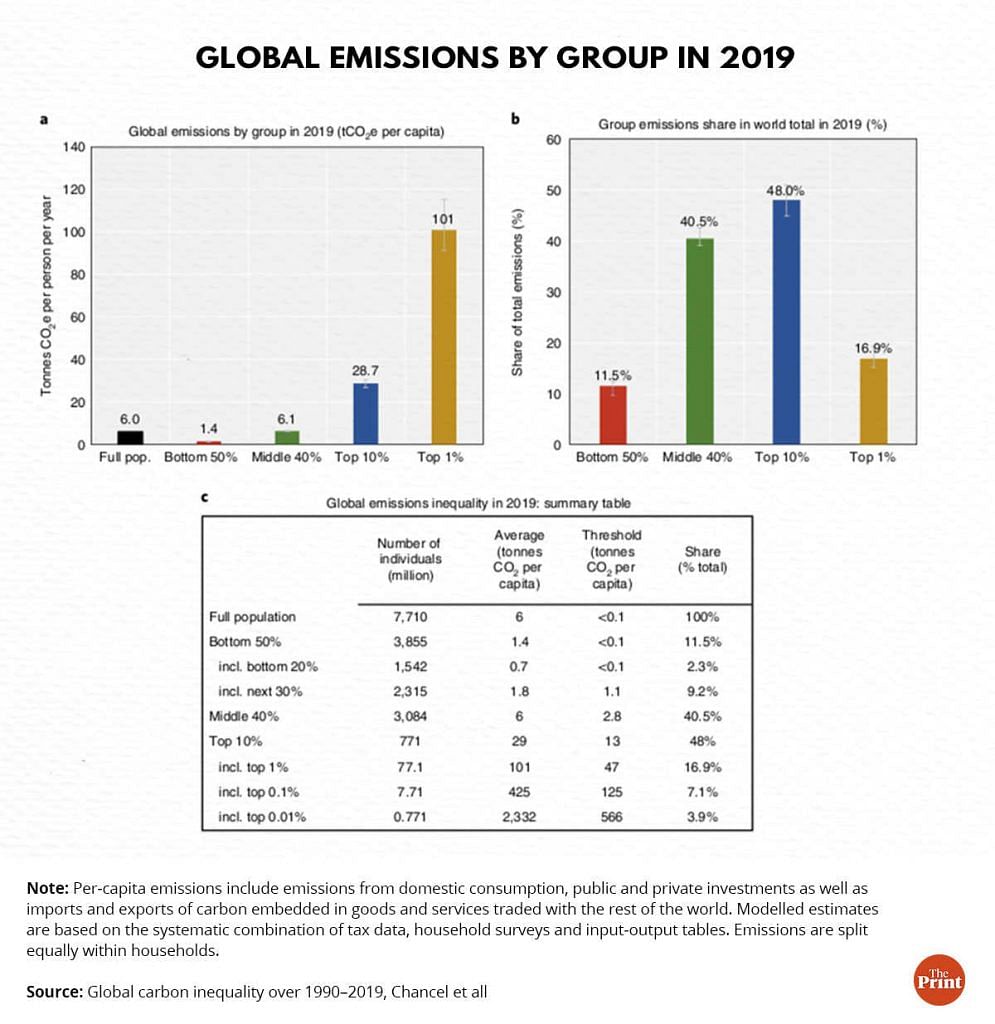

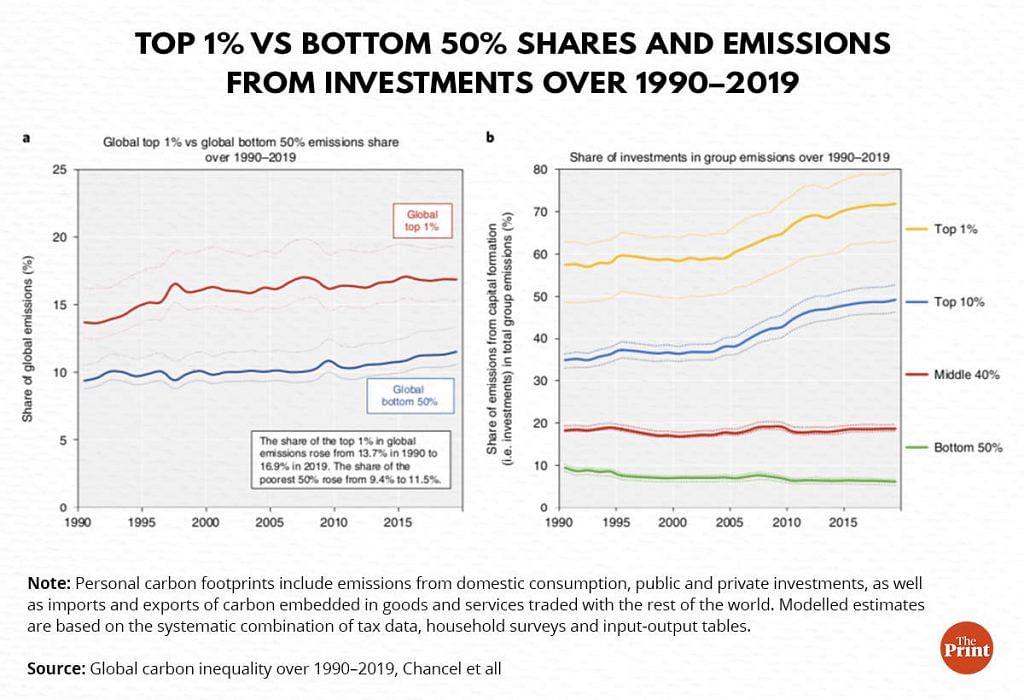

New Delhi: Just 10 per cent of the world’s population was responsible for 48 per cent of greenhouse gas emissions in 2019, a new study analysing carbon footprint estimates and income inequality has claimed. Further, it says, the top 1 per cent of emitters were responsible for nearly a quarter of the growth in carbon emissions between 1990 and 2019, while the bottom half caused merely 16 per cent.

Published in the journal Nature Sustainability last week, the paper titled ‘Global carbon inequality over 1990–2019’ was authored by French economist Lucas Chancel of the World Inequality Lab, Paris School of Economics.

Higher per capita emissions have been linked to higher amounts of wealth. Combining income/ wealth inequality data from the World Inequality Database with models of greenhouse gas footprints, it shows that while all humans contribute to climate change, they do not do so equally.

“Personal carbon footprints”, according to the study, include emissions from direct and indirect domestic consumption and financial investments, as well as government spending. It finds that “the bulk of the emissions generated by the global top 1% comes from their investments rather than their consumption”.

“Individuals can consume carbon, but they can also own [and invest in] firms that produce carbon,” Chancel told the climate-focused website Carbon Brief, adding that the paper “is proposing a method that is going to integrate these different bits of our carbon footprints together”.

However, when ThePrint asked Chancel about the role of investments in emissions, he cautioned: “I stress that these numbers should be interpreted with care given the lack of publicly available data on the issue and also because there are different ways people may want to follow to measure carbon footprints.”

