A heady era has lulled investors into believing that India’s omnipotent PM determines India’s economic destiny. But things may be about to change.

Over the last couple of years, we Indians have had our cake and eaten it too; i.e. we have been able to combine falling GDP growth (and the falling interest rates and low inflation that come with it) with strong FII inflows which have funded our Current Account Deficit and thus kept the INR stable.

This heady era has lulled some investors into believing that we have entered a new construct where India’s omnipotent PM determines India’s economic destiny. If commodity prices continue rising and/or India’s budget deficit rises, this aura of Indian invincibility will be challenged courtesy rising inflation and falling real interest rates which would trigger FII outflows.

“The Greenspan put was a caustic encapsulation of the belief that the Fed, under Alan Greenspan, its longtime chairman, would always bail stock investors out of their losing positions. That was obviously ludicrous. But it contained an important, and useful, grain of truth. If the Fed could, and would, always act to prevent economic catastrophe, which imparted option value to equity valuation.” – The Economist (August 11, 2011)

A reactive government….

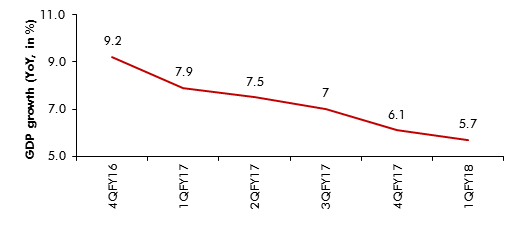

Since the Jan-March 2016 quarter, GDP growth in India has fallen continuously. As of 1QFY18, growth fell to 5.7 per cent (see exhibit below). This has led to mounting discontent evidenced by the 27 September 2017 piece by former NDA Finance Minister Yashwant Sinha in the Indian Express where he says (click here):

“Private investment has shrunk as never before in two decades, industrial production has all but collapsed, agriculture is in distress, construction industry, a big employer of the work force, is in the doldrums, the rest of the service sector is also in the slow lane, exports have dwindled, sector after sector of the economy is in distress, demonetisation has proved to be an unmitigated economic disaster, a badly conceived and poorly implemented GST has played havoc with businesses and sunk many of them and countless millions have lost their jobs with hardly any new opportunities coming the way of the new entrants to the labour market…”

Exhibit 1: GDP growth in Indian has been declining for six consecutive quarters

Given the government’s response in expediting action on policy concerns in the wake of falling economic growth, it would not be unfair to say that the NDA is a reactive administration. The fact that the government faces 14 elections in the next 17 months makes it that much more sensitive to comments on its economic performance.

Exhibit 2: In the last six months a series of measures have been taken by the government to revive the economy

| S.No. | Details | Link | Date |

| 1 | Karnataka, Maharashtra, Punjab, Uttar Pradesh and more recently Rajasthan are some of the states that have announced farm loan waivers. The total cost of these loan waivers is ~Rs1.05tn ($16bn or 0.7 per cent of GDP). | https://goo.gl/qZpyfH

|

April – Sep 2017 |

| 2 | The GST council lowered rates on 27 products and few services and eased rules for SMEs and exporters | https://goo.gl/Tfn3Lm | 07-Oct-17 |

| 3 | The government increased the minimum support price (MSP) of wheat by Rs110 (or 7 per cent) a quintal. This is the highest MSP hike in six years. The MSP for gram or chickpeas was raised by 10 per cent while for mustard was raised by 8 per cent. | https://goo.gl/A3trsh | 25-Oct-17 |

| 4 | The government approved a public sector bank recapitalization plan of Rs2.11tn rupees (US$32.6bn) over the next two years, in a bid to clean public sector banks’ books and revive investment in a slowing economy. | https://goo.gl/q3uXaz | 24-Oct-17 |

| 5 | The government announced an outlay of Rs6.92tn (US$107bn) for building an 83,677km road network over the next five years. This includes the Bharatmala Pariyojana with a Rs5.35tn (US$82bn) investment to construct 34,800 kilometres of roads. In addition, Rs1.57tn (US$24bn) will be spent on the construction of 48,877km of roads by the state-run National Highway Authority of India (NHAI) and the ministry of road transport and highways. | https://goo.gl/GdowWC | 24-Oct-17 |

Source: News articles, Ambit Capital research.

Is there a Modi put?

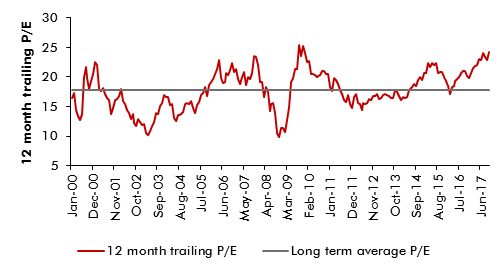

The above pattern of events is leading investors to believe that there is a Modi put in play; i.e. when GDP growth slows down, the NDA will go into overdrive mode to reflate the economy. Given India’s sliding economic growth and weak EPS growth (Sensex EPS growth has been in single digits for the last four years and seems likely to be in single digits in FY18 as well), the Modi put is as good an explanation as any for the Sensex’s surreal valuation of 24x trailing earnings.

