Rome: India stands at the threshold of reaping its demographic dividend, yet a significant portion of its working-age population remains employed in the non-productive agricultural sector, claims the latest report prepared jointly by the International Labour Organization (ILO) — United Nations body on labour rights and issues — and Institute of Human Development, a Delhi-based labour policy think tank.

The ILO’s India Employment Report 2024, released Wednesday, uses statistics published by the Government of India and the Reserve Bank of India through the surveys conducted from 2000 to 2022. For the years 2000 and 2012, the report uses the National Sample Survey rounds on employment and for 2019 and 2022 it uses the Periodic Labour Force Participation Surveys.

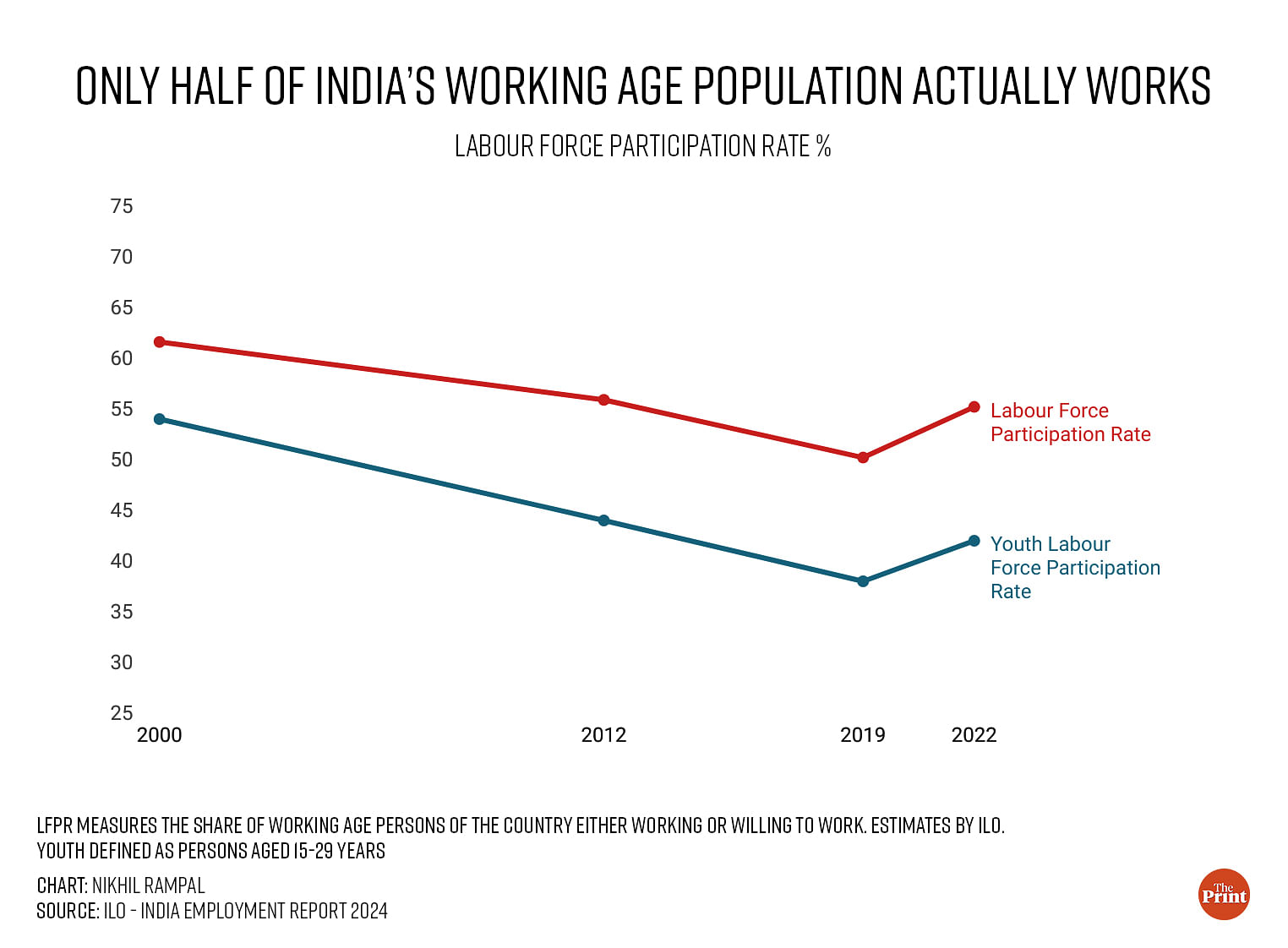

Across the world, the Labour Force Participation Rate (LFPR) in 2022 was 59.8, but in India, it was 55.2 percent in 2022 — 0.7 percentage points less than in 2012, when it stood at 55.9 percent.

The LFPR is the proportion of the working-age population either working or seeking work.

The report clarifies it is unlikely that this reduction in LFPR is due to the Covid-19 pandemic since the major fall in participation rates happened in 2019 when the LFPR dropped to 50.2 percent from 55.9 percent in 2012.

This means that only a little more than half of India’s young working-age population is actually working or seeking work.

Moreover, the report adds that India’s high economic growth has not resulted in the growth of jobs. “Despite the reasonably high growth, there has not been commensurate expansion in productive employment opportunities. Instead, there has been falling employment intensity in the growth process,” it says.

“It is widely acknowledged that this has been mainly due to the growth process being services-led, contrary to manufacturing-led, that most developed countries experienced during their development process. Consequently, the process of structural transformation has been slow in India and even characterised as ‘stunted’,” the report adds.

Also Read: Here are 5 key takeaways from Household Consumption Expenditure Survey 2022-2023 highlights

Questions on low unemployment

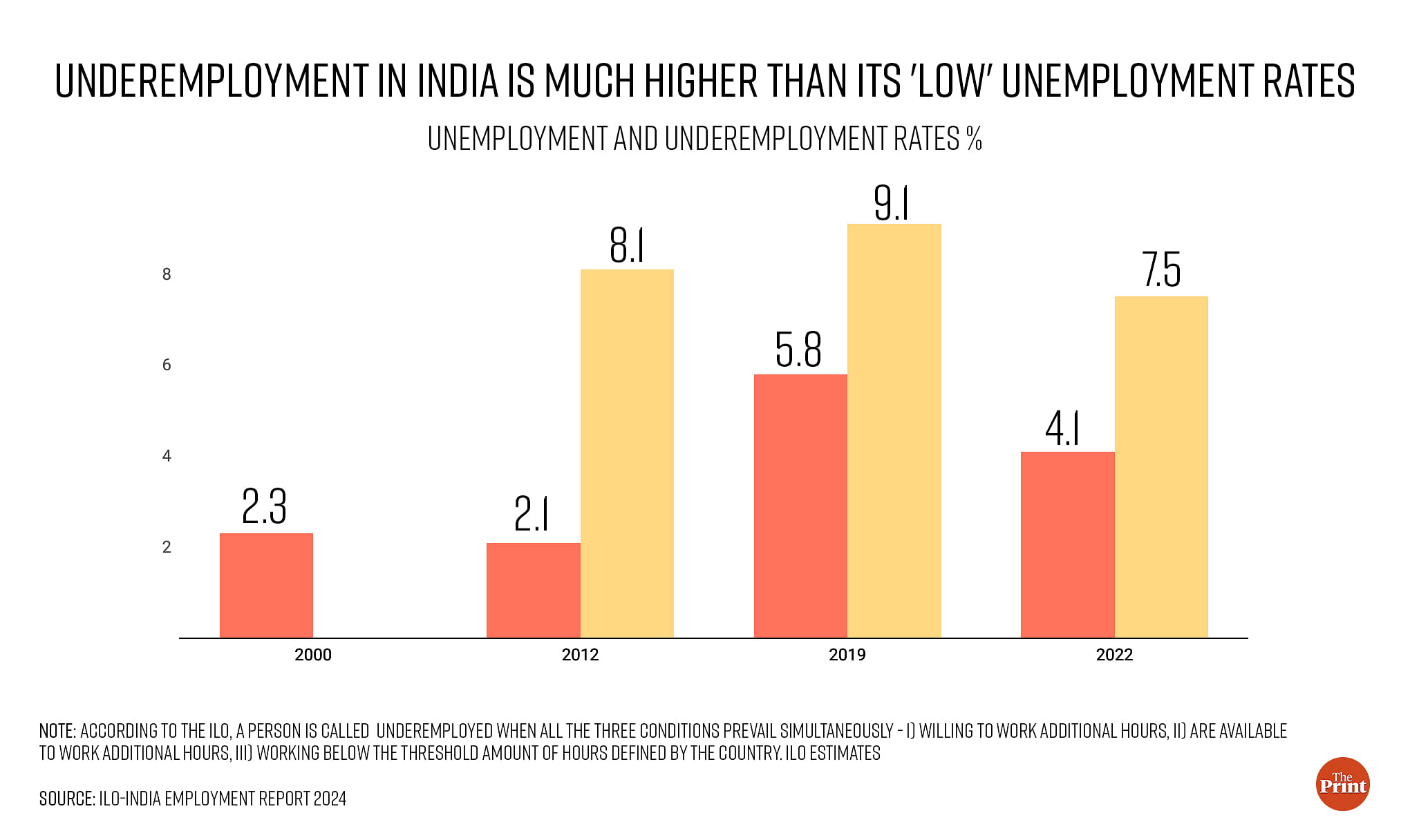

According to the report, India has a relatively low unemployment rate of less than 5 percent (about 4.1 percent in 2022 against 5.8 percent in 2019). This is up from the 2 percent unemployment rates the country faced in 2000 and 2012.

However, the ILO acknowledges that for a developing country like India, low open unemployment — a situation where individuals are actively seeking but unable to find work — isn’t a good metric because people cannot stay unemployed for long.

The report instead introduces the metric of “underemployment” — a condition in which those willing to work are ready to work extra hours and are working below a threshold level of time defined.

The report shows that India has a high underemployment of labour — meaning those working are not working up to their full capacity. The underemployment rate in India was 8.1 percent in 2012 and 9 percent in 2019, which fell to 7.5 percent in 2022.

However, even the report admits that this fall should not be taken at face value, as it could also imply a shortage of work opportunities, especially for women.

“The increase in underemployment in the pre-pandemic period and the decline in underemployment during the pandemic and post-pandemic periods, especially among women, raise questions about the availability of additional employment opportunities,” the report highlights.

It also mentions that in the past 10 years, output production in India has become more capital-intensive, which increasingly rules out jobs for low-skilled workers.

“Due to increasing mechanisation and capital use, the employment generation in India has become more and more capital-intensive, with fewer workers employed between 2000 and 2019 than in the 1990s,” it notes. “The skill intensity of employment in industry and services increased during this period, which was contrary to the labour market needs of the country.”

Squandering demographic dividend

According to the ILO report, India seems to be missing out on reaping the bulk of its demographic dividend, with youth participation at work falling despite more youngsters added to the workforce in the past two decades.

The report states that India’s working-age population (age 15-59) has increased from 59 percent in 2011 to about 63 percent in 2022, however, fewer youngsters are working.

The report cites that the youth labour force participation rate (LFPR) was 54 percent in 2000, which dropped to 42 percent by 2021.

The “youth” category refers to people aged between 15 and 29. The numbers indicate that there has been a sharper fall in the number of people in this age group than in the age groups of 20-24 and 25-29, implying India’s population is ageing.

“A large proportion of the population is of working age, and India is expected to be in the potential demographic dividend zone for at least another decade,” says the report.

“But the country is at an inflexion (sic) point because the youth population, at 27 percent of the total population in 2021, is expected to decline to 23 percent by 2036,” it highlights.

Agriculture still absorbs majority labour force

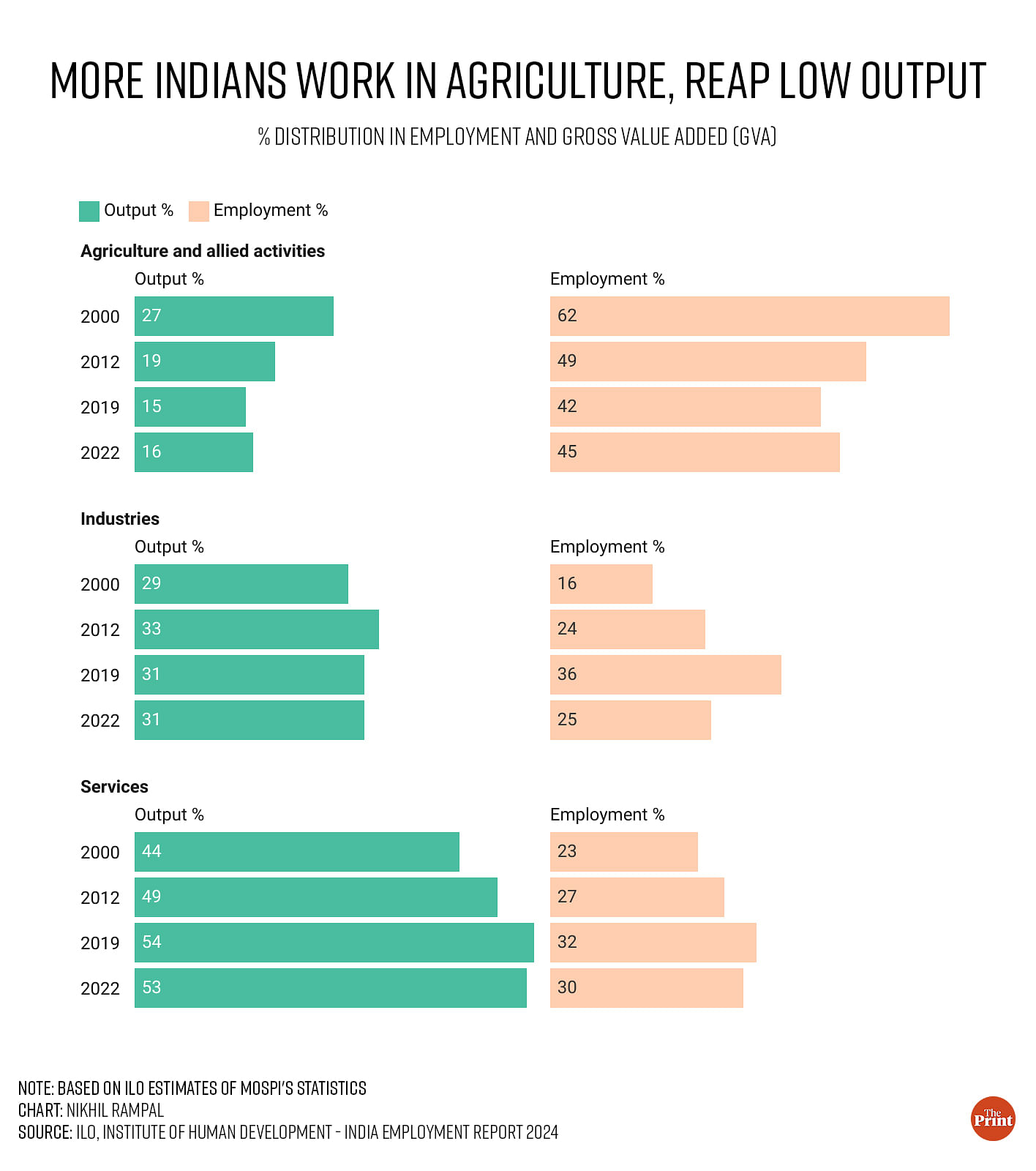

One of the major highlights of the report is that India’s employment generation under Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s second term hasn’t taken place as much in its productive sectors — industries and services — as it has in low-productivity agriculture.

From 2000 to 2012, the share of people employed in the agricultural sector declined marginally, but after Covid-19, there has been a surge in employment in agriculture.

During 2019-2022, the labour force of India aged 15 and above has grown at an annual growth rate of 4.62 percent. During this period, the share of people employed in agriculture has increased by 8.93 percent, followed by construction, 6.37 percent; manufacturing, 3 percent; and services, 1 percent.

The report also mentions that from 2000 to 2012, India’s non-agricultural employment rose by 3.86 percentage points. This was 2.09 and 2.61 percentage points between 2012-2019 and 2019-2022, respectively.

