Hyderabad: Restless children squirm through the morning roll call at an Old Hyderabad school. But the familiar chant of “present, teacher; absent, teacher” is gone, as is the dusty attendance register. Instead, a sleek Samsung tablet is held up in front of them. Facial recognition software logs their presence, the teacher presses a button, and an algorithm does the rest.

This is all part of Telangana’s latest technological push. Facial recognition technology (FRT) is now being used to confirm schoolchildren’s attendance, pay pensions, renew driving licences, crack down on crime, and even for e-voting. But smart tech doesn’t always mean fast tech — or efficiency.

In the classroom, a harried teacher goes from child to child, clicking each student’s photo on her tablet. She has to wait for each photo to buffer and process, before a green tick gives the all-clear to move on. Then, she must fire off a message on the school cluster’s WhatsApp group while the attendance app uploads the data. Only then can lessons begin.

Telangana’s choice of FRT over biometrics was influenced by the potential spread of coronavirus through fingerprints. It was the state’s “apda mein avsar” moment, to use Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s exhortation to transform the Covid disaster into an opportunity.

Now, it’s becoming a standard despite concerns about privacy and data breaches. And Hyderabad is the poster child for this high-tech governance.

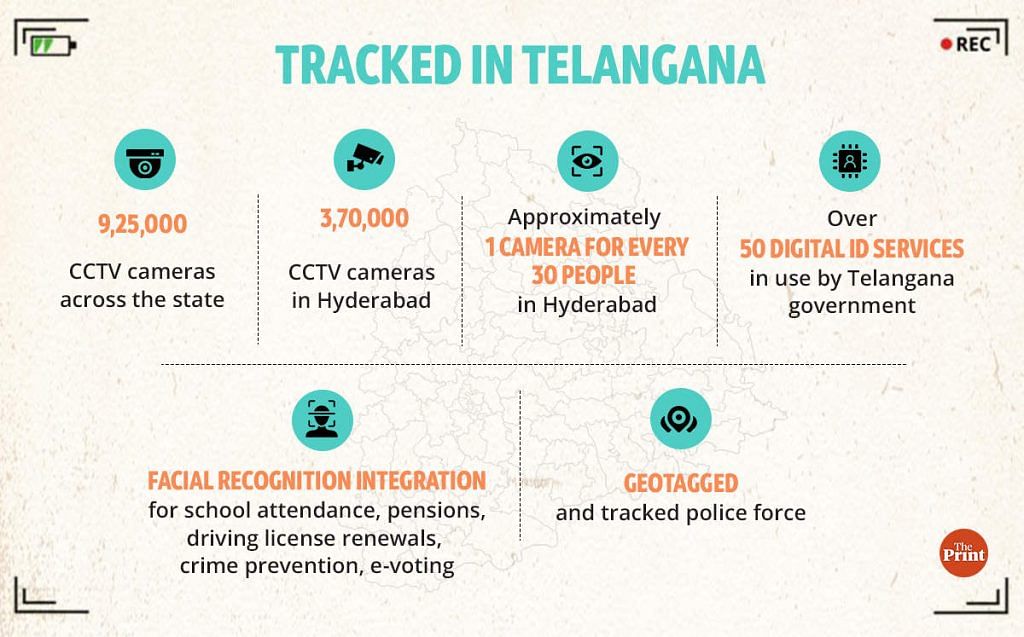

CCTV cameras perch alongside crows and pigeons on the city’s power lines. From traffic signals to temples, mosques to malls, gated colonies to government schools—cameras are ubiquitous. There are around 925,000 cameras across Telangana (including private installations), of which 370,000 are in Hyderabad alone. A rough calculation puts the ratio at one camera for every 30 people in the city. And a colossal new command-and-control centre, with four 20-storey blocks, keeps 24×7 tabs.

What began as an aspirational Cyberabad in the 1990s is today the surveillanceabad of southern India. The overarching goal is to forge smart cities of the future—with gleaming interfaces, endless eyes, and invincible security grids, reminiscent of Netflix’s Black Mirror.

