New Delhi: The year was 1953. A tall, handsome man with a short, twirled moustache and “a clipped South Asian accent” barged into US Assistant Secretary of State Henry Byroade’s room. “For Christ’s sake, I did not come to the United States to look at barracks,” he entreated him. “Our army can be your army if you want us. But let’s make a decision soon!”

The man was Pakistan’s General Ayub Khan. His demeanour, the Americans felt, was charming and his ask for military aid, desperate. The then Secretary of State, John Foster Dulles, who famously called India’s neutral foreign policy “immoral”, assured the restless General that the aid would surely come. Only a formal agreement could take some time.

Later the same year, a report in The New York Times said the American president, Dwight Eisenhower, was indeed in favour of a defence deal with the Pakistanis. The report quoted an anonymous source as saying “the time has come to put an end to Washington’s patience with (then Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal) Nehru. The US should take a firmer course with Nehru, who has often embarrassed the US.”

Writing about the incident decades later in the introduction to the book India and the United States: Estranged Democracies 1941-1991, published in the early 1990s, late US Senator Daniel Moynihan said the anonymous source quoted in the piece was presumably Richard Nixon, then US Vice President.

By 1954, a defence treaty was signed between the US and Pakistan. Anticipating the Indian anger, Eisenhower wrote Nehru a letter to allay his concerns. US weapons to Pakistan were solely for the purpose of thwarting the communist expansion, he said. They would never be used against India.

As the then US ambassador handed over the letter to Nehru, the Indian PM smiled understatedly, and looked at his cigarette for a few seconds. It was not the US intentions that troubled him, but the consequences of this action, writes author Dennis Kux in Estranged Democracies.

In India, where foreign policy was hardly a matter of public concern, there was a loud outcry.

As Moynihan wrote, “For most Indians, differences over the containment policy and nonalignment involved abstract concepts that were of interest mainly to the educated elite. Anything touching on the relationship with Pakistan, however, just seven years after the trauma of partition, was a different matter, striking a deeply emotional nerve throughout the Indian body politic.”

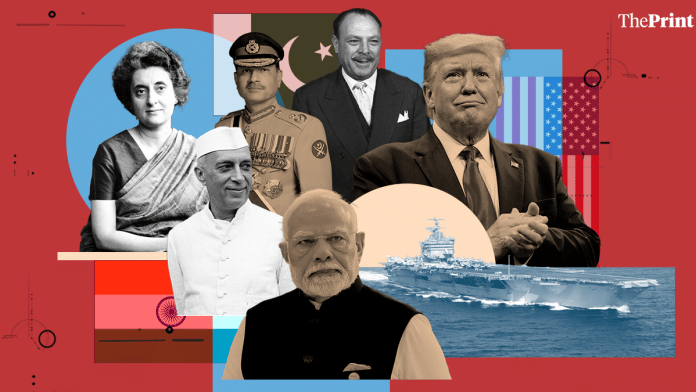

More than 70 years and many moments of hard-earned reconciliation later, the story of the “estranged democracies” has seemingly reached a near-identical point. Upset with India for buying and processing oil from Russia, and not providing adequate market access to the US, the Trump administration has slapped 50 percent tariffs on Indian goods.

To add to that, much to the chagrin of common Indians, the US administration has been investing deeply in its relationship with Pakistan. General Asim Munir’s recent visits to the US, including a luncheon meeting with President Donald Trump just weeks after India and Pakistan emerged from a short yet intense aerial conflict, has been emphatically noted by not just foreign policy observers, but the Indian public at large.

Writing about the tense relationship between the two largest democracies of the world in 1993, Moynihan had said “estrangement is the natural side of this relationship”.

In the three decades that followed, especially after the two countries signed the historic 123 Agreement in 2008, this perception had been adequately, if not wholly, upended. But years later, going by the recent spate of events which has seen India-US relations reach their nadir, the perception has made a decisive comeback.

As former minister of external affairs Salman Khurshid tells ThePrint, “Indians have always been sceptical of the US, and the US has always given good reason for this scepticism… they have always said ‘this is the line, follow it,’ and India has refused to do that because its self-esteem has not allowed it.”

