Chushul, Leh: As one drives along the stunning Pangong lake, the number of homestays and guesthouses that dot the route begin to thin past the village of Maan. By the time one reaches Chushul — a town in eastern Ladakh — the lake is hidden from view by hills, replaced by open fields.

In Ladakh’s arid, biting cold climate, these patches of green are vital for the survival of the Changpas, a high-altitude nomadic tribe indigenous to the Changthang region.

Chushul is only a few kilometers away from the Line of Actual Control (LAC) — the de facto border between India and China. This area has seen a lot of strategic action over the past few weeks, the latest being the disengagement of Indian and Chinese troops at Patrolling Point (PP) 15 in the Gogra-Hot Springs area, which has been a point of deadlock between both countries since the 2020 standoff.

Konchok Stanzin, councillor of Chushul and a member of the Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council, however, told ThePrint the disengagement agreement didn’t sit well with members of his constituency, for whom it could have life-altering consequences. Konchok held a press conference Monday to raise this issue. It was attended by people from the villages of Phograng and Maan.

“We have disengaged from PP 16 (Gogra) as well, a decades-long permanent post, which means crucial grazing areas like the Kugrang valley will become a buffer zone,” he told ThePrint.

“The nomads are extremely unhappy, because this means they lose access to that land. So much land has been lost across decades,” he added.

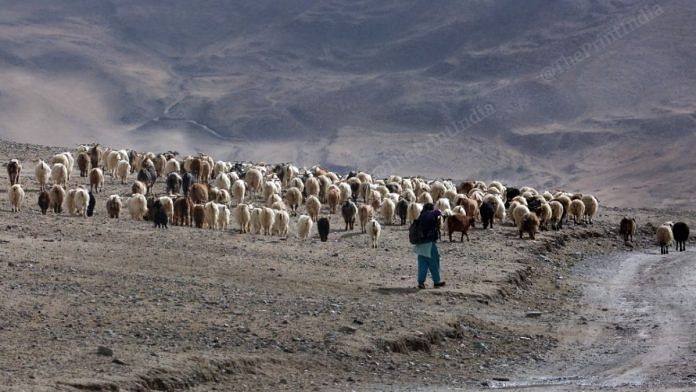

The Changpas travel from valley to valley grazing their flocks, a circular movement that is driven by the seasons. In the summer, they travel uphill where lush grass grows from snowmelt. In the winters — when temperatures freeze to below 30 degrees Celsius — they graze in the plains.

Pastures for Ladakhi nomads have been shrinking since 1962, when the Indo-China war broke out. Apart from simmering tensions with China, the slow burn of climate change, development, and changing demographics have slowly eroded the quality of these pastures, experts say.

“Before, all the families here were nomads. Now, it’s down to about 60 per cent. People are leaving to go to the city, or becoming labourers with the Border Roads Organisation (BRO) [a road construction force] because it is becoming unsustainable to graze. Something urgent needs to be done about this,” said Namgyal Phuntsog, a herder and former Chushul councillor who retired in 2015.

Also read: Kalbelia women won awards for folk dance but their quilt-making put food on table

Shrinking pastures

Konchok Ishey, leader of Chushul village, stood outside his home and pointed to the peaks, “Earlier, we used to go all the way to Rezang La and Black Top to graze our livestock, but now they won’t even let us come close to the base of these areas,” he said.

Ishey’s family used to own over 600 sheep and goats eight years ago. Today, they own just 280. Ishey attributes this dwindling of numbers to shrinking pastures.

“If things go on like this, we will have to consider selling our livestock and leaving pastoralism altogether. It’s a tight situation for us,” he said, adding, “Two or three houses in our village have completely stopped rearing livestock.”

The nomads of eastern Ladakh endure exceptionally difficult weather conditions to procure high-quality pashmina — fine goat hair which is processed and made into luxury shawls and other products. Research tracing the movements of Changpas in the Nyoma area show they travel around 135 kilometers through the year, moving from pasture to pasture, to feed their livestock.

Apart from tourism, the production of pashmina makes up a substantial revenue stream for the region. Ladakh produces about 50 tonnes of pashmina per year.

“The Changpas have, over centuries, tried and tested methods of adapting to this cold climate. They are constantly monitoring the quality and health of the pastures, and have found ways to cope with drought and locust attacks,” said Sunetro Ghosal, a researcher based in Leh who has worked with Changpas.

In the Chushul area, though, it’s not just the changing climate but also border tensions that have restricted nomadic movement.

According to councillor Stanzin, most winter grazing areas in Chushul have come under dispute after 2020. He argues that this makes it harder for grazers to maintain their animals, which are vulnerable in such extreme temperatures and could die without proper care.

“Us nomads know till how far our pasture lands stretch, and we know where to go for grazing. But when we go to one area, suddenly the army also follows to do its duty. We aren’t going across the border to make any trouble — we go, graze, and come back, which is our right,” said Phuntsog.