While some say it’s improved transparency in government services, others are more cautious. People are aware they’re being watched—and that surveillance doesn’t always mean safety.

The way people behave across the city is also changing—some have begun to avoid praying at Mecca Masjid because of the sheer number of cameras dotted around and inside the premises, while others are more confident while navigating the city. Hyderabadi children across classes and religions are growing up in an environment where constant digital monitoring is the norm.

“Everyone says Hyderabad is a panopticon,” said Srinivas Kodali, researcher and cybersecurity expert, evoking the image of a prison layout where guards can watch inmates, but not vice versa.

“It’s society that’s created this panopticon—it doesn’t exist in isolation. The problem is that society doesn’t understand exactly how we’re being watched, and with what gaze.”

– Srinivas Kodali, researcher and cybersecurity expert

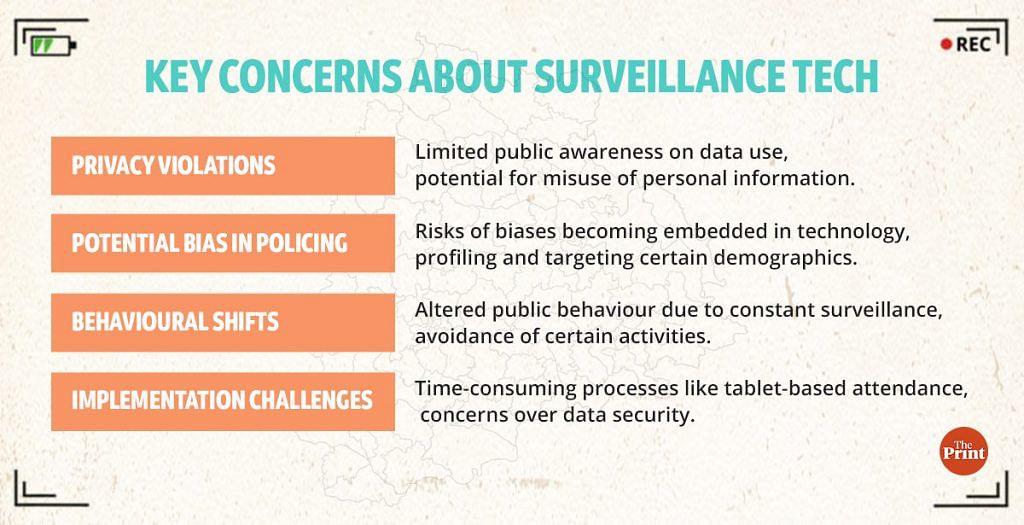

There seems to be general consensus among Hyderabad’s public about the importance of FRT in reducing crime and appreciation for the high-tech way Telangana uses it. But there’s not much understanding around data privacy concerns, or how FRT can be misused to unfairly target marginalised groups.

“We need technology, and digital services do improve our day-to-day lives,” said activist SQ Masood. “But everyone’s sociopolitical contexts are different. Technology is a tool, not a solution.”

Under constant watch, women are more confident in public spaces and the elite feel more secure.

But Muslim men are walking on eggshells to avoid the ‘suspicious’ label, and young couples are searching desperately for hidden corners to steal a touch.

Also Read: Hadiya isn’t missing as her father claims. She’s just moved and wants to be left alone

The blink of an eye

Hyderabad, the city of pearls is fast becoming the city of paranoia. Sanya, 17, is nervous. She has just bunked school for a date with her boyfriend in the bazaar near the city’s iconic Charminar and is anxiously awaiting his instructions about their meeting spot. Couples—especially young men—are more aware of the CCTVs around them, she says, and her boyfriend is particularly paranoid. He doesn’t want to be caught at the wrong place at the wrong time.

“Earlier, it used to be people who might know our parents. Now, it’s these cameras,” she said, looking around and pointing to those she can see. “I think they’re very good because crime has come down, and now people know they’ll be caught if they steal. But I also think people are more scared in general. But it depends on whether you have something to be scared about.”