How accurate is this sentiment? What are the factors that have shaped Indian scepticism towards the US for the last eight decades, especially before the Cold War ended? Has the US really taken India for a ride, as many commentators believe? Or is there, as a prominent foreign policy strategist told ThePrint, “an in-built bias against the Americans” among Indian elites? ThePrint traces this long history of “estrangement”.

Also Read: For Indian Mercedes, Asim Munir’s dumper truck in mirror is closer than it appears

Early seeds of scepticism

Nehru’s immediate response to Eisenhower’s letter had hardly betrayed the extent of his anger. Just weeks later, in April 1954, he wrote a letter to Indian chief ministers saying India should discourage largescale exchange of people between the two countries.

“It is not desirable for us to send out students or others to the US for training, except for some very specialised courses,” he said.

In a memorandum issued the same year, he wrote, “I dislike more and more this business of exchange of persons between America and India. The fewer persons that go from India to America or that come from the US to India, the better.”

As Byroade wrote of the consequences of the US’s defence deal with Pakistan many years later, “We knew they (India and Pakistan) disliked each other. We misjudged the intensity of their feelings.”

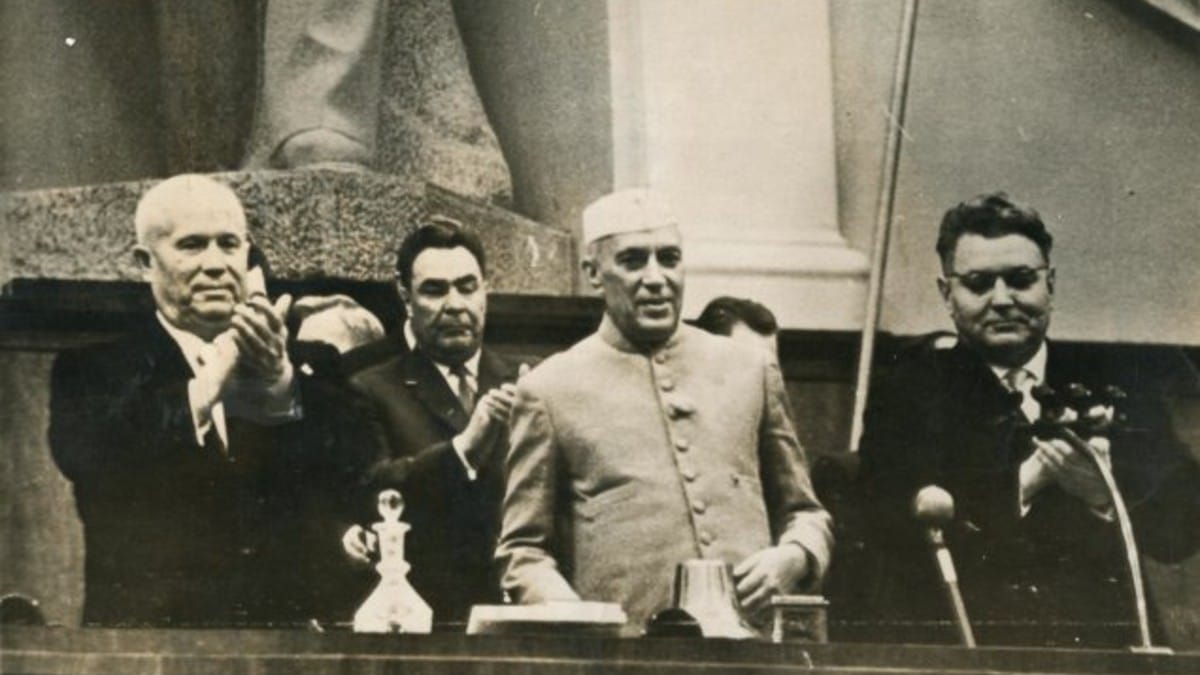

The year after the US-Pakistan deal, Nehru was off to the Soviet Union, addressing its people on state television—the first non-communist leader to do so. Months later, Communist Party First Secretary Nikita Khrushchev and Premier Nikolai Bulganin came to India. They officially dropped the Soviet policy of neutrality on Kashmir, and said Kashmiris have already expressed their desire to be a part of India, and no plebiscite was therefore needed.

For all practical purposes, the die was cast. India and Pakistan’s rivalry now had clear poles on the international stage—if Pakistan had the US, India had its own superpower ally. The most immediate benefit for India was a veto in its favour at the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) on the question of Kashmir.