Last month, Chinese troops reportedly stopped Indian grazers from entering a pasture in Demchok, claiming the area was theirs. While the matter was resolved peacefully, grazers from Chushul told ThePrint that, in their experience, it was mostly the Indian Army that stopped them from accessing historical pastures.

“The movement of nomads becomes a point of negotiation for India. It’s important that the Army lets grazers go to the extent they used to. Nomads have been good allies to the government and the army. This land [now in the buffer zone] is absolutely vital,” said Stanzin.

A region in flux

The pastures that are left for grazing have been subject to both climatic and anthropogenic stresses in the recent decades. In the 1950s, an influx of Tibetan refugees — spurred by border tensions — settled across pastures in the Changthang region along with their livestock, further dividing the land. Research shows that between 1950 and 2006, the population of Chushul alone grew by 178 per cent.

“The influx of refugees and their livestock meant there was less area per animal to graze. This has also had an impact on wildlife since herbivores were in competition with livestock for pastures and grazing land,” said Yash Veer Bhatnagar, a scientist with the Nature Conservation Foundation, a non-governmental wildlife conservation and research organisation.

The Changthang region is a cold desert ecosystem home to several endangered species, such as the Himalayan wolf, snow leopards, and various ungulates like the kiang, or wild ass.

With the incentivisation of pashmina production, Bhatnagar and conservationist Tsewang Namgail found that since the 1980s, herders have preferred to keep pashmina goats, as opposed to the more traditional yaks and sheep.

According to Ghosal, this has resulted in the Changpas “renegotiating” their relationships with some of these wild species — such as the kiang — as pasture sizes shrink or are eroded.

Karma Tashi, a 66-year-old Changpa, who stopped grazing some years ago, said another looming threat was unpredictable weather patterns.

“During the war, the ice that formed was so thick, and the grass was very good quality. Over the years we have seen less ice, snowfall is not happening on time, and the pastures are getting over quickly,” he said.

Ladakh is dependent on snowmelt for its irrigation needs, but has lost at least 70.32 gigatonne of its glacier mass (along with Jammu and Kashmir). Ladakh’s largest glacier shrunk by 13.84 per cent from 1971 to 2017, a study from 2018 had found.

Its rocky terrain is not equipped to deal with much rainfall, but research shows precipitation has increased, causing more runoff and flooding.

Bhatnagar explained that when snowfall thins, the water melts away quickly and doesn’t percolate through the fields, affecting the flowering cycle of some plants in the region.

“If there’s no moisture through the summer months, and instead it arrives as rain in the monsoon months, the plants don’t have enough time to fruit, which can affect the composition of the pasture,” he said.

The warming climate has also allowed for something that wasn’t typical of the region: agriculture. Though most families farm to feed themselves, agriculture across eastern Ladakh has grown, partly because the climate now allows for it, Bhatnagar said.

Also read: Melting glaciers, water scarcity, exodus: How climate change reality is biting Ladakh villages

‘Need more inclusive development’

The Changpas from Chushul town ThePrint spoke to expressed a desire to see more development in the area. The central government announced a scheme called the “Vibrant Villages Programme” during this year’s Budget, which, similar to the Border Area Development Programme (BADP), will focus on building projects “related to village infrastructure like roads and bridges, health, education, agriculture, sports, drinking water and sanitation.”

Kumbai Nyoma, a Changpa with a flock of 200 sheep, yaks, and goats, gives the example of a pre-fabricated hut built by the government — a sturdier structure compared to the tents made of yak wool which Changpas have typically inhabited — in a winter pasture where he grazes his animals. The nomads venturing far in winters use the hut for shelter.

“This tent is waterproof, it’s a little warmer in the winters. I would like it if the government brought more of them,” he said.

More development and tourism mean the lifestyles and culture of the Changpas will likely transform to become more sedentary. Tsering Tondop left pastoralism three years ago and is dependent on his six children — four are with the Indian Army, one is a driver, and the sixth lives at home.

“The mortality rate of my animals was very high because of reduced grazing land,” he said, adding that his children didn’t want to live the nomadic life. “They wanted steady jobs, so they left.”

According to councilor Stanzin, migration to the city of Leh can be helped if there are incentives for nomads to stay, such as an income guarantee or better basic infrastructure.

Ghosal, too, believes that policies should be more geared to the needs of nomads.

“A lot of policies don’t adequately take into account the nomadic lifestyle. Some years ago, a dehairing plant for raw pashmina had been set up all the way in Leh, with no consideration to the fact that the nomads will have to bear the expense to travel there,” said Ghosal. “It’s a challenge, but policies dealing with nomads, whose lives are in flux, should be more inclusive of their voices and needs.”

(Edited by Zinnia Ray Chaudhuri)

Also read: After ‘freak accident’, it’s full steam ahead for India’s 1st geothermal power project in Ladakh