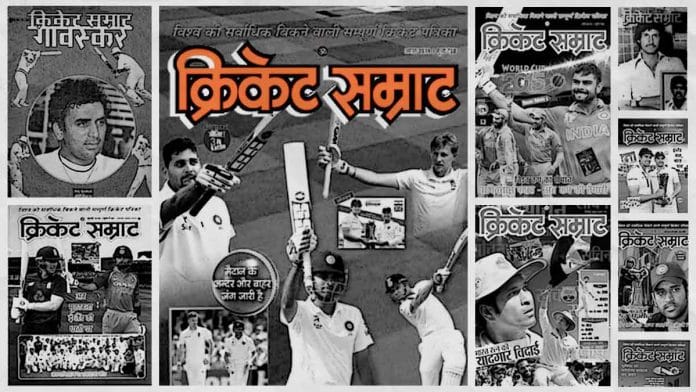

That the Covid-19 pandemic and lockdown would wreak havoc upon the Indian media industry, with layoffs, pay cuts and publication closures as advertising revenues dwindled, was expected. One of the latest casualties is the 42-year-old sports magazine, Cricket Samrat, that had, for decades, been a staple diet for followers of the sport, especially in India’s Hindi belt.

The magazine actually started as Khel Samrat, covering various sports back in 1976 at the time of Montreal Olympics. “Back then, cricket season used to be three or four months long and we would publish cricket-oriented special editions in the season,” founder Anand Dewan tells ThePrint. “A disgruntled reader angrily wrote to us to change our name to Cricket Samrat if that’s all we talked about, and we complied.” In November 1978, Cricket Samrat, one of the most iconic sports magazine in India’s history was born.

The glory days of the 1980s and ’90s

The monthly magazine was launched at a time when cricket in general was picking up pace in India, and the two went hand in hand, in a sense. Two instances in cricket saw the frenzy for the magazine touch its peak — once, when Team India led by Kapil Dev brought the men’s World Cup home in 1983, and again, when Sachin Tendulkar played his heart out and delivered that blistering knock at Sharjah in 1998, when India defeated Australia in the final.

“After ’83, we never really looked back,” Dewan says. This was also when access to television was limited, so Cricket Samrat became a major source of information, and the best way people could relive the matches. By the ’90s, it was the most widely circulated sports magazine in any language in the world, according to Dewan. This he says, he was informed about by Esquire magazine.

In 2010, the magazine had more than a million readers, according to Indian Readership Survey, and was still the top sports magazine.

Also read: Tinkle and Amar Chitra Katha, the comics we grew up with that grew up with us

Democratised access to the game

The Hindi-language magazine proved to be the go-to for Tier 2 and 3 cities as well as rural India to learn more about this complicated British game, with its many rules, its etiquette and techniques, that had completely taken over the Indian imagination.

The magazine played an important role in spreading the gospel of cricket in the Hindi heartland. “Imagine a boy or girl, who even doesn’t have access to a TV, computer or phone,” Pamul Kumar Joshi, a Kolkata-based marketing consultant says, explaining that “children then learnt the techniques employed by the best players in the world in the pages of this magazine, which was like a coach to them.”

For Joshi, who aspired to be a professional cricketer, but couldn’t pursue his dream because of an injury, the magazine served as the only source of information that would dissect the many rules of the game and techniques of players, and even write about controversial matches. “The match in Australia, when Harbhajan was accused of a racial slur against Andrew Symonds, nobody explained and revisited that controversy better than Cricket Samrat,” he tells ThePrint.

The magazine wasn’t just dedicated to first-class cricket either; it also provided space to up-and-coming players and gave a platform to state and district levels. “Nobody covered Ranji Trophy better,” Joshi says, explaining how it helped him find out which player was catching the attention of selectors and why. It also helped him ascertain which selector covered which division, what they looked for who he had worked with.

The magazine simplified the game for readers by using accessible language and explaining various stats of the game in detail with the help of graphics and pictures. “It made you more curious, and informed you more about the game than you perceived between the wickets.” Delhi-based lawyer Shantanu Chaturvedi recounts. “In the absence of the internet, Samrat was the go-to place to get hold of thorough statistics — who has scored how many centuries, which team is leading in test matches, the works. It was also an excellent way of developing a sound Hindi vocabulary.” he says.

Also read: Dharmyug, a magazine that served as stepping stone for aspiring writers, artists

Special features that made it a favourite

Even though he loved everything about the monthly, Chaturvedi had a bias for the pull-out posters that made the magazine a collectible. “The posters were bigger and better than any competitors like Sportstar,” he tells ThePrint. “They were truly iconic. There was one with Sunil Gavaskar and Kapil Dev holding the 1983 World Cup victoriously from a balcony. And one perfectly timed shot of Jonty Rhodes’ catch of English player Mark Ealham. They have to be my favourite.”

The magazine also had bigger, better posters, better quality paper and other pictures than any other Hindi magazine on the stands, says Chaturvedi.

Joshi reminisces how the magazine was a must for every aspiring cricketer: “It’d detail the health regimen of star cricketers, how they improved their game and what struggles they’d endured to reach where they are.” For him, what was written in Samrat was final, and he would blindly trust whatever the magazine chose to publish, from the time he was 16 years old right up until now, when the magazine decided to shut its press.

The magazine had already been struggling since the early 2010s, Dewan explains to ThePrint. Even with a million readers, it hardly had any advertisers. But the lockdown completely crippled the the publishers, and discontinuing the magazine was the only pragmatic decision they could take.

When we asked Dewan why he never opened a website for his magazine, his answer was simple: it was an unfinished project, left unattended when his son decided to leave the country and move to Canada. But Dewan hasn’t given up on his magazine yet. “We’re still exploring ways to resurrect it online, but we can forget about another print edition any time soon.”

Also read: Target — the kids’ magazine of the ’80s that has spawned fan groups in the new millennium