India’s foreign policy under Nehru was already showing signs of steering away from his carefully crafted non-alignment.

In some ways, the Indian elite’s scepticism of the US, which was refracted through the prism of the British, predated the country’s independence in 1947. Many educated Indians saw the US as a “den of materialism and crime”. Nehru himself, in as early as 1928, wrote that “it is the United States which offers us the best field for the study of economic imperialism”.

But in the Second World War, the US was arguably the most important country to repeatedly prod the UK to end its colonial empire in India, thereby changing Indian attitudes towards the US.

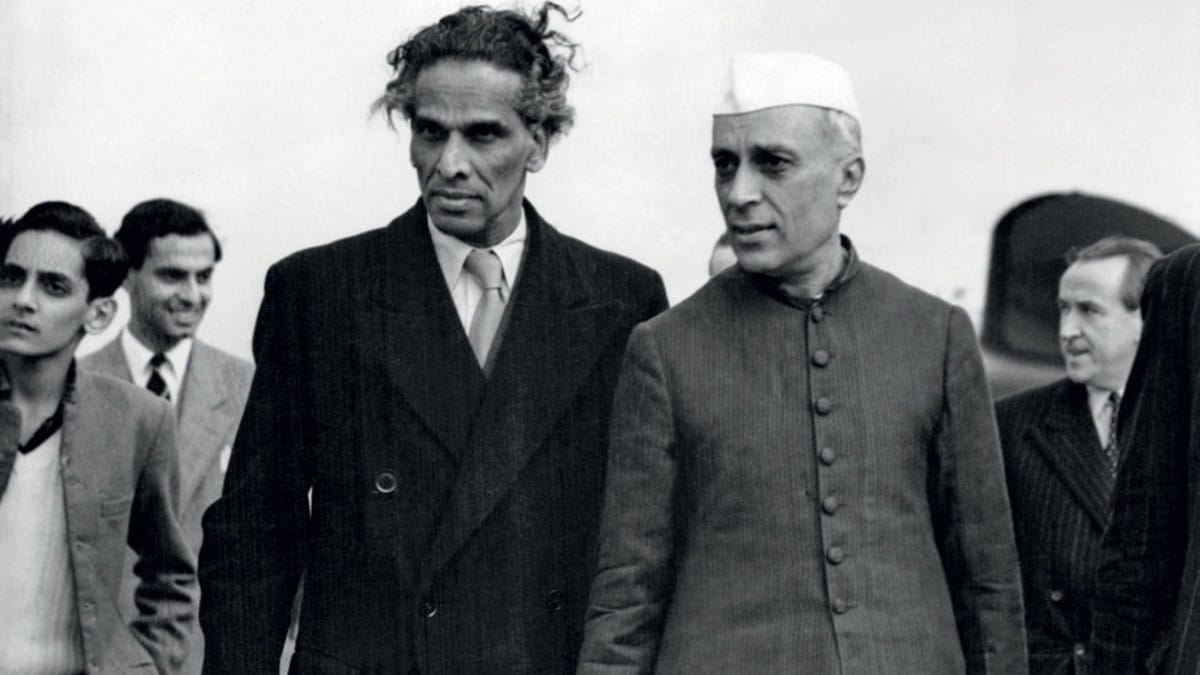

Post-Independence, Nehru, who himself was deeply aligned culturally with the US in terms of his beliefs in democracy and liberty, sincerely sought to develop a close relationship with it. However, the Americans’ continued dependence on the UK, which they thought understood India better, regarding issues relating to security in the Subcontinent, significantly thwarted development of India-US relations on their own terms, says former Indian diplomat Shyam Saran.

By the 1950s, US dependence on the UK for engaging with India, its strategic relationship with Pakistan, and its all-encompassing preoccupation to contain communism had consolidated some old Indian suspicions and created a few others.

In fact, by this time, the friendliness with the Soviet Union and scepticism towards the US were not just the preoccupation of the elite, says Khurshid. “By the 1950s, it was quite clear that the US was not on India’s side even though it could not do anything to prevent India from achieving its objectives.”

“This was seen by all Indians,” he says. “The song of the time that resonated was Mera Joota hai Japani, Patloon Inglistani, Sar pe lal topi Rusi…the ‘lal topi Rusi’ was the critical thing…It was not the cowboy hat.”

The years of cordiality

From the beginning, India-US relations were seeped in ambiguity. No friendship or estrangement was total. By the late 50s, the US increased its foreign aid to India substantially, arguing that such an increase was in its interest, so as to not let communism spread in the subcontinent.

When a communist government came to power in Kerala through the majority vote, the Americans were particularly alarmed. If they did not give aid to the Nehru government, they would risk the breakup of India, and its orientation towards the communists, Eisenhower thought. Arms, economic assistance and diplomatic support—India received all from the US.

As argued by foreign affairs analyst Ashley J. Tellis in an essay in India’s Foreign Policy: “The US soon became during this period the largest donor to India and Washington viewed India as an important theatre in the struggle against global communism despite New Delhi’s reluctance to become formally allied with Washington in its anti-communist crusade.”

Yet, the fact that the US was still not willing to risk its relationship with Pakistan for India became clear when in 1960, Indian defence minister Krishna Menon asked the US if India could buy the Sidewinder missiles from them. Despite President Eisenhower’s initial willingness, the US finally decided against according the same benefits to India and Pakistan, given that the latter had taken “real responsibilities and risks” to be an ally.

After all, just a few months ago, the Pakistanis had provided the US facilities for sensitive intelligence operations near Peshawar.

Despite the Pakistanis, India-US relations during the difficult years of the Cold War reached their zenith in 1962, when the US strongly supported India politically, diplomatically and militarily during its war with China.

As argued by US diplomat Kux in Estranged Democracies, “India’s nonalignment seemed to be a thing of the past. In the face of India’s glaring military weakness, Nehru reversed policy 180 degrees to seek military assistance from the US, Great Britain and other Western countries.”

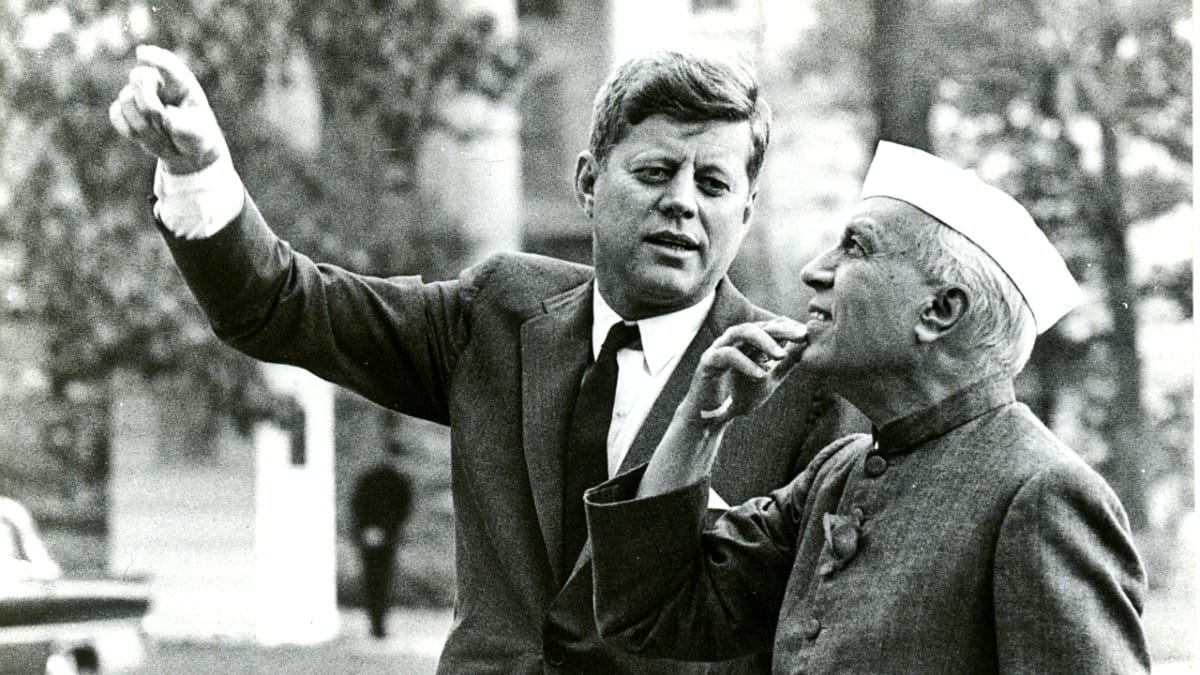

By November 1962, as panic reigned in Delhi, Nehru’s ask of the Americans became more surreptitious and desperate.

India feared the loss of Assam and possibly all of the North East. Without showing their copies to cabinet ministers or marking a copy to the Ministry of External Affairs, as was the convention, Nehru wrote two letters to then US President John F. Kennedy, asking for a dozen squadrons of US fighter aircraft, air defence radar, two squadrons of B-47 bombers, and asking American pilots to fly them till Indians could be trained to replace them.

The US Ambassador to India at the time, John Kennith Galbraith, suggested that the US Navy dispatch an aircraft carrier taskforce to the Bay of Bengal. But before the US could fully calibrate its response, the Chinese announced a ceasefire.

The Americans’ generosity was short-lived. The aircraft carrier they were going to send was USS Enterprise—the warship which the Nixon administration would send into the Bay of Bengal less than a decade later to pressure India during the war with Pakistan.

The spectre of the Enterprise would haunt the psyche of the Indian elite for decades.

Also Read: Trump’s MAGA politics is forcing Modi to change course of Indian diplomacy

The limits of cordiality

Less than three years after India’s humiliating defeat at the hands of the Chinese, serious clashes broke out on the Rann of Kutch after the Pakistanis began to send military patrols into the disputed area of the Kutch.

A brigade size battle between the Indian and Pakistani forces ensued. India admitted to having had 100 casualties. As Kux wrote, this was a fresh blow to Indian pride. “It was one thing to be pushed around by China, quite another to be bested by Pakistan.”

Part of the Indian ire was directed at the US. That the US would not allow its military aid to Pakistan to be used against India was the bedrock on which India-US relations, no matter how precarious, had hitherto stood. The 1965 war, was therefore, a blow.

Again, in a starkly similar hyphenation of India and Pakistan, which the Indians are protesting even now in the aftermath of Operation Sindoor, the Americans placed an arms embargo on both the rivalling nations.

“US assurances to India against the Pakistani misuse of arms had been the foundation of Indian defence policy,” then Indian ambassador B.K. Nehru wrote to US Secretary of State, Dean Rusk. “If these assurances are eroded, it would be a very serious matter … As far as India is concerned, the US response was inadequate.”

“When Kennedy and Nehru had met, Kennedy celebrated it as a meeting of two great democracies, which shared common values,” said Khurshid. “But those common values persuaded them to only take sides with India when it came to China, not when it came to Pakistan.”

The ‘ungracious’ aid

In the mid-60s, India seemed on the point of peril. For two consecutive years, the monsoons had failed. Risking a famine, India had to look to the US for wheat.

