New Delhi: Mitchel Abdul Karim Crites was at the shrine of Sufi saint Khwaja Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya in New Delhi when he first paid attention to its intricate jalis. The American art historian was entranced by the playful patterned interplay of light and shadow filtering through the pierced screens, the signature architectural style of the Delhi Sultanate and the Mughals.

The city of djinns became the city of jalis.

“I was completely blown away by its intricate geometry. Delhi is a city of jalis. From 13th-century architecture to contemporary ones, no other city has so many of them,” said Crites at the launch of Navina Najat Haidar’s book, Jali: Lattice of Divine Light in Mughal Architecture, at the India International Centre (IIC) in New Delhi.

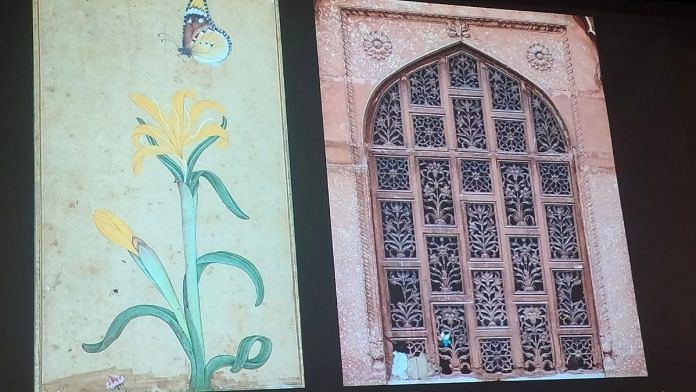

As the Islamic art department curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, Haidar has studied jalis in detail. She finds them one of the most intriguing elements of Islamic architecture because of the metaphorical importance of light. Laden with symbolism, jalis are the warp to the weft that is light.

She gives the example of the Qibla wall facing Mecca at Sidi Saiyyed Mosque in Ahmedabad, Gujarat, which was built in 1572–73 AD.

“Above the mehrab [a niche indicating the direction of Mecca], you have these two screens that hold a very important place in the mosque. They are not there to filter light alone for some practical reason. They bring light to the worshipper’s world,” Haidar said.

Her book is the culmination of capturing the perfection of Islamic architecture. Crites was the pivot. He introduced Haidar to Abhinav Goswami, a temple priest who is also a brilliant photographer and a trained archaeologist.

Goswami’s photos transform the book into an album, mapping the long story of perforated screens that adorn India’s mosques, temples, palaces, forts, tombs and even benches.

Also read:

Photographing jalis

When it comes to getting the perfect shot, Goswami has the patience of a cat stalking its prey—in this case, sunlight. It had to be just right.

“We had two sessions at the Agra fort, one during mid-March to mid-May and another in October. In March, the light is too crisp, so I had to wait for the October sun because it’s the only time light hits half of the jali. You could see shadows. It gave both shock and pleasure,” said Goswami.

His favourite photos were part of a slide show presented by moderator Pramod Kumar KG, curator, author and co-founder of Eka Archiving Services.

One of the photos Kumar showcased came from Goswami’s personal collection – a picture that he took 30 years ago at a Vrindavan temple. A jali of dainty white flowers encircled the idol. It is one of the many examples of syncretism in India.

“When I see this, I see a fusion of Mughal and Hindu traditions. It represents the fusion of the Ganga-Jamuna tehzeeb, which we must never allow to disappear,” Crites told Goswami.

It would take artisans more than eight hours to build the fresh flower jali called phoolon ka bangla. According to Goswami, they would quickly tie the delicate flowers into intricate patterns, careful not to let them wilt. However, this unique jali-making tradition, started by Vaishnavites in the 16th century, has consistently declined since Goswami took his photo.

Also read:

Artisans and patrons

Goswami, Haidar and Crites scoured cities and states for lesser-known jalis that have faded from public memory and records—some they found in New Delhi itself, some even in Nuh, Haryana.

“Nuh has some of the most important buildings with designs mostly taken from the 18th century,” Crites said. One of the photos he chose to highlight was an abandoned tomb in Nuh, which he juxtaposed with a palace in Iran built toward the end of the 16th century. Both had similar cut-out jalis in the shape of gulabpash (rose water sprinklers).

An added complexity to artwork is the heavy influence of its patrons. And Haidar places the patrons of the jalis at the centre. In the book, Haidar uses centuries-old paintings and quotes from Sufi poets like Amir Khusrau to explain their aesthetics, ideas and wants.

One of Haidar’s chosen paintings brings comic relief. Here, Mughal emperor Jahangir is seen embracing his Iranian frenemy, Shah Abbas, whom he never met in real life. Jahangir is seen proudly standing on a lion’s back, while the less opulently dressed Abbas, standing on a lamb’s back, is almost falling into the Mediterranean Sea. But the double halo behind them–solar and lunar–is the reason Haidar added the painting to her book about jalis.

The Mughal fascination with divine light is on grand display in this artwork.

“It reminds us that the symbolism of light is not just restricted to architecture. There’s an integrated approach and sense of aesthetics based on the identity,” said Haidar.

But it is the artisans who truly hold the key to jali designs. And even though the old masters have died and the art form is now endangered with fewer young people willing to learn it, jalis are still being made in India. Crites works with many of them in Agra, Jaipur and Makrana. In fact, one of the craftspeople, Ustad Mohammad Siddiq Bhati, was invited to launch the book with the author and curator.

“I had a commission to make a dozen jalis for a mansion in London. I took the carver from Makrana to the Taj Mahal, and we sat on the floor and touched the jalis. I told the artisan to carve one like that, but he said he couldn’t do it because it seemed too difficult,” Crites recalled.

The art historian still provided marble and photographers to the craftspeople and promised to return in a month. And when he came back, Crites was surprised to find that they had captured every tendril of the design.

“They haven’t looked back since,” he told an entranced audience.

As the discussion progressed and panellists skipped naming some hidden jali sites in the capital, Delhi-based Scottish historian William Dalrymple was quick to probe. Crites responded with examples – from the Tomb of Imam Zamam in Qutub Complex to the Anglo Arabic School and Delhi College near Ajmeri Gate.

“If you ever want to have a ‘jali time’ in Delhi, Nizamuddin complex is the best place to be,” Crites added.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatii)