Ajmer: At the end of a long, quiet, car-lined alley of a middle-class neighbourhood in a Rajasthan city, is a house with no name and number. Nothing about it stands out but in last 18 years, policemen in uniforms and plainclothes have visited this house at least seven times. They came looking for a woman who doesn’t want the past to catch up with her.

Every time the doorbell rings, she peeps from the balcony. Her son opens the door to say: no woman by this name lives here—a standard response for years.

The police visits are part of a three-decade-old case: the 1992 Ajmer blackmail and rape scandal. In the early years of 1990s, powerful men from politically connected families in Ajmer gangraped, video-taped, photographed and silenced multiple schoolgirls and college-going women—16 teenagers as per official records—for months. It was a scandal that captured the city’s imagination for years, spawned countless headlines and fuelled a Congress vs BJP tit-for-tat. But the women didn’t get justice.

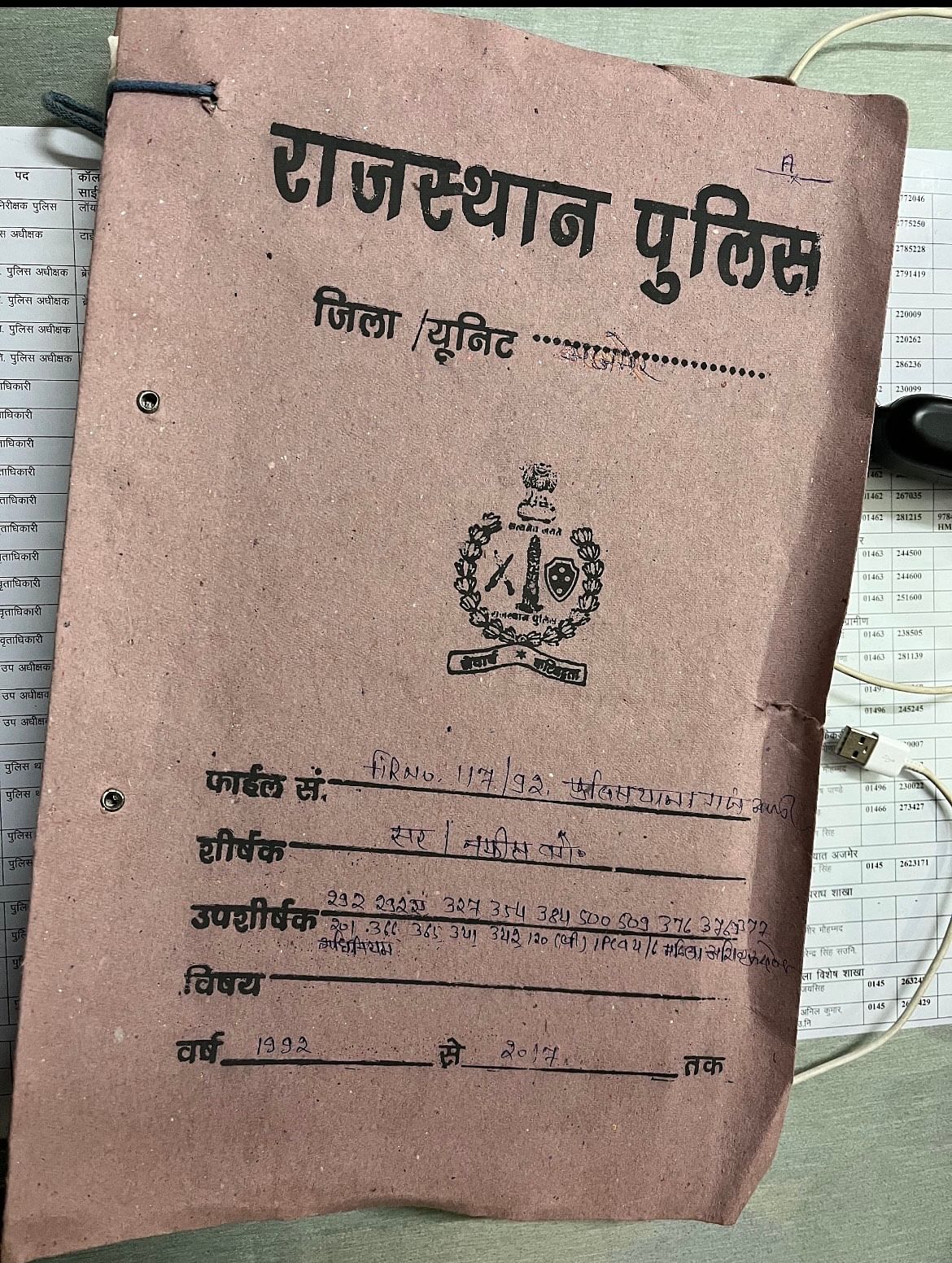

Among the 18 accused were the Chishti duo, Farooq and Nafis, who belonged to the extended Khadim family associated with the Ajmer Sharif Dargah and held key positions in the Congress. Both men continue to wield influence in Ajmer—Farooq was convicted but his sentence was commuted and he was released in 2013. Nafis is out on bail.

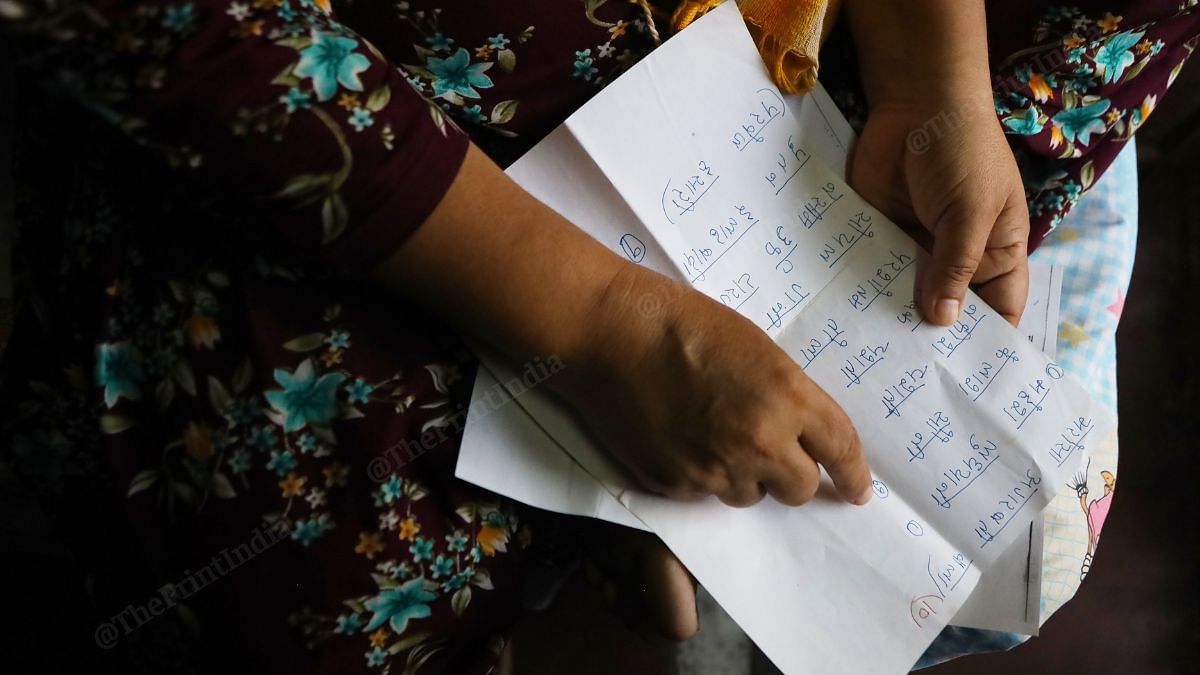

Most survivors turned hostile, but one woman stood by her truth. She made the most powerful, wrenching testimony against her nine rapists. She gave her deposition in court, not once but thrice. Her statements led to many convictions. Though she is key to the trial, she has now had enough.

“Let her move on. She has gone through a lot,” the woman of the house said, deliberately speaking in third person to avoid being identified. She came down from the top floor, her voice was firm but her hands shook as she held a tea cup.

But Netflix and Bollywood have smelled a story in her beleaguered life, its trials and tribulations now. Social media chatter, WhatsApp forwards and YouTube videos are tapping at the survivors’ heels too. Her hard-fought privacy and anonymity, like many others in the gangrape case, will possibly get more brittle.