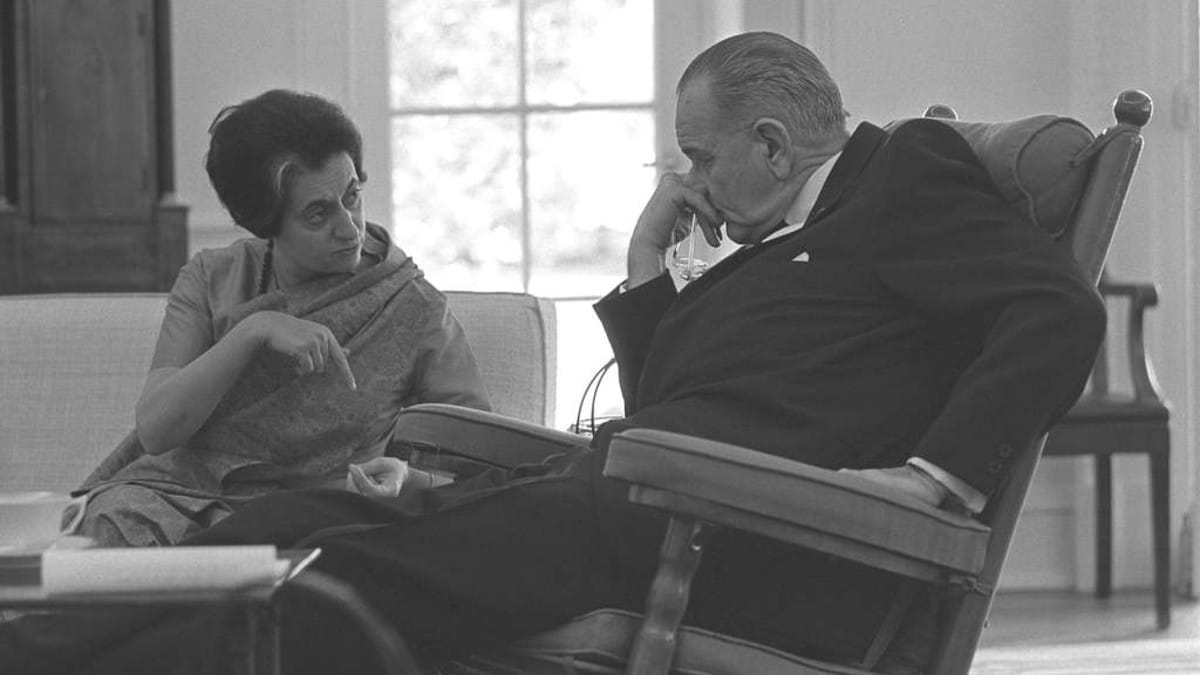

In 1966, when then PM Indira Gandhi met US President Lyndon B. Johnson, a newspaper from Alabama ran the headline: “New Indian Leader Comes Begging.”

The US administration’s response was only more diplomatically appropriate. Johnson refused to commit food aid under the nation’s Public Law 480, also termed the “Food for Peace” programme, if India did not agree to adopt the green revolution package.

Foreign aid was cut off. In a stark parallel with what is happening now, India, the US said, had to liberalise its trade restrictions before foreign aid could be made available again.

At one point, Indira phoned Johnson herself. Her press advisor, Sharada Prasad, who was present during the call, later recalled the Prime Minister being friendly and charming on the phone. But after she hung up, he remembered her angrily saying, “I don’t ever want us ever to have to beg for food again.”

The coercive American attempts to make India fall in line when it risked a famine prompted then agriculture minister C. Subramaniam to say “even a week’s failure in supply would create grave difficulties. That, from far off, people could not recognise. This is why I have said the United States always gives but not graciously”.

If Indian attitudes towards the US had been deeply soured by the twin blows of the Pakistan war and scars from the ungracious use of Public Law 480 as a diplomatic tool, India’s significance too had declined for the US, which once saw it as a powerful bulwark against communism. By now, as Kux wrote, “It (India) was just a big country full of poor people.”

That in this climate, the Indians would refuse to be party to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) was only a further irritant for the Americans.

Also Read: US bullying spurred Green Revolution. Let tariffs give us a Business Revolution

‘American duplicitousness’

By 1969, Richard Nixon, who had lesser patience for “Indian claims of moral leadership” than most of his predecessors, became the American president. A US government report on foreign policy published in 1971 stated with regard to South Asia: “we (the US) have no desire to press on them a closer relationship than their own interests lead them to desire.”

Clearly, the US wanted to distance itself from the region. Except, as the Bangladesh Liberation War broke out in March 1971, the opposite happened.

Even as public opinion in the US, and indeed within the government, turned against Pakistan’s atrocities in East Pakistan, Nixon sent angry messages, including one to his national security adviser, Henry Kissinger—“To all hands. Don’t squeeze (then Pakistan President) Yahya (Khan) at this time.” Arms to Pakistan flowed.

Those in the US establishment, including the US Consul General in Dhaka, Archer K. Blood, thought that given the US decision to keep away from matters of the subcontinent, and not humour Pakistan too much, the American should condemn the West Pakistanis for their blatant abuse of human rights. The US President was doing the opposite.

But few, not including the US secretary of state, knew what Nixon was covertly planning—his “most daring diplomatic manoeuvre yet”. Keen to now establish diplomatic relations with China as a counterbalance to the Soviets, Kissinger was to surreptitiously fly to Beijing—via Islamabad.

After visiting Delhi in July 1971, Kissinger left for Islamabad for a “routine visit”. On 15 July, Nixon announced that Kissinger had been to Beijing. A day later, Kissinger called L.K. Jha, then Indian ambassador to the US, to say “we would be unable to help you against China” if Beijing decided to militarily respond to a war between India and Pakistan.

Indians were infuriated. Not only was the US supplying weapons to the Pakistanis at a time when it was at war with India, but it was also using Delhi as a stepping stone for a secret trip to Beijing.