Part of the paranoia has to do with the fact that her boyfriend recently received a traffic challan for not wearing a helmet. He was photographed by a police officer using the state’s high-tech policing app, TSCOP, and FRT was used to check whether he had any other crimes against his name. He didn’t, but he’s heard rumours of others who’ve been picked up for petty crimes they didn’t know they had committed. Best to be safe, says Sanya.

Moral policing has taken on a new dimension in public spaces in Hyderabad with cameras. And people are censoring themselves more. It’s not illegal to hang out with a romantic partner, but the fear of being recorded has seeped into Sanya’s boyfriend’s psyche.

FRT is being implemented by different agencies across the state in different ways. We’re using it to improve our internal efficiency

-Jayesh Ranjan, principal secretary for IT

“These cameras are a good thing,” said Mohammad Faiyaz, 34, who runs a mobile repair shop down the street from Mecca Masjid. “Yes, people are afraid to get traffic challans in general, but the reduction in crime is definitely a good thing.”

However, he knows regulars who have stopped coming to Mecca Masjid because of the heavily surveillance in the area. He claims it’s because they’ve all had run-ins with the law, and would rather not risk being rounded up for anything just in case they’re identified using FRT.

Petty crimes mount against someone’s criminal profile, which gets created the moment a policeman uses FRT on them on the TSCOP app. And if a person caught on FRT for a minor offence also shows up on a criminal database, it may immediately change how they are perceived and treated.

“I think everybody is more aware of the fact that at any moment, any action they’re doing in a public space is being recorded,” said lawyer and policy researcher Anushka Jain, who has worked on Project Panoptic, run by the Internet Freedom Foundation (IFF). IFF has also worked with Amnesty International on their Ban the Scan project in Hyderabad.

According to Jain, people aren’t just worried about the legality of their actions, but also about whether those in power perceive them “negatively”. Protests are a case in point—people have now begun to wear masks to demonstrations to avoid being captured by cameras.

The integrated command-and-control centre of the Telangana Police has access to every single camera in Telangana. Nothing goes unrecorded, or unnoticed.

‘Safest city of India’

At the other end of the city, elite Jubilee Hills is where the city’s wealthier youngsters come to party.

Here, the wide roads and busy traffic junctions are continuously surveilled by CCTV cameras to target common offences like drunken driving. And they’ve come in handy to crack serious crimes too. A high-profile gang rape case in 2022 was solved using footage from over 150 CCTV cameras in Jubilee Hills, according to a police source.

Now, everyone wants a piece of the high-tech security action. Private offices, gated communities, and various clubs across Jubilee Hills are using FRT linked to turnstile gates for automatic entry.

“Public safety and the safety of women in public spaces is a big issue in India, and there’s political will and money behind finding a solution,” said Jain. “So, there’s a lot of interest in creating safe cities and smart cities, to ensure public spaces are safer. And one way in which the government is doing that is through CCTVs and facial recognition.”

Not far from Jubilee Hills stands the city’s new Command and Control Centre (CCC), inaugurated in August 2022. In the heart of Banjara Hills, it can be easily confused with a corporate office. Described as the city’s “third eye” by former Hyderabad police commissioner CV Anand, the CCC has access to every single camera in Telangana. Nothing goes unrecorded, or unnoticed.

“Safest city of India — IT Hub — Safest — Greenest,” declares a massive board in the reception area of CCC’s first tower.

The police are tech-savvy too, relying heavily on digital tools to fight crime. The most celebrated medium is the award-winning TSCOP app, which has single-handedly changed policing in Telangana.

An SHO at a police station in Old City pointed out all the ways in which TSCOP has made policing easier and more streamlined—conducting FRT, cross-checking with the CCTNS (Crime and Criminal Tracking Network and Systems), pulling up history sheets, and guiding officers on the next steps when someone is apprehended.

The officers themselves are geotagged and tracked, allowing TSCOP and other apps to monitor response time from the moment a report is made to the arrival at the crime scene.

However, reliance on technology for policing is not without criticism.

For one, there are no laws to directly regulate FRT and biometrics. The other issue pointed out by critics is that technology takes human interaction out of the equation. Being connected to communities and having informants is a big part of policing, and moving everything to surveillance infra and apps like TSCOP turns the police into near “cyborgs,” according to Kodali.

“In relying entirely on technology, not only is the system becoming invisible to the citizens, it’s becoming invisible to the people inside the system,” he said. “People don’t know how detrimental this can be, and neither does the policeman doing his job.”

In the routine of everyone just doing their job, the darker repercussions are barely even considered. “What happens when you implement the law perfectly on only (a) part of the population?” asked Kodali.

When FRT overlaps with police bias

Telangana’s recently elected Congress government is keen on enhancing its technological prowess.

Shortly after the swearing-in ceremony on 14 December, IT & Industries Minister Duddilla Sridhar Babu mandated that all government departments and agencies leverage digital technologies to enhance public service delivery and efficiency. The city’s new police commissioner, Kothakota Sreenivasa Reddy, took charge on the same day and also committed to using the latest technology.

But, for numerous residents, technology has played a role in sidelining them, blocking their access to essential services.

For instance, many in Telangana have faced trouble receiving their passport because of ‘cases’ booked against them under the Epidemic Diseases Act for violating lockdown norms during the height of the Covid pandemic. Around 40 people reportedly didn’t receive police clearance in Telangana’s Adilabad alone. Beyond passports, residents struggle to secure bank loans, even though these cases aren’t criminal. Moreover, minor offences, such as public smoking or traffic violations like failure to fasten a helmet strap, have left many people with a blemished record.

Activist Masood has filed a PIL challenging the deployment of FRT, prompting the Telangana High Court to issue a notice to the erstwhile BRS government. In Masood’s case, he was stopped by the police in May 2021 while returning home from work for violating lockdown rules. The police insisted that he remove his mask so that they could take his photograph and use FRT—this, ironically, was another violation of lockdown rules, especially at the height of the second wave of Covid.

The incident was a turning point for Masood. He stopped praying at Mecca Masjid, and has also stopped volunteering near Charminar during events like the Ganesh Chaturthi processions.

The government wants to eliminate middlemen and prevent leakages, and technology is the only way to do that

-Sidharth Kukatlapalli, founder of Hyderabad-based startup Syntizen

The fear of being in the wrong place at the wrong time has affected normal patterns of behaviour in areas like in Hyderabad’s Old City.

While this may suggest heightened vigilance in policing, critics argue that certain sections of the population—especially marginalised groups—may be unfairly targeted.

Existing police biases towards ‘suspicious looking people’ are now being codified into technology, raising concerns over both privacy and profiling.

‘Operation Chabutra’, a police-led initiative that rounds up youngsters found loitering in the city late at night without ‘valid’ reason, exemplifies this issue. These men are temporarily detained, their photos taken, and FRT applied. If no criminal history is found, they receive counselling from the police. This practice, part of the police’s “proactive approach” to prevent “rowdy” behaviour, has been intermittently conducted since 2015.

“This is to satisfy the elite majority of the city, to give them the impression that police work is being done,” said Masood. “But when a crime happens, the pressure on the police can make them target certain communities.” He pointed out that cordon-and-search operations tend to be conducted civilly in affluent areas, but border on harassment in low-income and Muslim areas.

Minor offences, such as public smoking or traffic violations like failure to fasten a helmet strap, have left many people with a blemished record.

‘Right services to right citizens’

Everyone agrees on the importance of technology in governance: it has the potential to cut through the proverbial red tape, remove the middleman, and take welfare delivery straight to the citizen.

That’s exactly what the rationale is for Telangana.

“FRT is being implemented by different agencies across the state in different ways,” said principal secretary for IT Jayesh Ranjan. “We’re using it to improve our internal efficiency.”