Another key finding of the study is that while carbon inequality in the 1990s was driven predominantly by differences between countries, where “the average citizen of a rich country polluted unequivocally more than the rest of the world,” the situation has changed in the past few decades.

“Within-country emission inequalities now account for nearly two-thirds of global emissions inequality,” says the study, adding, “On top of the great international inequality in carbon emissions, there are also even greater emission inequalities between individuals within countries.”

The average global per capita emissions reached 6 tonnes of carbon-dioxide equivalent (tCO2e) in 2019. ‘Carbon-dioxide-equivalent’ is a standard unit for counting greenhouse gas emissions.

However, in order to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius by mid-century — as advised by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) — per capita emissions need to drop to 1.9 tonnes between now and 2050, and zero thereafter.

An annual per capita emission rate of 1.9 tonnes “is the equivalent of an economy-class round-trip flight between London and New York,” says the paper.

Scientists have warned that if global warming exceeds 2 degrees Celsius, the worsening effects of climate change will be irreversible.

Also read: 4.7% bump in GDP by 2036, 15 mn new jobs by 2047: Report on what net-zero can do for India

Carbon inequality between & within countries

The paper’s calculations account for greenhouse gas emissions due to private consumption, investments and government spending.

Its findings are not based on historical emissions (emissions since the industrial revolution), but emissions over the past three decades, from 1990 — when the first IPCC report came out — to just before the COVID-19 pandemic. These years “saw critical shifts in the distribution of world economic growth, which have not been systematically studied from the point of view of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions inequality,” the paper says.

