In the courtly setting, jalis served to screen off the zenana (women’s quarter) from public gaze and were employed in almost all the forts and palaces of princely Rajasthan. While they had the desired effect of segregating the sexes, in the artistic imagination jali screens also sparked a sense of mystery and allure for what lay beyond. Life behind the jali screen became a point of fascination partly because it was the most powerful and inaccessible women who were concealed from gaze. A painting from the Mandi Bhagavata reveals the social order of women at court, where those of less exalted status are prominent while the elite are glimpsed through pierced screens (fig. 1). Raja Kansa is shown at centre, listening to the prophecy communicated by an old duenna while other women attend on him and provide courtly entertainment.

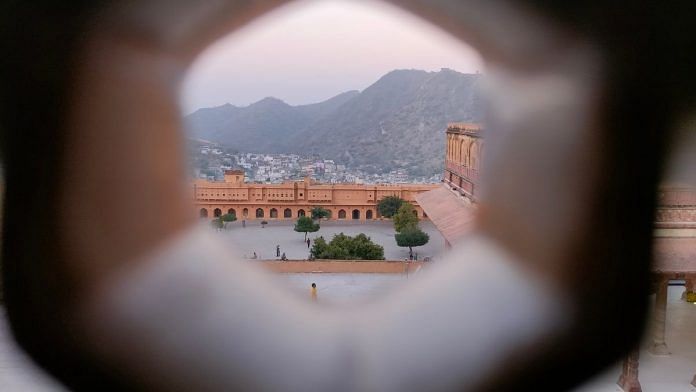

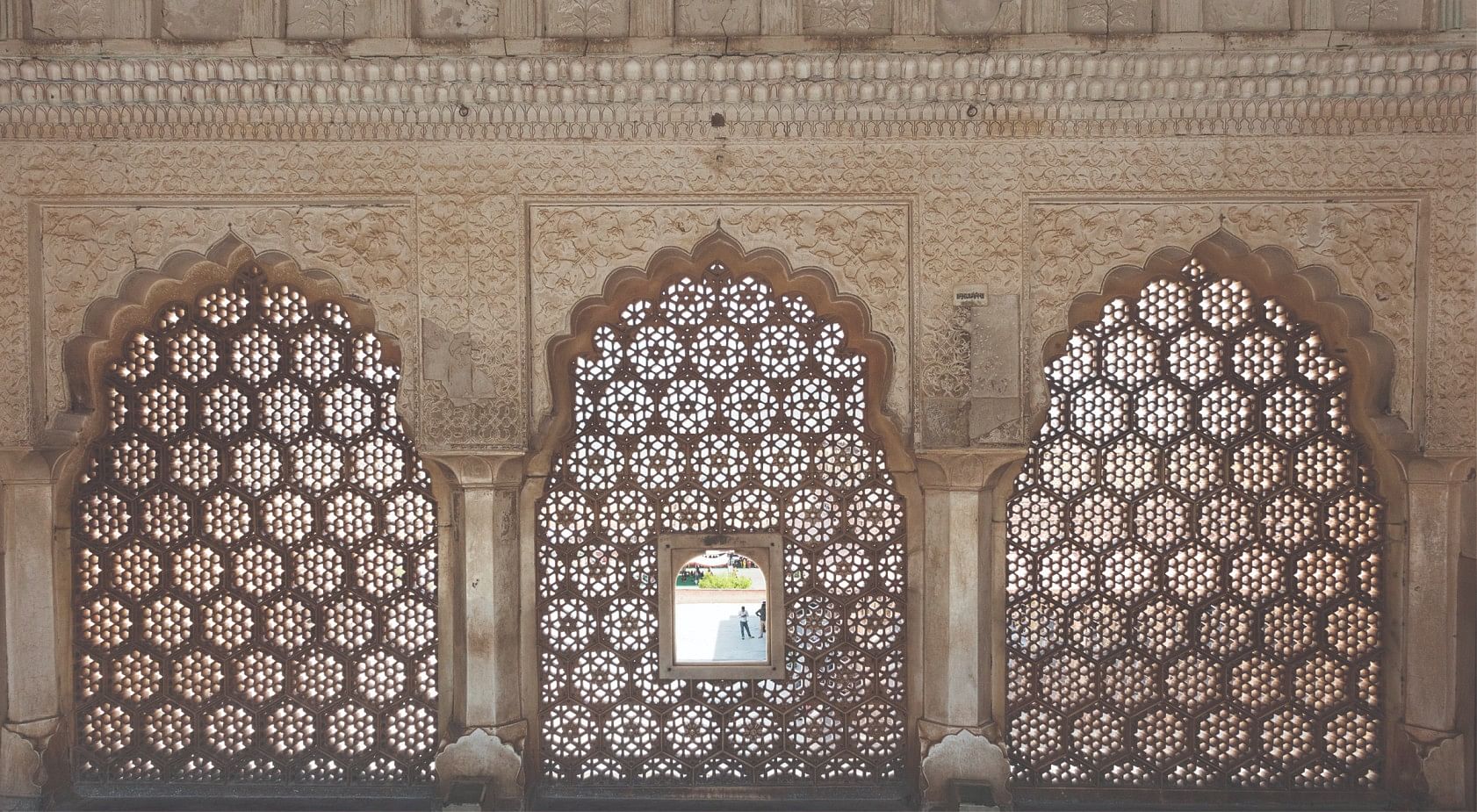

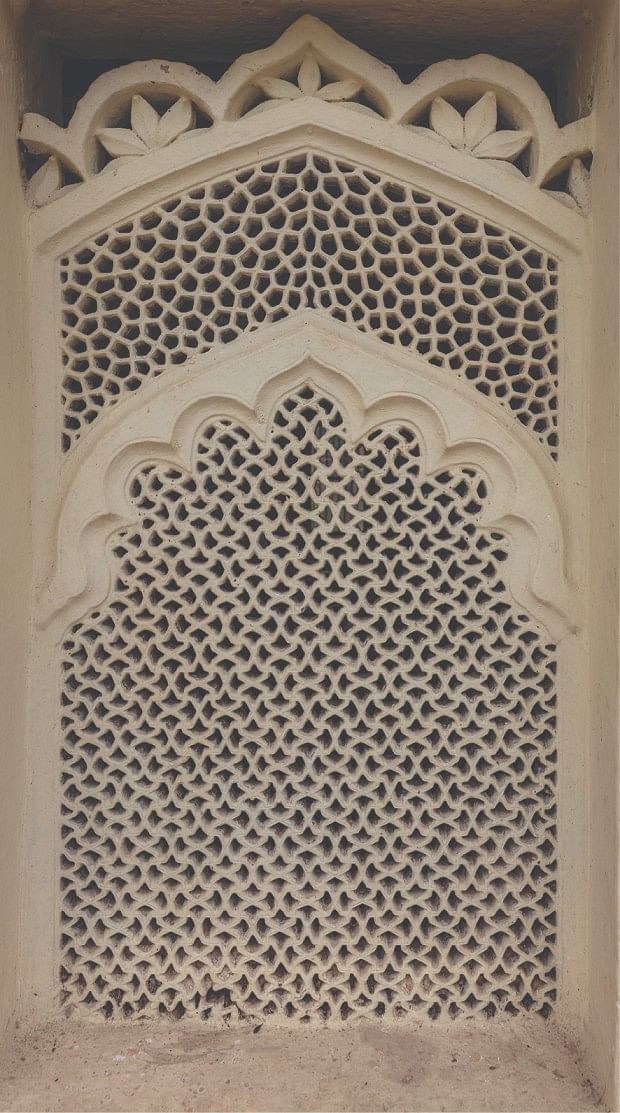

Flanking this scene are tall red jalis—possibly indicating pinajra-kari (woodwork) of the Kashmir region—shielding the secluded world of his wives but offering a glimpse through a little window opening. The manner of creating a cutout window in the middle of a jali screen appears in many architectural compositions, including in a large geometric and floral jali wall at Amer Fort (fig. 2).

Jalis allowed women to be part of wider courtly spectacles and events, particularly as some balcony screens were carved at a downward angle that would provide arena or street views. The literary imagination too was fired by the metaphorical possibilities of the jali. Among them is the conceit of a building dressed as a veiled woman. Jalis, with their interlace patterns that resemble woven textiles, can be seen to act as a veil for women in the zenana quarters. Behind the jali, women were active writers of Persian masnavis, Urdu ghazals, Braj Bhasha poetry and other forms of literature. For example, at the court of Kishangarh, Bani Thani or Vishnupriya, beloved of the poet prince Savant Singh, was an author in her own right. In a Kishangarh painting of the mid-eighteenth century, she appears in shadowy form behind a screen in a pavilion while the prince gazes up at her from a garden terrace below).

The desert forts and palaces of Rajasthan are famed for their jali work, where lengthy facades are covered with intricately carved screens that are integrated alongside dense carving and other forms of ornament. Typical of the Rajput style was the combination of a deeply curving bangla-eave style roof or cusped arches surmounting the jali screen. One of the most recognizable buildings of Rajasthan, the Hawa Mahal (Palace of the Winds) in Jaipur offers a spectacular facade featuring these elements. Shaped like the rising crown (mukut) of Krishna, the pierced facade allowed breezes to flow and offered its occupants views of the Pink City’s street life while integrating coloured glass into the openings.

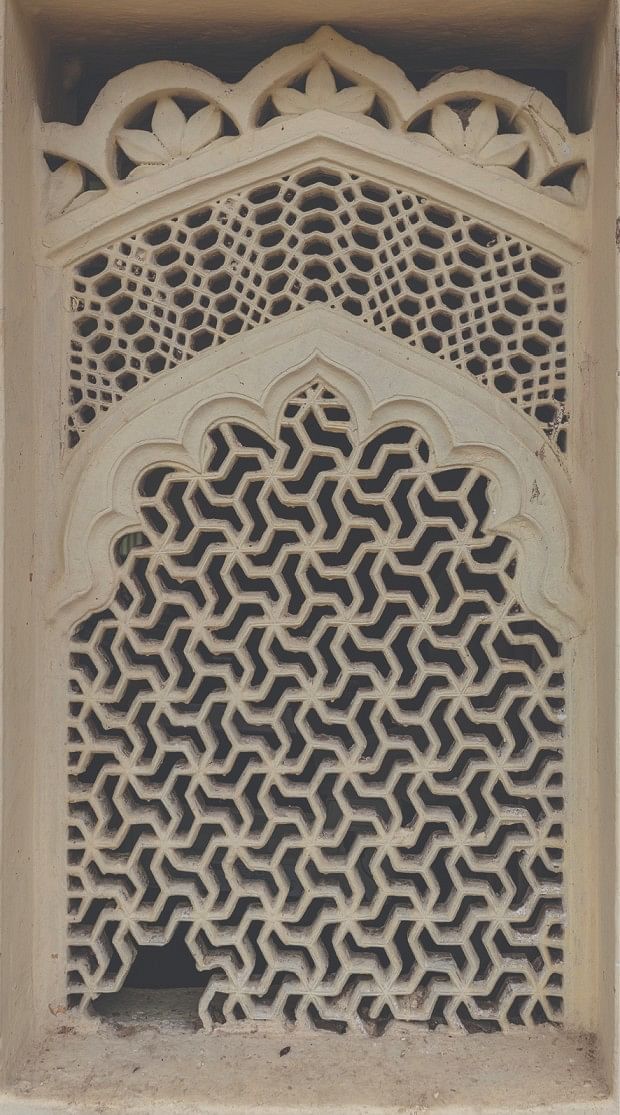

The medieval city and fortress of Jaisalmer feature elaborate perforated screens carved in the typical golden stone of the region which provide relief from the fierce sun of the desert. A dazzling play of geometrical patterns creates a filigree facade through which women of the court would have gazed out. A central open balcony allows for a space where a royal male figure could be seated, as depicted in paintings.

Also read: Travelling storytellers from Bengal – How Patua artisans preserve oral histories

