Meerut/Mainpuri/Prayagraj: Before Covid hit India, 25-year-old S. from Mainpuri was living a ‘normal’ life as a student in Noida. But when the country went into complete lockdown the first time, she lost track of her life. She is now one of the names in the mental health ward register at Mainpuri’s district hospital. The small rural district with a population of around 18 lakh has ultrasound, x-ray facilities and physicians, but it does not have a single psychiatrist or a clinical psychologist.

S. lived six months of the first lockdown in her apartment with extreme fear, horror and vulnerability. She developed a phobia. Then, she stopped stepping out.

“She started thinking that she will never be able to see her family, or that she will die in the apartment and her family won’t be able to see the dead body,” says Aruna Yadav, her counsellor who has been working in the non-communicable disease department since 2019.

The two years of pandemic-induced mental health trauma is overwhelming hospitals in small towns like Mainpuri, Prayagraj, and Meerut. Long dismissed as an urban phenomenon and stigmatised in smaller towns, mental health patients are not receiving professional, skilled help. Like earthquakes and natural disasters, Covid healthcare has also largely focused on physical needs. As numbers swell, the gap in mental health infrastructure in small and semi-urban towns is glaring.

Yadav recalls another mental health patient, a 44-year-old who lost his job during the pandemic.

“He suffers from insomnia. He told me that he goes to the market, and forgets the purpose of the visit.” He now needs a written list of things to do every day.

ThePrint accessed the register of the mental health ward of Mainpuri hospital. The data shows that five patients were registered in January 2021, which increased to 8-10 in August, 10-12 in September, and 14-15 in October.

Mental health problems are spiralling in small-town India – 2021 and the second Covid wave has just made it starker. ThePrint travelled to Prayagraj, Varanasi, Mainpuri and Meerut in Uttar Pradesh visiting district hospitals and mental health wards to assess the situation.

Also read: From Agra to Prayagraj, spike in suicides is the untold story of pandemic business distress

Bare bones

The Mainpuri hospital’s mental health ward has been dysfunctional for years, even though the hospital is part of the National Mental Health Programme, a scheme that was started in 1982.

Under this programme, eight posts in district hospitals are mandatory – psychiatrist, clinical psychologist, psychiatrist social worker, psychiatric nurse, community nurse, monitoring and evaluation officer, case registry assistant, and ward assistant. Along with these, a 10-bed psychiatric ward is also compulsory. Mainpuri has just three of these posts filled – there is Aruna Yadav, a counsellor who has a Sociology degree, Nirmala Singh who has a psychology degree, and staff nurse Mohit Singh.

“The Uttar Pradesh government has issued helpline numbers to address mental health issues. We generally refer the patients to Saifai (35km away) or to Agra (120km away) for treatment,” Chief Medical Officer Dr P.P. Singh told ThePrint.

Not only is there a lack of infrastructure for patients, but most hospitals also didn’t prepare for the mental health aftermath of the disastrous second wave of Covid.

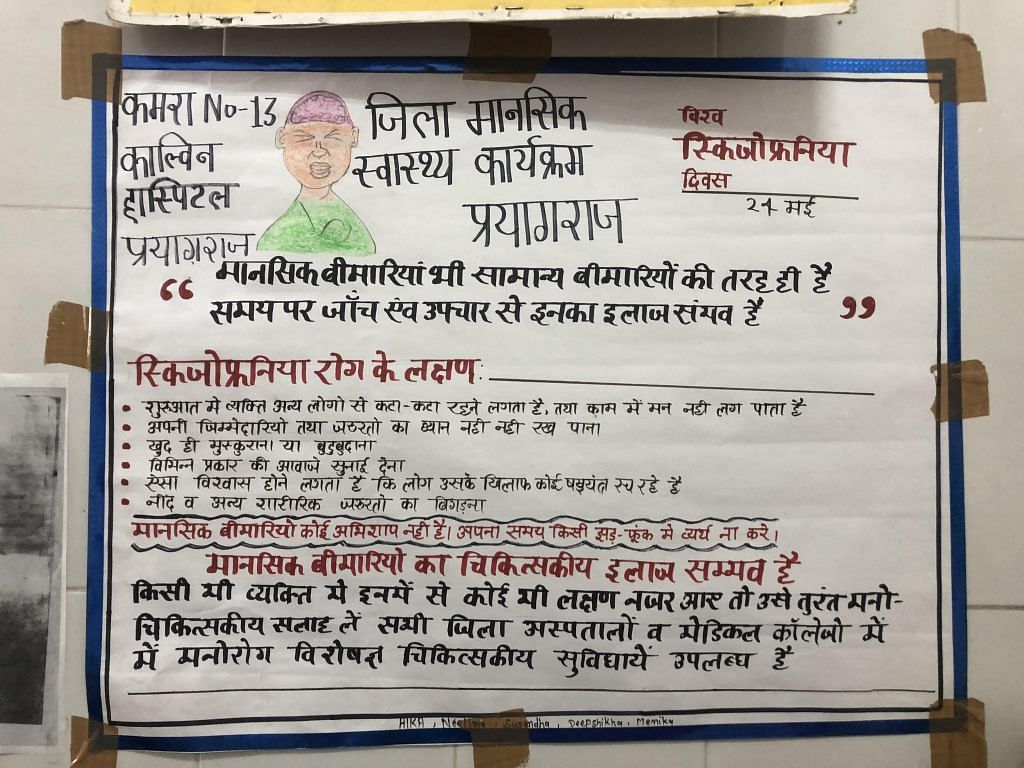

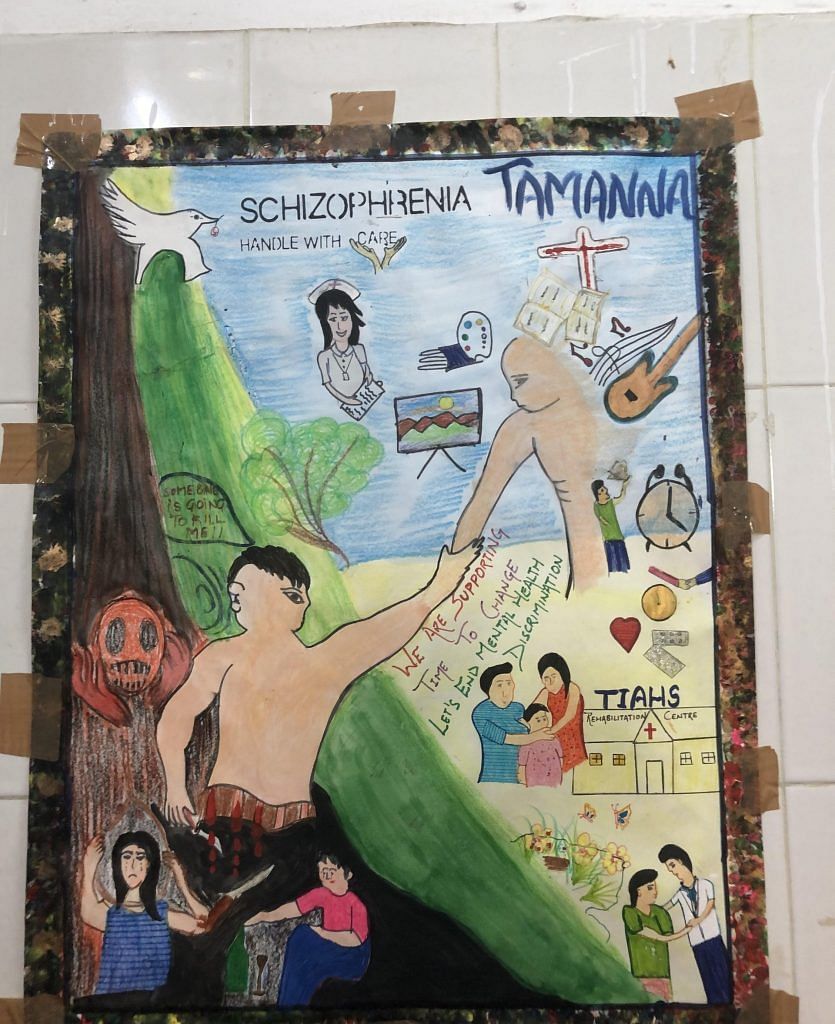

During the first wave, people who faced financial crunches, adjustment issues with the lockdown and interpersonal problems approached us, says Dr Ishanya Raj, a clinical psychologist at Motilal Nehru Divisional Hospital, Prayagraj. As a result, many mental health professionals came together and started tele-counselling. Central and state governments also started helpline numbers.

“But the second wave was devastating. Patients had to be stopped from committing suicide. Many of the people approaching OPDs at district hospitals were desperate for help,” Raj says.

The Prayagraj hospital has four mental health professionals instead of the mandatory eight. Three days – Monday, Wednesday and Friday – are spent in the OPD, and the rest of the week dedicated to outreach programmes at health clinics, colleges, schools, jails, and offices.

This week, 23-year-old K. from a well-to-do middle-class family is waiting for her third counselling session. Her parents visited the ward a month ago when a private psychologist referred them to the divisional hospital. They were told her case was “severe”.

“Her problem was detected six months ago when she started hallucinating. She told us that she sees people who died of corona around her, and spends her days in extreme fear that she is next,” says Dr Rakesh Paswan, who attends to her.

“She stopped eating anything from outside fearing Covid. The private psychologist prescribed medicines but she refused to take them because those are also brought from outside,” he told ThePrint.

There are several mental health patients whose old issues got triggered and became major disorders during the pandemic.

“Most are reporting insomnia, uncertainty, fear, anxiety and depression,” Dr Paswan said while attending to 23-year-old college student Abhay, who first came to the hospital to report a smartphone addiction.

“I spend 15 hours a day on my phone,” he tells me, his hands and legs trembling.

Back at Mainpuri, there are no psychologists. So, the physician in the JJ Ram district hospital attends to patients who report anxiety and depression. He asks patients to take proper meals and prescribes sleeping pills and anxiolytics.

“Ghabrane ki zaroorat nahin hai (there is no need to worry),” he tells them.

Also read: Covid and containment worsened women’s mental health, increased food insecurity in India

Acute shortage of psychiatrists and psychologists

Every natural calamity or epidemic has a psychological effect on a large population because people suffer a common feeling of loss, financial problems and uncertainty. Bhopal gas tragedy survivors suffered mental trauma for decades. Cyclone Fani in Odisha was followed by anxiety, depression and trauma.

But in districts like Mainpuri, accessing a professional mental health expert is a huge task and exposes the gaps within the system.

According to the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare’s reply in Parliament in 2018, “There were only 898 psychologists against 20,250 required in the country. Less than 900 psychiatric social workers against the 37,000 needed and 1,500 psychiatric nurses against 3,000 needed in the country.”

A study conducted by Lancet showed that Covid had triggered depression and anxiety cases. In India, such cases saw a spike of 35 per cent. In 2020, there were “76.2 million cases of anxiety disorders and 53.2 million more cases of major depressive disorders”.

Dr U.B. Singh, additional chief medical officer of Agra, says that stigma is also a major factor. “Rural and semi-rural areas are far away from discussing mental health,” he says.

“Mental ho gaya hai. Pagal hai. These are the type of labels that are commonly given to those who seek medical help. I am afraid that the ones not approaching us are far more in numbers,” Singh added.

However, Dr Vibha Nagar emphasises that at least the middle class in small towns are admitting that there is grief.

Also read: Obesity and depression are related. The world is feeling the weight

Grief, guilt and trauma

The situation in Meerut is alarming. A town so close to the national capital, with a population of 34 lakh according to the 2011 Census, has only a few dozen private psychologists and a handful of clinical psychiatrists. It wasn’t ready for the massive spike of people seeking medical help for mental health conditions during the pandemic.

In April-June 2020, the Meerut district hospital reported 158 cases out of which 16 patients were suffering from severe mental disorders and three were at suicide risk. By April-June 2021, the numbers increased to 949, out of which 174 were suffering from severe mental disorders and 17 were at suicide risk.

The numbers got starker. By September 2021, there were 3,354 cases out of which 452 were severe mental health disorders and 30 patients were at suicidal risk.

“They are not able to cope with grief and guilt after their loved ones died. They ran pillar to post to find a bed. Now, there is fear of a possible third wave and this has again triggered several cases here,” Dr Vibha Nagar, a clinical psychologist under the National Mental Health Programme told ThePrint.

She is counselling a 67-year-old man suffering from extreme trauma and fear. During the peak of the second Covid wave, he consumed so much news about the virus that images of the red virus started hounding him. The graphics shown on TV started looking real. He cried during the video counselling session that he can’t go to the bathroom at night because he fears the virus will be waiting for him.

“I can see his red eyes. He has become sleep deprived. He has stopped reading newspapers and suffers from panic attacks,” Dr Nagar tells me.

Another 45-year-old college lecturer lost her mother to Covid. It has made her pessimistic. Now she does not believe in humanity and blames herself for the death.

The numbers on the hospital register are much fewer than the calls Nagar and other clinical psychologists, psychiatrists and counsellors receive every day since the second Covid wave hit the nation.

“My phone rang 24 hours,” Nagar says.

The Meerut district hospital mental health team recently saved a Rajasthan businessman from committing suicide with his whole family.

“He needed to be told why he and his family should live.”

(Edited by Neera Majumdar)