At the same time, the share of the population employed in agriculture in 2022 remains huge — 45 percent of India’s labour force is producing just 16 percent of the total GDP, which is the agriculture sector’s contribution.

Notably, India’s share of employment from agriculture has declined from 62 percent in 2000 to 45 percent by 2022 — but it still is significantly large.

The services sector, which employs about 30 percent of the labour force, produces 53 percent of India’s GDP in 2022. The share of labour employed in industries was 16 percent in 2000, which grew to 25 percent by 2022.

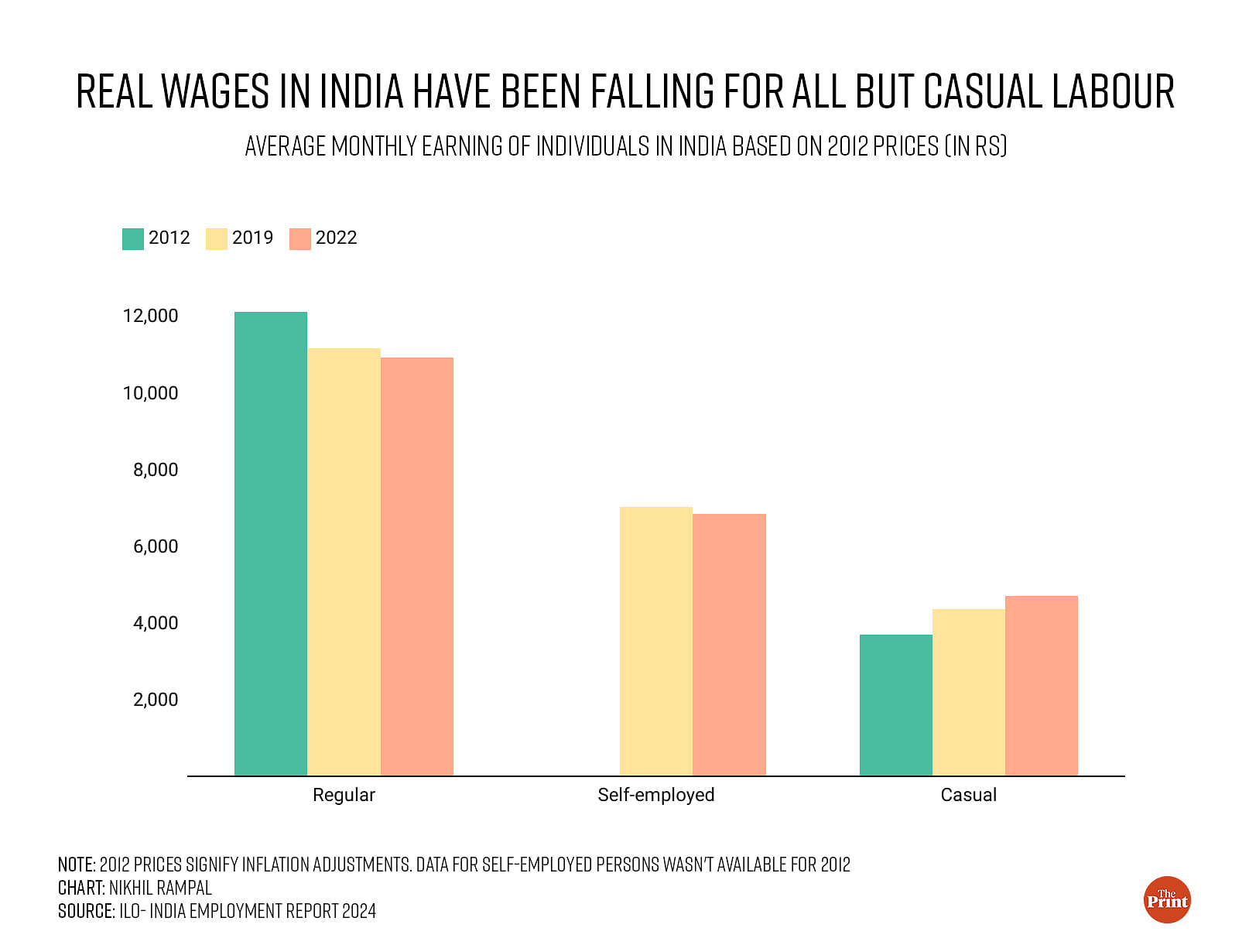

Few salary earners, declining wages

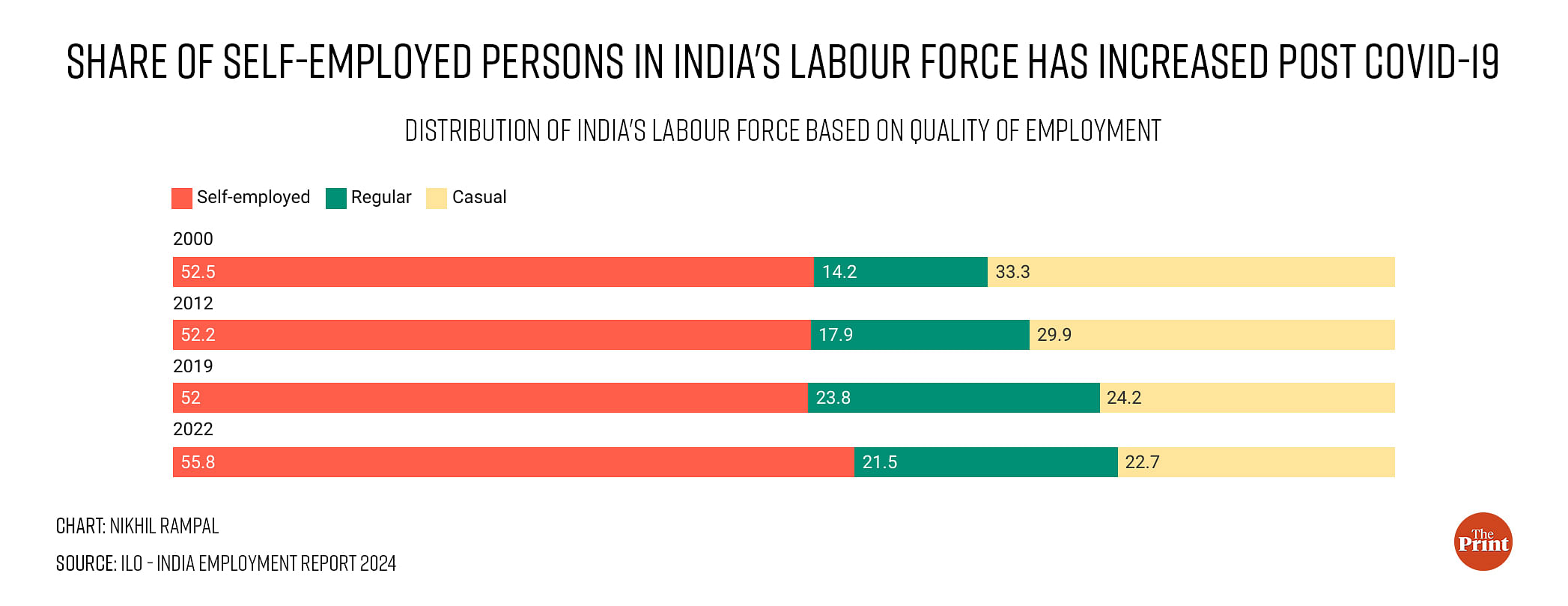

Another key highlight of the report is that India’s labour force is mostly self-employed. A low share of the workforce works in a regular salaried job.

In 2022, nearly 55 percent of the workforce were self-employed, about 22.7 percent were engaged in casual labour and only 21.5 percent were employed in a regular salaried job.

This is particularly noteworthy because self-employed jobs in India, according to the data, are typically low-paying.

In 2022, a person on a regular salary earned Rs 19,000 a month, while a self-employed one on average earned Rs 11,973. The situation was worse in casual labour, where the average monthly earnings were Rs 8,267.

Nikhil Rampal is a visiting fellow of the CVoter Research Foundation. He could be found on X (formerly Twitter @NikhilRampal1)

(Edited by Richa Mishra)