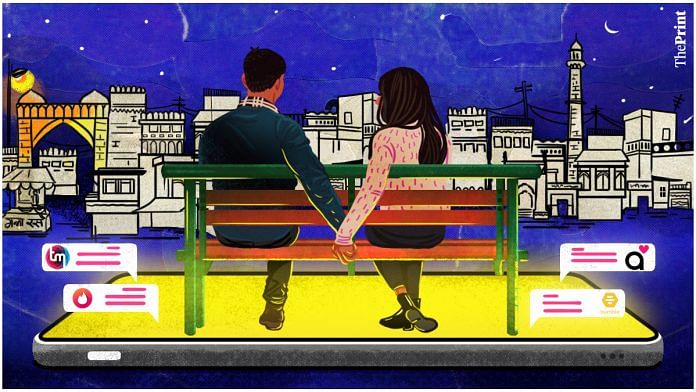

Swati sneaks over her shoulder before grabbing her boyfriend’s hand. She isn’t dressed for a date, though. The 22-year-old is in gym clothes, and her white sports shoes glow in the dark of the night. She’s told her parents she’s at the gym, but she’s actually meeting her boyfriend in Chandra Shekhar Azad Park. After all, it is Prayagraj, Uttar Pradesh, where everybody knows everybody.

They haven’t met in ten days, and this one-hour mid-week window is all she could steal away.

Swati and her boyfriend entered the Prayagraj public park from a side gate and found a bench that was secluded enough. They lower their voices when they hear passersby, trying to melt into the dark. The only light around them is the glow from their phones — they’re trying to take a selfie for her ‘close friends’ list on Instagram, where they met.

If her elder brother finds out about this, she says, she wouldn’t be allowed to leave her house. She doesn’t care what people think about her — but her family does.

Dating in young India’s small towns is secretive, saucier, skilful, and state-of-the-art. People are more experimental, open, and curious but are still held back by strict families and a judgemental ‘aunty-uncle network.’ The age-old excuses and lying to slip away on a date are still in play, but social media has added both an extra layer of required stealth and a larger pool of partners to pick from. It has upped the ante and the risk.

“What’s changed is choice,” says Vivan Marwaha, author of What Millennials Want: Decoding the Largest Generation in the World, a book on the attitudes, aspirations, and desires of millennials in India. “The data shows that arranged marriage is as common as it was earlier. The pre-arranged marriage part is where there’s a choice to talk to people, whether physically or virtually. Even if the outcomes haven’t changed, there’s now at least a choice.”

But even so, couples in tier-2 and tier-3 cities don’t have many options when it comes to dating. So they make do with what they can: They kiss and cuddle in multilevel parking lots, hide behind public monuments, and lounge in parks after dark. Sitting at a coffee shop or restaurant runs the risk of being seen, so they are always on the move, preferring to be in each others’ company rather than enjoying the ambience. And in Allahabad, Nehru’s Anand Bhawan is a dating hotspot.

Meeting new people is another challenge: Social circles are limited and usually expended. Many choose to frequent public spaces or slide into Direct Messages (DMs) on Instagram. Others prefer to flirt on Facebook, Zoom, and even YouTube comment sections. Deepika, a 24-year-old student at Ananya Academy in Prayagraj, forced her friends to move their hangout spot to another public park so she could check out “new, cute men.” She’s wary of dating apps because she can’t trust the people on them.

“People don’t take advantage of Tinder and Bumble here in Allahabad. They take advantage of the dark,” says Ayush Srivastava, a student at Allahabad University.

Also read:

The door to dating

Every social media app has now become a dating app: It’s what people use to meet and connect with others. Sliding into DMs has become the standard modus operandi of adults looking to date.

“Technology and social media have enabled people to look beyond their social geographies. They are not confined to their physical space,” says Marwaha. The implications of this are that more and more people are spending time online, finding comfort in communicating from behind their screens.

Dating apps like Tinder and Bumble haven’t made inroads into India’s tier-2 cities and smaller towns. According to Statista, the dating app penetration in India was only 2.23 per cent at the end of 2020. However, this dismal number doesn’t mean that apps aren’t being used for scouting potential partners. Besides Tinder, Bumble and Hinge, users are turning to Indian dating apps like Aisle and TrulyMadly—but class differences often play spoilsport.

“It is an elitist space,” admits Agrima Sharma, a 21-year-old resident of Lucknow. “I’ve run into lots of unpleasant people on apps.”

She’s catching up with her friend, Pratul Chaturvedi, at one of Lucknow’s fancier offerings: Summit—a building crammed with cafes, bars, and restaurants—that has become ‘dating central’ for the city’s youth. Chaturvedi, also 21, met his girlfriend on Tinder during the Covid-19 lockdown in 2020 in Lucknow. The two seriously pursued each other only after realising they had many mutual friends.

The lockdown was a huge catalyst for online dating, as thousands of young people left their big city lives to return to the comfort and security of their hometowns. TrulyMadly, for instance, reported a tenfold growth of revenue in 2020, while video dating on Tinder observed a marked rise in India. These statistics, however, are mainly restricted to tier 1 cities like Hyderabad, Chennai and Bengaluru. According to a survey conducted by YouGov across India in 2021, which analysed Bumble data, 72 per cent of respondents think it is possible to find love online, while 45 per cent of single respondents think online dating is the standard way of pursuing romance.

Another 2020 survey, also conducted by YouGov in collaboration with Mint and Centre for Policy Research (CPR), found that 19 per cent of millennials weren’t interested in either marriage or children, while a further 8 per cent wanted children but not marriage. Since this survey was conducted right after Covid hit India, anxieties about the future shaped the respondents’ answers. Aversion to marriage was higher among older millennials than younger ones, and nearly four out of 10 millennials who wanted to get married were okay with an arranged match. Seven of 10 Gen Z adults said they’d prefer a love marriage.

The survey was conducted across 184 towns and cities to accurately gauge India’s romantic pulse. Bumble, for one, has started addressing the nuances of dating in cities like Ahmedabad with an out-of-home campaign. It has introduced features like ‘interest badges’ and ‘language badges’ to showcase user personalities and linguistic preferences.

“We have observed single Indians take charge of their dating journeys increasingly across India, including tier 2 and tier 3 cities,” says Samarpita Samaddar, Bumble’s communications director in India. After the pandemic, people have become more mindful of what they are looking for in a partner, particularly women, Samaddar adds.

But like Sharma and Chaturvedi, most people on dating apps prefer to meet people they have mutual friends with. Barriers like class and language immediately show up, further dissecting the limited dating pool.

A new app, HiHello, is trying to change this. Launched in October, it is a dating app ‘for Bharat’. It offers 11 language options and aims to reach the upwardly mobile, aspirational generation of Indians, not just English speakers.

Also read:

Dating apps for Bharat

Startups are beginning to address small town India’s routes to romance.

“Why is there no tech solution for relationships? That was the genesis of our app,” says Shyam Tallamraju, founder of HiHello. “Everybody talks about Gen Z. But in India, we have Generation Bharat — and nobody is really addressing them.”

Jio, UPI and Chinese smartphones form the holy troika that has changed India’s landscape in the last five years, according to Tallamraju. And it has captured the attention of all Indians, 90 per cent of whom are comfortable in their native language.

Aisle has been around since 2014 and was the first to introduce ‘vernacular dating’ to India. It has a user base of 15 million people — of which 40 per cent use its vernacular platforms: Arike (Malayalam), Anbe (Tamil), Neetho (Telugu) and Neene (Kannada). Aisle is for people focused on ‘high-intent dating,’ which is a cross between casual dating and traditional matrimonial sites.

“When you’re phone savvy — which people in tier-2 and tier-3 cities in India are — you look for solutions that are convenient and available at the click of a button,” says Able Joseph, founder of Aisle. “Online dating doesn’t have the same logistical constraints as offline dating — if you can play PubG in a small town like Kottekad [in Kerala], why can’t you use an app to meet your future partner rather than looking at newspaper cuttings and whatnot.”

Joseph also took his cues from the success of romance movies. “Coupled with the data from Aisle, we decided to launch our first vernacular app in 2019, which was Arike in Kerala. The culture isn’t the same as what it is in California, and it’s important to cater to that.”

It is a market that wants to be addressed. HiHello is still brand new, but 75,000 people have already downloaded it. It is currently only operational in UP, Haryana, Bihar, and Rajasthan. Around 70 per cent of the profiles use Hindi — Tamil was only launched in the second week of December, so it is still too early to gauge its success. As the app grows, it will consider introducing ‘caste-based’ features — something that’s often a barrier in serious relationships.

Until then, they’re focusing on learning what ‘Generation Bharat’ wants.

Also read:

The dating lives of Generation Bharat

On their brisk winter afternoon walk, aunties and uncles sniff and turn away from a couple holding hands on a bench in Meerut’s Suraj Kund Park. The park has sprawling lawns and few corners to hide in, making it a more family-friendly and less couple-friendly park.

“It’s not like we have a problem with all this,” says Roopa, 64, gesturing vaguely. “The question is why they have to do it in public! They have no shame!” She does not respond to where couples should be meeting and dating instead but thinks the younger generation “should be more modest.”

Lying is a necessary part of the dating game — especially if hopeful date-goers live with their parents.

A group of six friends lounging in the winter sun at a public park in Prayagraj have a fair share of tricks up their sleeves. One of them tells her parents she’s going “shopping” when she’s actually meeting her boyfriend — she makes sure to return with something like vegetables, milk, or bread so that her parents don’t get suspicious. Another tells his mother he’s going to the library while he spends some “private time” with his girlfriend at a hotel. Yet another generously extends the timings of her tuition classes to squeeze in a date. All of them are open to sex before marriage/pre-marital sex. They have all covered for each other.