Weeks later in August, India signed the friendship treaty with the Soviets. With evident poetic hyperbole, Kissinger described the treaty in his memoirs as a “bombshell” and “as throwing a lighted match into a powder keg”.

Indira’s visit to Washington in November 1971 did little to improve the situation—it was a “dialogue of the deaf”. Nixon offered the Indian PM perfunctory sympathy for floods in Bihar. Indira chided him for ignoring human rights abuses in East Pakistan. The next day, Nixon made her wait at the White House for 45 minutes.

Military sales to India stopped. Even economic assistance froze. But the worst was yet to come.

On 10 December, 1971, as India and Pakistan officially broke out into war, Nixon directed the same aircraft carrier, USS Enterprise, which the Americans were considering sending for Indian aid during the war with China less than a decade ago, to the Bay of Bengal. As Kissinger put it many years later, “Its purpose was to give emphasis to our warnings about West Pakistan.”

While India won the war, and announced a ceasefire, for decades to come, the US carrier became “a symbol of American duplicitousness” for Indians. As Kux writes, sending the Enterprise never left the Indian psyche.

It became “tangible evidence” of the suspicion that Indians had always harboured, that the Americans sought to thwart Indian ambitions and aspirations. Pro-Soviet and anti-US voices in India had got their rhetorical ammunition for decades.

“This was the perfect example of an overbearing superpower taking India lightly,” former diplomat and Rajya Sabha MP Pavan Varma told ThePrint. “The US sending (a carrier from) the 7th Fleet in support of a Pakistani dictator against India was a scar for all Indians.”

Also Read: India can’t fight Trump tariffs with emotion. Smart talks, sector relief, reforms are key

End of Cold War & age of American aspiration

In an interview given to The New York Times in 1975, US Ambassador to India, William Saxbe sounded defeated. In the aftermath of the India-Pakistan war, Nixon had made several reconciliatory gestures, but to no avail. The most one could expect from India, Saxbe said, was “grudging respect”.

“If India is determined to make an enemy of the US, there is not a whole lot we can do about it,” he said. But he pointed to an important paradox of India-US relations.

“When I call on cabinet ministers, the President or Governors, they all love to talk about their sons, sons-in-law and daughters in the United States and how well they are doing and how well they are liking things,” he said. “The next day in the newspapers I read the same people denouncing the United States.”

By 1980, the number of Indians in the US was 3,00,000, writes Kux. Indian immigrants with high-tech degrees and fluency in English were the most successful ethnic group in the country. As cultural ties became closer and closer, diplomatic frostiness began to give way to reconciliation. Movies, literature, food and travel, increasingly everything that was aspirational was American.

By this time, Indira too wanted friendlier relations with the US. When the Americans began to heavily arm the Pakistanis in response to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, she did not attack them as vituperatively as she had in the 1970s. The fact that she was snubbed by the Soviets when she was out of power was no unimportant detail in this changing dynamic. Her foreign minister, Narasimha Rao, said this time around, Indira wanted to be more persuasive than rhetorical with the Americans.

Ronald Reagan, who came to power in 1981, “made a concerted effort to heal the breach between the two democracies”, writes Tellis. The 1982-91 period, thus, witnessed “delicately, gradually warming US-Indian relations”.

It helped that by 1984, a young, unpreachy and tech-savvy Rajiv Gandhi was in the seat of power in India. He was “unlike any preachy, arrogant, moralistic” Indian leader of the past. Most of his advisors were US-trained.

India-US relations were about to witness highs they had never experienced. As the Cold War came to an end in 1991, India and the US were in a way ready to establish a relationship on their own terms for the first time. As the Indian economy matured and opened up, it gave an added impetus to the US to invest diplomatically in this big emerging market.

The nuclear bind

The 1991-98 period, which witnessed an unprecedented strengthening of India-US relations, however, quickly ended with a bang—literally, writes Tellis. New Delhi was frustrated with the Bill Clinton administration’s “carve out” policy, which basically sought to segregate its disagreement with India on nuclear weapons, while strengthening bilateral ties in all other spheres.

Refusing to toe the line, New Delhi tested a series of nuclear weapons in 1998, and declared itself a “nuclear weapons state”, prompting an American meltdown.

