did not want to be named.

After Sidharthan’s suicide, opposition parties took charge of the situation by holding protests and taking out marches. They say that the SFI is responsible for his death and that the beatings were carefully orchestrated by the party. SFI is the veterinary university’s singular political entity and is more self-contained—confining itself to dealing with campus issues.

“Of course, there were SFI students there. But the mob consisted of a number of other students as well,” says a student, an eyewitness to the incident. “I tried to get them to stop. I raised my voice and tried to call my seniors but I couldn’t be heard.”

Campus politics isn’t what shapes the contours of student life in KVASU. They are on their way to attaining a professional degree and are at differing levels of a strenuous five-year programme. They don’t necessarily have the time for politics.

“The processions were happening. But at the same time, at our clinics, animals were being treated. The good parts of our campus haven’t been shown by the media,” says a teacher.

Sidharthan, according to his peers, was a leader, a good student and an athlete. He was found hanging in the boys’ hostel. Security has since increased; a stern-faced guard with a handlebar moustache stands outside. A media circus ensued, and then a political one.

The campus was closed for five days. Students and teachers tried to keep above the water, but they were swept up by what was happening outside the gates. However, what bothers some the most is that Sidharthan’s death changed how their college is perceived.

“Everyone thinks we’re political now. A university of monsters,” says a student darkly.

If you are feeling suicidal or depressed, please call a helpline number in your state.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)

History is replete with events of bloodshed and violence in communist lands. Communism must be banned. British did the right thing by banning communist literature in colonial India, but we Indians failed by embracing communism-socialism duo.