New Delhi: The 1990s was a decade of a heady political and caste revolution. Dalits in Uttar Pradesh were building defiant blue Ambedkar statues in public spaces against all odds and voting for their own behen Mayawati’s Bahujan Samaj Party. Two decades later, many Indians are asking ‘Where is that revolution now’?

The BSP is in a slide, and Dalits of the state are voting for the BJP of Yogi Adityanath, Narendra Modi and Amit Shah.

There is almost a tinge of betrayal with which some political observers and BSP admirers have viewed this significant political shift in the voting behaviour of UP Dalits.

The question has become especially more frequent since the 2017 Uttar Pradesh elections and the 2019 Lok Sabha elections. It is also the subject of a new book called Maya Modi Azad: Dalit Politics in the Time of Hindutva by scholars Sudha Pai and Sajjan Kumar.

The answer, according to the two authors, is that it is a natural inevitability, and not necessarily a negative development to bemoan. It is also a sign of a confident, middle-class Dalit that is not beholden to one political party or leader.

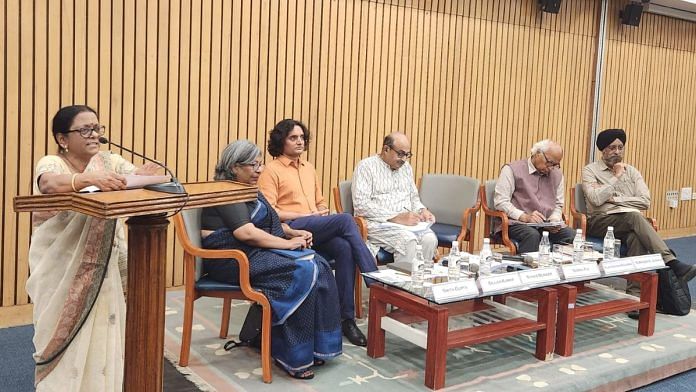

“Like other privileged and better-off communities who shift from one party to another, Dalits are also adopting the same confidence. So rather than lamenting the fragmentation, we have explained it and, in a way, celebrated it,” said Sajjan Kumar, Fellow, Nehru Memorial Museum and Library, during the book launch at the India International Centre in New Delhi this week.

There is no exceptionalism to this change in Dalit political behaviour in Modi’s India. Similar questions have been asked about African American support to the Republican party, and even Donald Trump. And also about the Indian LGBTQ+ community voting for Modi.

The shock and betrayal arise from an expectation that a marginalised community remain steadfast in the revolution and agitation mode. It is a sort of fetishisation of the group. So a Dalit vote for the BJP is largely viewed as a reversal of the gains of a movement, or as a step back from Ambedkar-ite goals.

But questions about what comes after symbolic gains in a movement are universal — what comes post-dignity, post-civil rights, post-middle class and post-affluence.

Also Read: Quasi coronation of nephew? Extra sofa on Mayawati’s dais triggers succession buzz in BSP

Identity to economics

BSP arose from four decades of the creation of the Dalit middle class, mostly as a result of reservation policies. But its decline is also, ironically, a logical consequence of the success of its agenda of dignity and self-assertion, the book says.

The impact of the 1990s globalisation in UP came late because of a decade of identity politics; and when it did, the desire for social justice naturally led to economic aspirations. This is where the BSP tripped, it could not morph from an agitational, angry party into one of economic opportunities.

“By the time Mayawati attempted her sarvajan experiment, she had raised more expectations among the Dalits than could be fulfilled by the party in five years,” said Sudha Pai, a JNU professor. Today, economic aspiration and Hindu cultural integration are driving the new Dalit politics in UP in the post-BSP phase, she added.

The social deepening of democracy and confidence that the BSP heralded has led the community to an era of political choice and agency. Instead of voting en bloc for the BSP, the community is now politically fragmenting — along sub-regional (Poorvanchal, Bundelkhand and western UP), generational and sub-caste categories (Jatavs, Khatiks, Pasis, Valmiki).

Also Read: How pro-BJP & pro-BSP Dalits differ: One embraces Bhakti-era Ravidas, another the Buddha

A tactical shift

Many expected two decades of Ambedkarite Dalit movement in the north to mirror the trajectory of Periyar’s self-respect movement in Tamil Nadu. It’s another matter that the atheist campaign didn’t travel far. In fact, when Ram Nath Kovind was made the President, he was viewed as not being Dalit enough because he was comfortable with Hindutva. The new book rejects this binary of Dalit identity and religion.

“The way the question of secularism is being posed today and then expects the subaltern community of OBCs and Dalits to choose secularism misses the point that there are multiple modes of religiosity,” said Sajjan Kumar. “And Hindutva is not necessarily following a ritualistic and Brahminical religiosity. More often than not, it is willing to cater to folk religiosity, which has more resonance among the subaltern community.”

“Three Dalit communities—Pasis, Musahars and Nishads—were particularly targeted by linking them with the Ramayana and Ram,” the book says. “What we are witnessing in UP is ‘politically induced cultural change’.”

The other big question the authors tackle is how the Dalits protest against atrocities on one hand, but also vote for the BJP when the elections are held. It is similar to how puzzled Americans were that months after George Floyd was killed and the Black Lives Matter protests erupted across America, some Black men still voted for Trump in 2020. It showed that there exists a “a gulf between how the “woke” Left processes racism and how many people in the real world do,” said The Atlantic. And policy mattered to voters more than “rhetorical value on race and racism.”

In UP, the violence against Dalits is often blamed on dominant caste groups in the villages today, and not necessarily on the BJP. So, the shift to the BJP is tactical — a sort of protection from Samajwadi Party-emboldened OBCs who are hostile to the rise of Dalits — and ideological.

One popular way of explaining away this change in Dalit voting behaviour is to say they are getting the benefits of Modi and Yogi’s welfare freebies — i.e. they are the beneficiary community or the ‘labhaarthis’.

The ‘labhaarthis’ is an insulting term, and creates structures of dependency, said Surinder Singh Jodhka, JNU professor. “It won’t last long.” The audience clapped.

The other time there was a resounding applause was when politician Sudheendra Kulkarni said that the expectation of a separate Dalit power creating a separate politics was bound to fail. “What defeated the BSP was the diversity of India. And the same diversity will defeat BJP too someday.”