One such case is Telangana’s Pensioner Life Certificate through selfie programme, introduced in 2017. Of the state’s 2.5 lakh pensioners, 1.3 lakh are now registered through the scheme and receive their pensions through FRT. The technology can detect whether the selfie is a live image or a photograph of a photograph, and is also able to detect aging. It has a reported 98 per cent accuracy rate, according to Ranjan.

I don’t think we’ve considered the long-term impact of this on children, and how they’ll adjust to being constantly surveilled—or what this does to parents

-Prateek Waghre, executive director of the Internet Freedom Foundation

Another example is the renewal of driving licences, a project launched in 2019, and the “Dost” project, which offers college counselling to recent graduates of grades 10 and 12. And in a truly pathbreaking first, FRT was used for e-voting in 2021 in a dry run with around 3000 people in Khammam district.

Other states are interested in following Telangana’s lead, impressed with the way technology is being integrated into government services. Tamil Nadu’s IT Minister Palanivel Thiagarajan took a team to visit Hyderabad earlier this year to learn more, and Odisha and Bihar have indicated interest in the e-voting dry run.

“The fact that FRT is being adopted by the state itself is a big thing,” said Sidharth Kukatlapalli, founder of Hyderabad-based startup Syntizen, which was founded at the government-based incubator THub. “The government wants to eliminate middlemen and prevent leakages, and technology is the only way to do that.”

An identity solutions company, Syntizen has integrated over 50 digital identification services currently being used by the Telangana government. “We’re empowering m-governance (mobile governance) with the advancement of technology,” said Kukatlapalli. “The Telangana government wants to bring transparency into the system, and make sure the right service reaches the right citizen.”

Kukatlapalli underscores the government’s dedication to data security. His firm hosts these solutions on the state’s data centre rather than on a cloud—which means the government owns this data. Another non-negotiable security measure is an annual computer emergency response team (CERT) empanelled audit to prevent data leakages. Additionally, blockchain technology is employed to secure encrypted votes, which are cast during electronic voting.

Also Read: ‘Har Ghar Camera’— In Gorakhpur village, 103 CCTVs crack down on crime & romance

The invisible watchers

While the government may be dedicated to security, the fact that it owns this data raises other kinds of security concerns.

This information in the wrong hands—or government—could lead to detrimental consequences on society, according to both Kodali and Masood.

“Our attempt in Telangana is to ensure that we are paperless, contactless, presence-less, and accessible anytime, anywhere,” said Ranjan, citing the example of Estonia as a blueprint for Telangana.

But this goal seems to be running into issues, like in the case of marking attendance for children in government schools.

A member of the state’s teachers union said that government schools in the state already lack both infrastructure and staff, and the introduction of FRT has been more cumbersome than convenient. It’s quicker to mark attendance manually since servers often take time to buffer and upload data. Parents have also raised concerns over their children, especially girls, being photographed.

“Biometrics made sense, but why the face? We need more money to improve other facilities, we didn’t need this Rs 30,000 tablet,” said a teacher at an Urdu-medium school who has to photograph around 100 children every day.

The process has become a hassle for already overworked teachers, but there’s no sidestepping it—schools have been issued notices for not complying with marking FRT attendance.

The children, meanwhile, are voiceless. “I don’t think we’ve considered the long-term impact of this on children, and how they’ll adjust to being constantly surveilled—or what this does to parents,” said Prateek Waghre, executive director of the Internet Freedom Foundation.

This “technosolutionist” mindset is taking over the country, he added, and there’s a worrying lack of clarity on how automated systems are being used to make decisions that affect lives. “It’s cliched to use the panopticon example, but that’s what it is. We need more transparency about how these systems are being used. There is increasing deployment, and we won’t be able to arrest that trend—but it is still important to think about how these systems are being designed, and why there isn’t more transparency from the state.”

Essentially, the real question is: who is watching the watchmen?

(Edited by Asavari Singh)