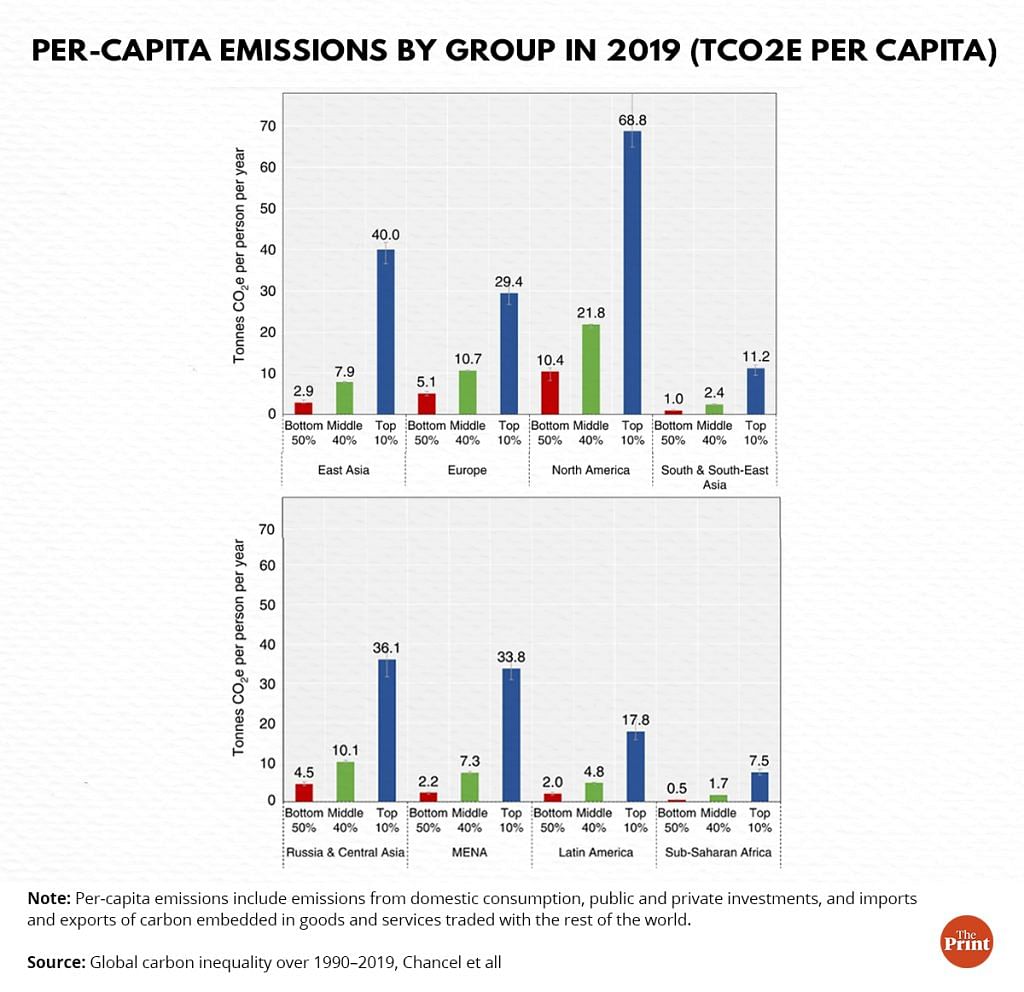

While North America and Europe are among the biggest contributors to global historical emissions responsible for global warming today, greater inequalities have emerged in the average per capita emissions within regions as well.

“Contrary to the situation in 1990, 63 per cent of the global inequality in individual emissions is now due to a gap between low and high emitters within countries rather than between countries,” the paper says.

In East Asia, the poorest 50 per cent emit on average 2.9 tonnes per annum, while the middle 40 per cent emit nearly 8 tonnes, and the top 10 per cent almost 40 tonnes, the study finds.

In North America, the bottom 50 per cent emit fewer than 10 tonnes, the middle 40 per cent around 22 tonnes and the top 10 per cent around 69 tonnes.

South and Southeast Asia have “notably lower” emissions than the other regions, the study says, with carbon emissions at around 1 tonne for the bottom 50 per cent and 11 tonnes on average for the top 10 per cent.

In India, the emissions of the bottom 90 per cent are “below the target”, the paper says, although the wealthiest 10 per cent “are already well above it”.

In India, the richest 10 per cent of the population will need to reduce 50 per cent of their emissions to fall in line with the Paris Agreement’s goals, the paper adds.

Targeting high emitters

Chancel hypothesises that national policies addressing climate change in North America and Europe have driven down national per capital emissions, but have done so disproportionately. According to the analysis in the paper, the emissions of the poorest 50 per cent in Europe and America dropped by 25-30 per cent between 1990 and 2019, while the top 10 per cent of emitters relatively unaffected, or even grew.

“Focussing on the specific issue of the carbon content of investments, it appears that progressive carbon tax systems could be helpful to accelerate decarbonisation,” the paper recommends.

It adds that another option is to make carbon tax rates increase with emission levels. “This could potentially be achieved via a combination of tax instruments, focussing on consumers as well as on investors in carbon-intensive activities.”

The paper comes ahead of the COP27, where negotiations on how to slow down climate change are likely to focus on global carbon inequalities. The COP will take place between 6-18 November in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

Also read: Between China, climate change & development, Ladakhi nomads are losing grip on their land