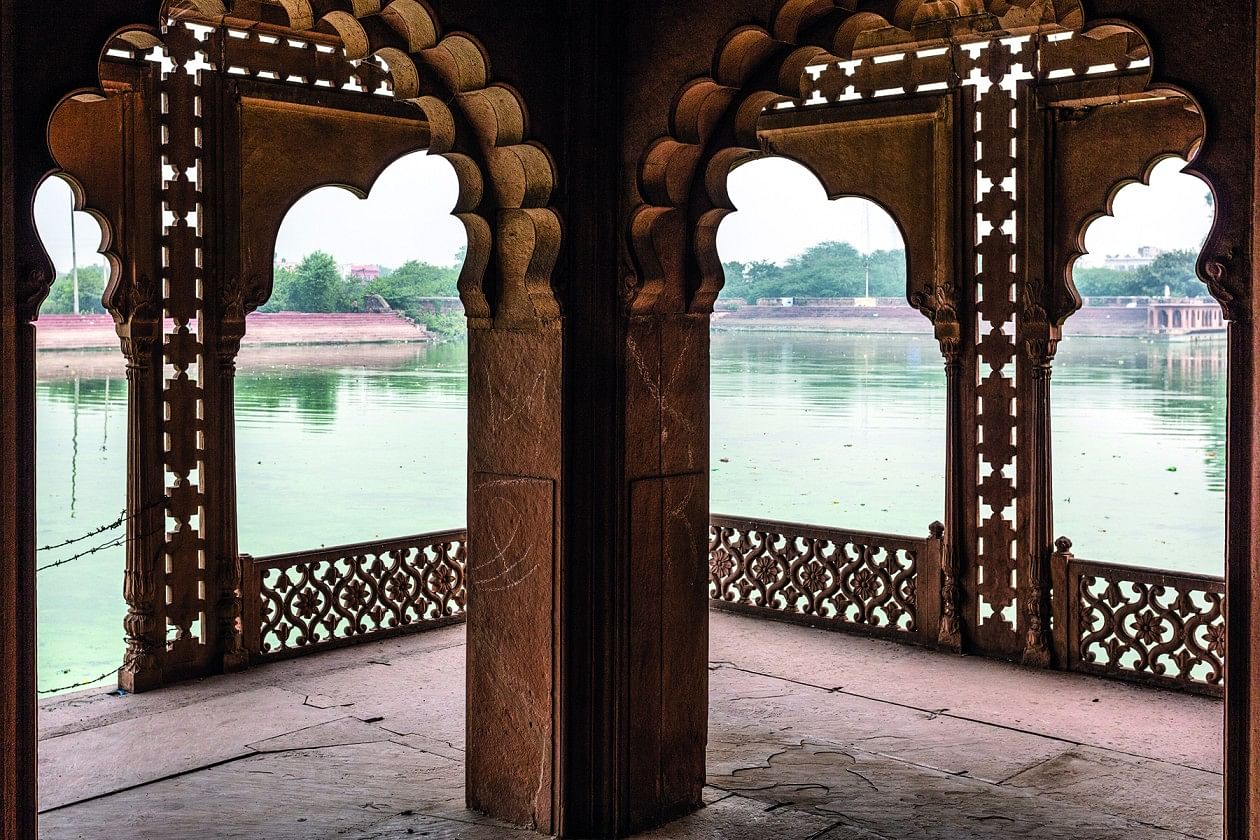

At Deeg, under Jat patronage in the Bharatpur region, a waterside pleasure palace is decorated with pierced walls and railings (figs 10, 11). Structures in and around the same site also incorporate earlier Mughal jalis in red sandstone, which stand out against the buff local materials. Later jalis are much less fine (figs 13, 14) but cheerfully present nevertheless in this site, which is an odd mix of architectural elements.

Also read: Overdressed, deluded—how Brahmins viewed Buddhists in medieval India

‘Jali mania’ is the spirit at nearby Bari where a whimsical sandstone jali bench (figs 15, 16) incorporates volutes and flowers and geometric interlace designed to amuse an imaginative patron. In another example of dogged devotion to jali designs, a dry and dusty Indian village landscape is seen through a long and lonely pierced wall at Chunar (fig. 17). Likely to be fairly modern, its kaleidoscopic designs are centred on floral heads and medallions and reflect the rich carving styles of the nearby historic Chunar fort.

Also read: Ashoka edicts silent on caste order. Runs counter to what we’re taught about varna history

This is an excerpt from “Jali Mania: From Rajputs to the Raj” in Jali: Lattice of Divine Light in Mughal Architecture by Navina Najat Haidar, published by Mapin Publishing, Ahmedabad. Images copyright, credit as listed under each image.

This is an excerpt from “Jali Mania: From Rajputs to the Raj” in Jali: Lattice of Divine Light in Mughal Architecture by Navina Najat Haidar, published by Mapin Publishing, Ahmedabad. Images copyright, credit as listed under each image.