“I’d say I’m going for Physics practicals, but actually, I’m going for Biology practicals,” jokes Shaurya Pratap Chauhan, 23.

They archive risky WhatsApp chats so nobody can snoop on their phone. One of them has a fake Facebook profile which he uses to chat with women — fake because his parents are his Facebook friends and keep an eye on his social media activity. They all make sure to keep their phone with them, on silent or in airplane mode, to avoid awkward situations. None of them use dating apps.

“There’s usually a ‘responsible’ friend that a parent trusts,” says Krittika, an 18-year-old Prayagraj resident. “And it helps to take them along as a third wheel because people are bound to recognise you here. It’s not always the city. It’s the mentality, too,” she adds.

Prayagraj has a large student population attending coaching classes, many of whom come from smaller pockets of UP. This segment has a much easier time being in public relationships than local people: Their partners can come to their PG accommodations or apartments without much hassle. One couple — aged 24 and 27 — feel comfortable kissing in public but say they’re always judged. Another couple, aged 20 and 21, from Patna and Bhopal, practically live together in Prayagraj’s Gangotrinagar.

Residents don’t have that luxury, of course. And then there’s the added pressure of getting caught, either by someone who knows them or by local authorities. Security at Chandrasekhar Azad Park, for example, is always on the prowl for unbecoming behaviour, especially after dark.

“We step in whenever we see ashleel (vulgar) activities at night and ask people to come sit in the light. It’ll be safer for them, too,” says Govind Singh, a police officer from Georgetown police station assigned to oversee park security.

Singh also runs the local ‘Anti-Romeo Squad’ — an initiative by the UP government to protect women and prevent eve-teasing. For him, safety is a bigger priority than safeguarding couples’ privacy.

“The difference between a city like Delhi and a city like Prayagraj is about 20 years. We are still catching up,” he adds.

Also read:

Fear grips young couples

What happens if their parents find out?

“If our parents find out, we won’t break up,” declares Muskan, 23, who’s in a long-distance relationship with her boyfriend in Odisha. She says her parents will do their best to end the match if they found out.

The fear of being caught by suspicious parents seems to be superseded by the fear of hurting their parents’ pride — it’s why honour killings are so common, explains Muskan and her friends Deepika and Niki.

“Neighbours are the ones to watch out for,” says Prince, a 22-year-old musician from Prayagraj who’s planning on moving to Mumbai sans his girlfriend. He plans to ‘make it big’ before taking the next step in their relationship, which is a complete secret. “It doesn’t affect us, but it affects our parents and their social standing.”

Caste, religion, and class background suddenly become glaring obstacles. Niki’s relationship is a secret to her family, but her boyfriend’s family knows about them. “He’s in the general category, I’m scheduled caste,” she says. “So it could be a problem, even though we are both well-educated.”

Many young people are in long-distance relationships with people they met online. Shweta and Kajal, two students at Meerut’s Chaudhary Charan Singh University, met their boyfriends on social media: Shweta is 22 years old, met her boyfriend on Facebook, and has been dating him for eight years, while 20-year-old Kajal met her boyfriend of three years on Snapchat. Neither of their parents know, and they don’t intend to tell them. Shweta has her eyes set on marriage, though.

Part of the allure of long-distance dating is that it’s out of their family’s watchful eye: It’s safe to orchestrate a romance online, through words and emojis on-screen. And if their parents are watching them, they’re watching their parents right back. It’s why so many people don’t want to broach the topic of dating with their families: They hear how their families talk about young people —especially young women— in relationships.

Monika Chandra, a 45-year-old mother in Meerut, only needs to hear the word ‘date’ for her anxieties to come pouring out. She’s mother to two young daughters — 21 and 15, respectively. She remembers a story about a neighbour’s daughter from four years ago: She allegedly lied to her parents to go out and meet boys until one day, an older man in a restaurant reportedly murdered her.

“She obviously had a relationship with him. I feel bad because she had no sense, just meeting men without thinking of the consequences,” says Monika. “My daughters are not like this. They don’t lie to me.”

She clarifies that neither has a boyfriend. “The thing is, I’m their mother first and then their friend. They can definitely choose who they want to be with. Why should they struggle like we did?” She has no solutions for how her daughters can meet good men, though. She’s also never heard of dating apps.

This illusion of choice does shatter sometimes, for both parents and their children. Muskan’s brother wanted to marry his girlfriend and told their parents about it. The match ultimately didn’t work out because his girlfriend’s family had issues with their relationship. As the topic of marriage came up, Muskan’s uncle asked her father whether she had any prospects. “My daughter doesn’t do stuff like this,” she remembers him saying disdainfully.

“But I am in a happy, healthy relationship,” Muskan says in a soft, sad voice. “I am the kind of woman he looks down upon at home. That’s why I can never tell him about being in love.”

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)