On 14 July 2023, a new movie called Ajmer 92 directed by Pushpendra Singh and produced by Umesh Kumar Tiwari will be released in theatres. Another film and music production company, Tips, has just bought the rights from a crime reporter in Ajmer for a movie called Ajmer Files, to be directed by Abhishek Dudhaiya. Both projects were tweeted by Bollywood business analyst Taran Adarsh.

In the months ahead of Rajasthan assembly elections and in the season of movies like Kashmir Files (2022) and The Kerala Story (2023), more and more real life incidents are being dramatised and blown up for politically partisan goals. Many fear that the Ajmer case—in which the rapists were predominantly young Muslim men and the women were mostly Hindus—will be exploited for polarisation. But amid all this limelight, the real price will be paid by the survivors who have carefully meandered their life for over three decades now.

The film and web series have resurrected the Ajmer sex scandal, putting it back in the public gaze. It’s playing out in debates on national television channels where activists, feminists and prominent citizens vent their outrage while Congress and BJP members fling accusations at each other. Behind the scenes, the powerful Khadim family of the Dargah is lobbying against their release, said a source from the Anjuman Committee, the Dargah’s governing body.

“A girl is such a thing that can corrupt anyone,” said Khadim Sarwar Chishti, who is the secretary of the Ajmer Sharif Dargah, Anjuman Committee, to a journalist in a clip that has since gone viral.

“This has become a communal issue and the Muslim community should not be hounded by the actions of a few individuals,” said a member of the Dargah on condition of anonymity.

“The case has come a long way. It was never about justice, and it is not about justice this time either but it always remained a political sex scandal for popular consumption. As the TV screen flashes headlines again, I am reminded of the school and college girls who we saw every morning on the roads,” Beena Sharma, a retired Hindi professor from Savitri college said. “At the peak of the case, our principal had arranged the photos for the staff of 60 lecturers and professors, to identify the victims. We couldn’t trace them in the classrooms.” she added.

Also read: Gangraped in teens, visiting courts as grandmothers: 1992 Ajmer horror is an open wound

Nightmare continues

As the salacious coverage of the scandal grew over 30 years, the elbow room for women’s quest for new lives shrank. They grew more and more estranged from the case.

“Ninety percent of my life is gone. What will I do with 10 per cent justice,” said Sushma*, the first survivor identified by a local journalist after her naked photos were published in local newspapers when the scandal broke. Unlike many others girls in the case, she came from a poor family and lacked the agency to stonewall journalists looking for the next scoop.

Now, a June 2023 interview with a local television journalist has upended her life again. Though her face was hidden in the shadows, her voice was not altered as she recounted the rapes and blackmail while mourning the death of her brother. And suddenly people were asking her family if she was one of “those girls”.

Her other brother tried to jump from a roof.

“He asked me, who will marry my daughters?” said Sushma, “At least 20 people have asked him if I am the woman in the video.” He ranted and raved at her for unlocking a cupboard full of skeletons he would rather forget.

Sushma, who felt betrayed by the journalist, made frantic calls to his editors in New Delhi to get the video removed from their YouTube channel.

“It was my brother’s terahvi [13th day last rite ritual] and I was in grief. You shoved a camera on my face. I trusted you because you said you also have behen-beti (sisters and daughters),” she shouted at them on the phone.

But now, she has seen news about a new movie, new OTT series, and YouTube videos on her WhatsApp. Her nightmare continues.

“Will they show my face in the movie? They are publishing my nude photos which I saw in court,” she asked her best friend anxiously over the phone.

The 30-year chase

Between ever-growing hungry crime reporters and policemen on-the-chase, the case became a hot-button issue for years. New revelations were promised every few months by the local media. And the policemen were looking for survivors and complainants who didn’t want to be found anymore.

They made a breakthrough when they tracked down Krishnabala*—the woman whose testimony got the convictions. But the scandal broke months after her father was transferred to another city in Rajasthan. For Krishnabala, it was a fresh start away from her abusers—and Ajmer. She tried piecing together the jagged pieces of her life. She had a B.Sc. degree from an Ajmer college and she chose to do another bachelor in fine arts in the new city.

She wanted to start afresh, reinvent her life, ambitions and story. But then, the police knocked on her door. They knew she would avoid them. So, they had a plan.

“We pretended to be from her [old] college and asked her to accompany us to Ajmer for marksheet purposes,” said Dharmendra Yadav, a retired police officer who was part of the CID crime branch team headed by then superintendent of police, NK Patni. Yadav and additional superintendent of police Janardan Sharma played a crucial role in investigating and preparing the first chargesheet in the case.