Exhibit 3: The Sensex’s 12 month trailing P/E is nearly approximately 2 standard deviations above the mean

The sequence of events which has transpired in India over the past couple of years is reminiscent of what happened in America in the decade running up to the Lehman crisis when the US markets believed that there was a Greenspan put in play; i.e. whenever it looked as if the US markets were facing a challenge (e.g. the LTCM crisis in 1998, the aftermath of 9/11), Greenspan would come to the rescue with monetary easing. These interventions by the Fed emboldened investors to take increasingly risky long bets in the US stock and bond markets until that party ended in 2008. So is India heading down the same road? In specific, can Mr Modi underwrite returns for equity investors?

The challenge: The trilemma

Macroeconomic theory says that it is impossible for an economy to have all three of the following the same time:

- A fixed foreign exchange rate;

- Free capital movement; and

- Independent monetary policy.

China is an example of a country that has fixed the value of its currency and also has an independent monetary policy, but cannot allow capital to flow freely across its borders by consequence. Italy is an example of a country that has its exchange rate effectively fixed (thanks to the Euro) coupled with free flow of capital but its monetary policy cannot be independent (effectively the European Central Bank runs monetary policy for Italy and all the other Eurozone countries).

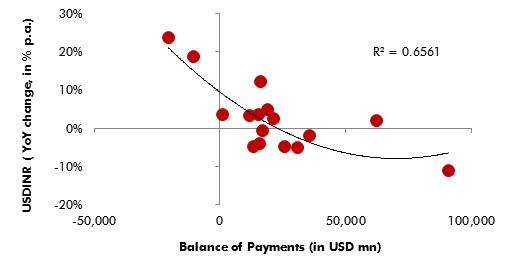

In India’s case, if the RBI wants to keep the INR at around the Rs65/US$ mark and if the country wants to continue to have free capital movement then the RBI has to reconcile itself to losing control of monetary policy. In the current context that means that were economic growth to stay weak, it is unlikely that the RBI can support a recovery through rate cuts given that India’s current account deficit is running at around 2 per cent of GDP. Hence, India needs capital inflows of around 2 per cent of GDP to keep the INR stable. Such capital inflows become less likely were the RBI to cut rates meaningfully at a time when the Western central banks are hiking their policy rates.

Exhibit 4: The INR depreciates when Balance of Payments (current + capital account) is negative

In fact, where things could get tricky for India – and where the trilemma could come to the fore – is if:

(a) Global commodity prices keep rising:

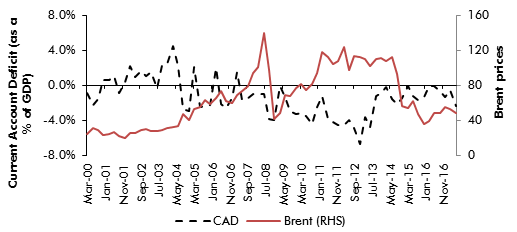

Crude petroleum, petroleum gas, and copper are two of India’s largest imports.

They account for around 37 per cent of India’s import of goods. While the price of oil has risen by 13 per cent per annum from $47.62 a barrel (as of 30 October 2015) to $60.94 a barrel (as of 31 October 2017), copper has risen 16 per cent per annum from $5112 per metric tonne (as of 30 October 2015) to $6839 per metric tonne (as of 31 October 2017) in the past two years. This has had a direct impact on the current account deficit, which has widened (see exhibit below). If this trend continues, India will have a problem on its hands as the RBI might have to tighten monetary policy even with a weak economic backdrop in India.

Exhibit 5: Rising oil prices worsen India’s current account deficit as evinced by the episode spanning CY09-CY13 and the CY07 episode

(b) Inflation rises:

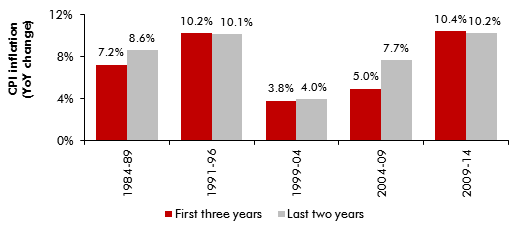

Inflation in India usually picks up in the run-up to General Elections. In specific, a historical analysis of inflation cycles in India suggests that average inflation tends to be higher in the last two years leading up to a General Election (GE). For instance, average CPI inflation was higher by 80bps in the last two years leading up to a GE in the case of the last 5 election cycles (see exhibit below, for more please see our note dated 27 July 2016 titled “The potent political underpinnings of inflation in India”)

Exhibit 6: In the case of the last 5 election cycles, average CPI inflation was higher by 80bps in the two years leading up to a General Election

Such a rise in CPI inflation would not only forestall further rate cuts from the RBI, it would also push up bond yields and thus increase the cost of capital (against the backdrop of a sluggish economy). Since inflation erodes the value of the currency, rising inflation would also trigger capital outflows thus putting pressure on the INR.