Sanctions and admonitions followed. Even if they meant little in terms of India’s strategic programme, they “resuscitated past Indian memories of US opposition to India,” Tellis writes.

But as former Indian diplomat Saran explains, 1998 was a break and not a break point for India and the US.

Also Read: Trump’s Alaska summit was Putin’s victory. India is paying the price

The 123 Agreement

India-US relations since the time of Indian independence had suffered on account of three factors from the American perspective—India’s closeness to the Soviet Union, New Delhi’s economic underperformance, and Delhi’s status as a nuclear weapons state.

By the time George Bush came to power in the US, the first two factors had been eliminated by history. He decided to eliminate the third himself.

When Condoleezza Rice came to India in 2005 as Secretary of State, she “transformed the terms of debate completely by revealing that the Bush administration was willing to consider civilian nuclear energy cooperation with India,” wrote foreign policy expert Harsh V. Pant in his book The US-India Nuclear Pact.

“India’s relationship with the world had already been undergoing fundamental changes,” says Khurshid. “The USSR was gone, the rupee trade came to an end, and there was a feeling that India is missing out by not engaging with the US … All this came to a peak with the civil nuclear agreement.”

There were “old-time Soviet hands” like former diplomat and minister of external affairs, Natwar Singh, who were extremely ambiguous about how India could shift entirely from Russia to the US, Khurshid says. “But the ground reality had changed completely.”

“The nuclear deal changed perceptions of ordinary Indians, especially middle-class Indians towards the US completely,” he added. “I don’t think the US ever received the kind of empathy and support from India than it did in 2006.”

Estrangement as a natural state?

What does this long history of India-US relations tell us about the current moment? Has the long history of Indian suspicions of the US got a new lease of life? Or is this a transient moment? It depends on who one talks to.

“Scepticism or the absence of it are not genetic values,” says Varma. “All reactions are a product of the then prevailing set of circumstances.” While acknowledging the recent spate of events as “serious affronts” to India, he argues that this moment is a transient disruptor, one that cannot undo the dividends of the long-term Indo-American relationship.

However, sentimentality—“affront” would constitute as that—has no space in foreign policy and strategy, argues the prominent strategist quoted in the beginning.

“Indians have had a suspicion of Americans for decades, which stems more from a prickly nationalism than any grounding in reality… one would think that it had been eliminated after the 123 Agreement, but it is always lingering below the surface,” he says.

Adding, “It is that suspicion and hurt pride which sometimes does not allow India to respond practically to a crisis such as the present one, because the Indian position has always tended to stem more from an emotionality and post-colonial inferiority complex of the (Indian) elite than the practicalities of foreign policy.”

“We keep talking about the 1971 ship … the truth is India and the US have never fought a war, Americans have never killed an Indian, so where does this suspicion come from?” Varma asks.

Adding, “If you see the American position on the nuclear question as blackmail (the impression that the US always wanted India to abdicate its right to develop nuclear weapons), one cannot ignore that they changed the rules for you because they saw India as a special friend.”

Over the decades, the preponderance of the Left, India’s radical economic policies, the scientific community’s apprehensions because of the West’s implacability towards India’s nuclear programme, and the security establishment’s suspicions because of US’ ties with Pakistan, have all contributed to this deep Indian scepticism towards the US.

However, even in the absence of all these factors which have resolved themselves through these years, the suspicion remains, and that, the strategist argues, comes from the inferiority complex and love-hate relationship of the Indian elite with the US.

(Edited by Nida Fatima Siddiqui)

Also Read: Indian foreign policy is in free fall. Can we balance national pride with new power reality?

Good historical summary of Indo-US relations. However the conclusion seems to have been drawn in the 1980s and not in 2025. It’s not eg same elite. In fact India is now ruled by the counter-revolution Hindutva that shuns elitism as far as possible and tries to stick to ground realities as they evolve. PM Modi went as far as any PM would go in trying to deepen Indo-US friendship. Yet if things don’t seem to get better and Trump is contradicting things he himself did in his first term, this latest friction in ties should be read from the stark reality of an end-of-empire moment for America. Super debt is real, social fissures are real and the rise of Asia is a real threat. Within this, India is the world’s fastest growing economy among economies of all sizes. A daring new thesis and re-piecing the puzzle is required to draw any useful meaning out of this moment.