The two men showed her the photographs they had recovered in which she was naked. Krishnabala understood that they were trying to hide the case from her parents. But there was no escaping the past and she agreed to help them.

The crime branch team’s biggest challenge was to trace the young women, and interrogate them while keeping their parents in the dark. It was a tricky, tightrope walk between pursuing justice and respecting the women’s need for privacy and autonomy.

“[In 1992] The city was boiling. There were already a few instances of young girls dying by suicide. The case became high profile and yet so sensitive. The girls needed privacy and protection both. We couldn’t take them to any government office, police station or even court,” said Yadav, who stayed in Ajmer along with Sharma for six months during the investigation.

The first survivor they identified was Sushma through the photographs splashed out on front pages of newspapers and tabloids. Yadav recalled the relief he felt when he spotted her in the lanes around the Ajmer Sharif Dargah.

“When we started talking to her, she ran away. We ran after her for a kilometre. Finally, she agreed to come with us and tell us everything,” he added. Then the police identified Gita* who led them to Krishnabala who led them to Raanu* who led them to another girl and another and another. Many of them were from Sophia Senior Secondary School and Savitri Girls’ College.

“We were able to trace 30-35 girls. But only 16 came to record their statements. But most of them turned hostile,” Yadav added.

Krishnabala’s last visit to a court was in 2005, barely five years after she got married. In 2018, another accused, Suhail Ghani Chishti surrendered at an Ajmer court after 26 years on the run. The police turned to Krishnabala.

“We tried to contact her through her sister’s husband, but he told us that after the 2005 court visit, Krishnabala had tried to self-harm. We couldn’t deliver the summons to her given her mental health,” said an SHO who escorted dozens of witnesses to court between 2020-2021 for the trial of Suhail.

Today at 51, Krishnabala is a mother. She guards her privacy fiercely. She is done serving the cause of justice.

“Why do we have to call them again when they have already testified multiple times?” asked the SHO.

This was an important question. The effort began to convince the court to proceed on the basis of earlier testimonies and not seek fresh ones.

Last year, the current prosecution lawyer Virender Rathod had submitted an application in the POCSO court requesting it to consider the recorded statements of Krishnabala and two other survivors for the ongoing trial of the six-remaining accused in the case.

“It is the accused who have delayed the trial by either absconding or not appearing before the court. They have been summoned to the court many times since 2004. This has inflicted immense pain, and led to many of them [survivors] committing suicide attempts,” the application reads.

The sitting judge Ranjan Singh is yet to decide on the application.

Also read: Rajasthan is stormed by caste mahasabhas. Then a ‘berozgar’ group said enough

Modus op·er·andi

A B.Sc. student in Savitri Girls’ College, Krishnabala used to walk to college from her family’s rented home in Civil Lines, where they lived between 1987 and 1991. That’s when she met Gita, another student from Savitri Girls Sr. Secondary School. The two became like soul sisters. But Krishnabala was unaware of the danger lurking beneath the close girl-bonding.

“I started treating Gita as my younger sister. She often visited my house, and my parents started trusting her as well,” Krishnabala’s testimony in court read. What she didn’t know was that Gita was being manipulated by a gang of young men led by Farooq and Nafis. She was already trapped in the cycle of blackmail and rape. Her task was to bring more women to the gang or risk having her secret photographs out in public.

“She used to say that she has five Muslim brothers, who are so nice,” said Krishnabala in her 2005 testimony.

Then there was a party invite that sounded harmless at first.

When the car reached a poultry farm in Hatundi on the outskirts of Ajmer, Nafis and another key member of the gang, Ishrat Ali, were already there. She said Ali raped her that day.

Krishnabala was dropped back home at 5 pm with a warning from Ishrat: “I will defame you if you tell this to anyone. Whenever you are called for, you have to come, otherwise I can do this to your sister too.”

She came home and washed her blood-soaked clothes.

Then the relentless blackmailing began. She was called again and again with the threat that she would be exposed. She was called to Farooq’s bungalow at Foy Sagar Road in Ajmer where four men raped her—Nafis Chishti, Anwar Chishti, Salim Chishti and Ishrat Ali.

They just wouldn’t let her be. They kept meeting her outside school, in the marketplace, at friends’ hangouts and pressuring her.

Over the next eight months, a mob of men gang-raped her 25 times.

“Once Farooq raped me and asked me to please his boss Almas Maharaj, who had come from US,” she said in her statement. Krishnabala told the court that she felt so powerless that she wasn’t even able to confide in anyone in her small, conservative town.

In 1998, right before the case that Yadav and the CID team had built was set to go to trial in the sessions court, Farooq and Nafis allegedly tracked her down in the new city. They threatened her family and forced her to file an affidavit refusing to identify them. That didn’t sit well with her. For years, it haunted her.

In her 2005 testimony, she corrected that hostile affidavit, “Once I became fearless, I spoke the truth.”

Also read: Surat’s diamond industry has a suicide problem. Police to bosses, nobody wants to join the dots

Fodder for the dailies

Eighteen men were accused, but only eight were convicted by the sessions court in Ajmer. Of the eight, four were acquitted by the Rajasthan High Court on 20 July 2001. The Supreme Court on 19 December 2003 commuted the sentences of the other four convicts—Moijullah alias Puttan, Ishrat Ali, Anwar Chishty and Shamshuddin alias Meradona—to 10 years.

Farooq claimed he was mentally incompetent to stand trial but in 2007, a fast-track court sentenced him to life. In 2013, the Rajasthan High Court deemed he had served enough time and released him. Nafis is one of the six remaining accused who are still facing trial. Almas Maharaj is still absconding, and there is a lookout notice for him.

In Ajmer, the case brought out the investigative journalist in citizens. It was as if everyone, from librarians to property dealers, started ‘digging’ for the truth, claiming to have inside or exclusive information. Everybody passed conjectures as truth. There are so many versions of the story that it is now becoming hard to separate truth from hearsay. It provided enough fodder to fuel an existing news media cottage industry.

Back in the 1990s, there were 150 ‘news’ publications and 350 ‘journalists’ in Ajmer, according to an India Today report by Vijay Kranti. More new newspapers sprouted with the gang rape scandal as their singular business model.

It was the next big thing for small shopkeepers, junk deals and housewives who were already specialising in advertisement revenue collection, blackmailing, extortion, mud-slinging and touting favours, dominated the list of accredited journalists at the local public relation office. Today, the business has shifted online with conspiracies masquerading as truth on YouTube.

But for many journalists, it was also a moment of heroism. Dainik Navjyoti reporter Santosh Gupta broke the story on 21 April 1992, but it did not drum up the outrage he was expecting.

“My reporter came to me frustratingly in 1992. He told me, ‘Sir, nobody’s blood is boiling after my expose on the blackmail scandal published,” Deenbandhu Chaudhary, editor in chief of Dainik Navjyoti recalled. Gupta later told ThePrint that Chaudhary’s version is exaggerated.

Chaudhary asked the reporter to show him the photographs. “I had never seen such horrific acts in my life. I took a call to publish the nude photos on the front pages the next day,” said Chaudhary.

The first nude photographs the paper published were of Sushma and two gang members Kailash Soni and Parvez Ansari. They decided to leave the faces visible, but masked Sushma’s eyes with two black strips.

“If we had hidden her body, then there would have been no public outrage,” Chaudhary called it a bold decision. He proudly talks of a profile on him by a national magazine. But for Sushma it was yet another violation of her body.

“I felt my dignity was snatched away,” she said.

Some local dailies used the photos to extort money from the accused. Others cashed in on the fear and suspicion and targeted parents of children and teenage girls.

“As soon as a wedding card was printed, an extortion call would come with a standard line—We will publish your daughter’s name,” recalled Santosh Gupta, who has now left journalism and works at a hospital.

After Dainik Navjyoti, Madan Singh, then 32, a criminal and extortionist with a police record entered the fray. He, too, had been running a local weekly titled Lehron ki Barkha, which he converted into a daily at the peak of the gang rape story.

Sensational headlines with no ties to truth were his speciality: ‘Abhiyukton ka mahila ke sath ashleel mudra mein nachte hue photo’ (Photo of three accused and one woman in a vulgar dance position); ‘Deh Soshan ke baad garbhpat ki goliyan khilate the’ (After sexual exploitation, girls were given abortion pills). He claimed that the then Chief Minister Bhairon Singh Shekhawat didn’t take action because BJP leaders were also involved in the gang, that the girls were bribed lakhs to turn hostile. Yet another daily ‘reported’ that two BJP leaders who sexually exploited the girls were trying to incite communal riots to save themselves.