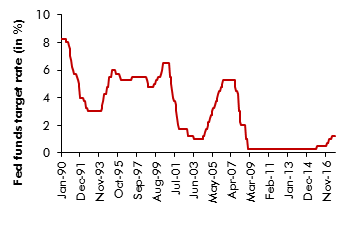

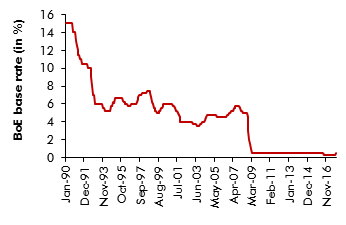

(c) Global liquidity tightening:

The Fed has hiked rates three times since late 2016 and seems all set to hike once more before the end of 2017. On November 3 2017, the Bank of England raised rates for the first time in a decade by a quarter of a percentage point to 0.5 per cent. However, the ECB and the Bank of Japan have still not tightened monetary policy. Hence, liquidity continues to slosh around the global financial system.

Exhibit 7: The Fed has been hiking rates over the past one year…

Exhibit 8: ..while the Bank of England hiked for the first time in ten years on 2 November 2017

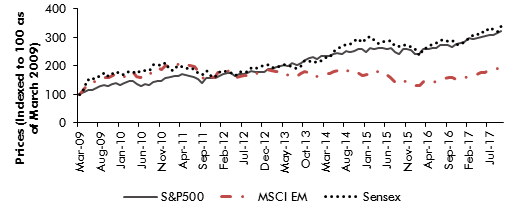

Concerted tightening of monetary policy by the Western central banks would bring to an end the post-Lehman era of almost free money sloshing around the world, which has resulted in the S&P500, MSCI EM, and the Sensex hitting record highs in spite of fairly ordinary underlying economic performance (see exhibit below).

Exhibit 9: S&P500 (16 per cent CAGR in $ terms), MSCI EM (9 per cent CAGR in $ terms), and the Sensex (17 per cent CAGR in INR terms) have given stellar returns since 1 March 2009

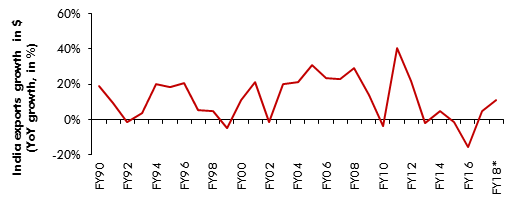

As this era of central bank liquidity gradually winds down in 2018, EMs including India will have to answer tricky questions regarding Balance of Payments, especially since in India’s case export growth has weakened over the past 4 years (in spite of the Western economies recovering and in spite of Asian economies like Bangladesh and Vietnam showing consistently high levels of export growth, see exhibit below).

Exhibit 10: Export growth has conked off in India

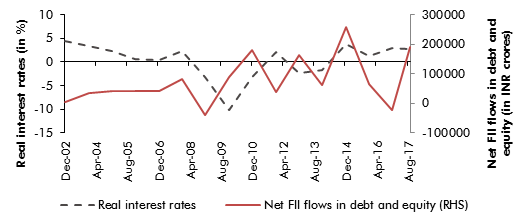

If the Indian economy is not able to get export growth firing again, then global liquidity tightening and/or rising commodity prices would compel the RBI to tighten monetary policy (even as Indian GDP growth stays weak). Such a move by the RBI should shore up FII inflows (which seem to track real interest rates) but would exert further pain on a sluggish economy.

Exhibit 11: Real interest* has been rising, driving capital flows

Investment implications

The illusion that the Indian government holds the country’s destiny entirely in its own hands has been facilitated by a combination of circumstances. Some of these circumstances, to the NDA government’s credit, are of its own making; e.g. fiscal rectitude in all of the budgets that this government has presented so far and an attack on black money.

However, India has also benefited enormously from benign oil prices alongside the liquidity generated by Western central banks. This has allowed us Indians to have our cake (in the form of consistent inflows of foreign capital in our financial system) and eat it too (in the form of low CPI inflation and low interest rates). This divine combination – of capital inflows into India alongside low Indian interest rates – cannot sustain indefinitely.

As the Western economies recover, not only are commodity prices likely to rise globally but also foreign capital inflows into India could slow down. Alongside this, if the NDA were to let its fiscal rectitude slip in a bid to win more elections over the next 17 months, then the outlook for the market could change very quickly.

Saurabh Mukherjea is the CEO of Ambit Capital Pvt. Ltd.

This analysis originally appears in ‘The Sceptical CEO’ section of the Ambit website.

So, Dooms day is not far off?

What is the way out?