His coverage turned the gang rapes into a political sex scandal. He alleged that former Congress MLA Rajkumar Jaipal, along with another party member Lalit Jadwal and Sawai Singh (ex-municipal councillor) were sexually abusing girls.

Within months, Singh had succeeded in angering a swathe of Ajmer from fellow criminals to politicians.

Around 10 pm on 4 September 1992, he was shot by two men in a Maruti van while he was on his scooter. One of the bullets hit his right hip and injured him seriously. He jumped into a drain and somehow managed to escape. He was admitted to Jawaharlal Nehru Hospital where he thought he was safe. The following day, in its 76th report on the case, Lehron ki Barkha ran a story claiming that a former MLA and another leader were conspiring to kill Madan Singh.

On 12 September, men armed with pistols barged into the hospital room and pumped five bullets into him. His mother, Ghisi Kanwar, was sitting next to his bed. She held one of the accused’s legs and let go only when he hit her on the head with his pistol. This was the testimony she gave in court, before she turned hostile. Singh died two days later.

Jaipal, the ex-councillor Sawai Singh and three others were arrested for murder but they were acquitted after eyewitnesses turned hostile. In January this year, Madan Singh’s two sons killed Sawai Singh in a resort in Ajmer.

“We took revenge,” his son Surya Pratap shouted at the crowd gathered at the resort. Both men were arrested for murder.

Also read: Young women are jumping into wells in Barmer. It’s a suicide epidemic

Always under scrutiny

Ajmer isn’t the only city to bear the burden of rape and blackmail case. In July 1994, Jalgaon in Maharashtra was rocked by a similar case where a nexus of local politicians, lawyer, doctor and government officials drugged, raped, and trafficked women—many of them were school girls.

The accused used to lurk around schools, colleges, beauty parlours, and bus stands, looking for potential victims. The girls were later photographed and blackmailed. The case followed the similar trajectory as Ajmer rape case where the FIR was delayed, witnesses turned hostile and weak evidences. The ‘Jalgaon sex scandal’ resonated in the streets of Ajmer.

Both the cases alarmed parents, schools, college authorities and neighbourhoods. Young women everywhere paid the price. Their movements were restricted and every action scrutinised.

“Lives of a whole generation of young girls revolve around these two cases,” said Indira Pancholi, a social activist who had started the Mahila Samuh Ajmer in the late 1980s.

Pancholi and a group of young women wanted to create a safe space for gender justice and female rights in Ajmer. Many young women from Sophia and Savitri colleges joined their workshops in their office.

“We had a group of 6-7 [girls] from one of these schools. We felt that they wanted to convey something, but then the case blew up. The girls stopped coming,” Pancholi said. Her group then started connecting dots between two suicide cases of young girls in the past to what was going on in Ajmer at the time.

“One of the girls lived close by. She was a daughter of an RAS [Rajasthan Administrative Service officer]. The other hanged herself after some time. Her father was a doctor,” Pancholi said that the girls who visited her group were curious and bright.

Sophia College and Savitri School were never named by the police. Even though, retired policemen say, they were discreet when they looked for the survivors, they came under intense scrutiny by the media.

For a few months, worried parents showed up to check the attendance of their daughters to reassure themselves that they were ‘safe’ in classrooms. Schools tightened attendance rules so that girls couldn’t sneak out.

“We were hurt, raged and in pain,” said Sister Pearl, the current principal of Sophia Girls’ College. She was a class 12 student in Sophia School in 1992. She said the matter was hushed. “We never knew who the victims were. It could have been anyone.” But she remembers being told to not go outside and her parents had become extra cautious.

She still feels rage every time she comes across a YouTube video “spreading” lies about Sophia School. Some reports claim that as many as 250 girls had been victimised by the gang.

“They are stigmatising the institution by spreading false narratives so girls drop out of Sophia,” she said. However, Sophia’s class 11 and 12 admissions in 1992 and afterwards show an increase in enrolment, as per the official records. Savitri School too didn’t see a decline in enrolments. But for years, the girls were watched all the time. The school no longer runs its boarding facility.

Pancholi and other members of her group kept hearing something or other about the case during their field visits in villages.

“People would often blame the girls and say, ‘This is why we shouldn’t send them away to hostels,” she said.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)