New Delhi: On the morning of 26 May, 1960, as skirmishes broke out along what we now call the Line of Control (LoC), India’s then Defence Minister V.K. Krishna Menon summoned a top-secret meeting in his office. General Kodandera Subayya Thimayya, the doughty Army chief — and an acerbic Menon critic — was present. So was the Chief of Air Staff, Air Marshal Subroto Mukerjee.

The instructions given to the military chiefs were clear — to find suitable sites for more air strips near posts on the Indian border. The strips would allow the new outposts India was setting up deep in the Himalayas, far from the nearest roads, to be supplied.

Five months later, on 20 October, 1960, Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru issued another set of instructions. Flying near the Sino-Indian border was now restricted. The Air Force was strictly not allowed to conduct sorties or reconnaissance missions within 24 km of the border. Only transport aircraft would be allowed to fly right up to the border.

In December 1961, Menon cleared an urgent request to waive this rule. An exemption was made allowing some specific flights — equipped with cameras — to map the terrain. These became reconnaissance missions for the Army in the Aksai Chin, Tawang, Sela, and Walong areas.

Then, in 1962, war broke out.

No strategic missions were carried out by the IAF, which stayed largely out of offensive operations. Instead, its brief was to only conduct transport and supply missions.

It is possibly the most famous “what if?” in modern Indian military history: Could the Indian Air Force have turned the tide to favour India during the Sino-Indian War of 1962?

The question, as it turns out, was being hotly debated during the war itself.

The Indian Air Force was not confident of success, according to the still-classified official record of the war, which ThePrint has accessed, written by the Ministry of Defence (MoD) in 1992.

The underlying assumption on the Indian side was that the Chinese had greater superiority in the skies. The only information available were sketchy snatches of intelligence, which, when combined with the difficult terrain and lack of infrastructure, painted a hopeless picture. It should be noted that while there was some aerial activity — albeit transport only — on the Indian side, there were no flights on the Chinese side.

According to the MoD’s official history of the war, aerial infrastructure was extremely weak at that time. There were no radars, the only radio link available in Leh had a range of barely 16 km, and only one sortie per day per aircraft was happening. On the eastern front, the jungle-covered terrain made close air support risky for an already-dispersed infantry.

Implementing the ‘Forward Policy’

Krishna Menon was reportedly in full favour of deploying the Air Force. The military establishment was more cautious: General Thimayya’s strategy was to bolster forces before even considering a forward advance. This changed when the ‘Forward Policy’ was adopted.

The Forward Policy — officially called so by the Indian military establishment — was the directive to establish forward posts to reclaim territory from China. The policy is seen as the immediate trigger to the 1962 conflict.

The political decision to implement the policy was taken during a top-secret meeting on 2 November, 1961. In attendance were Nehru — who chaired the meeting — Menon, Chief of General Staff Lieutenant General B.M. Kaul, Intelligence Bureau (IB) Director B.N. Mullik, and the new Chief of Army Staff Lieutenant General P.N. Thapar.

Notable opposition to the policy came from General Thimmayya, who had retired in May 1961. He had rejected the policy when Mullik first took the proposal to him, warning that the Indian Army should not go on the offensive until it was capable of being offensive. Nehru, on the other hand, endorsed the strategy of supporting bases on which troops could fall back on in the Lok Sabha in December.

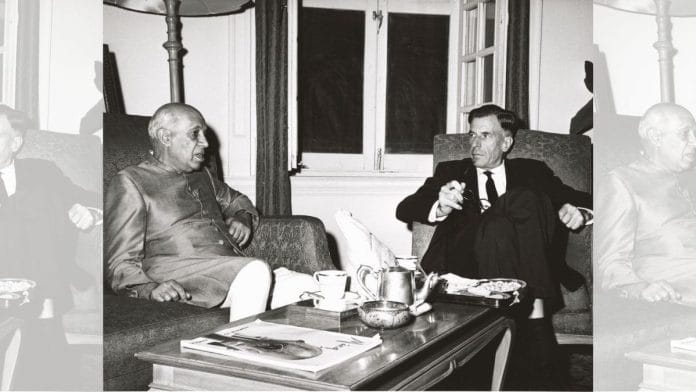

The Chinese view on the Forward Policy was that it was the Nehru government’s official step towards occupying Chinese territory and upsetting the status quo. It was also a signal that the 1960 talks between Nehru and Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai had failed to adequately address territorial concerns through diplomatic means.

Nehru was also being taken apart by the Opposition in Parliament. The situation was so tense — even physically so — on 5 December, 1961, that the Speaker had to interject several times to keep members of Parliament from losing their cool. “Why go on advertising unpreparedness?” demanded Bapu Nath Pai, a Bombay MP, criticising Nehru.

The policy broke the deadlock between India and China, but the question of deploying the IAF still remained up in the air.

Strong caution against air support

While the military were certainly hesitant, the strong caution against air support actually came from intelligence and diplomatic channels.

The three people who most influenced India’s decision not to deploy the Air Force were the director of the IB, the American ambassador to India, and a British advisor for defence.

IB Director Mullik wrote in his memoir that China’s bombers were capable enough to “penetrate as far South as Madras”, especially given the absence of night interceptors in India. He was the one collecting intelligence on Chinese capabilities.

The other player in the mix was the US Ambassador to India, Prof. J.K. Galbraith, who seemed to think that India should not deploy the Air Force during the war. The farthest that Indian planes would reach was Tibet, and there were no worthwhile targets there, according to Galbraith.

On the other hand, if the Chinese used their Air Force, the entire Gangetic plain and territory till at least Kolkata was at risk. It appears that India did request aerial support: Galbraith mentions a request made on 19 November 1962, in the thick of war, for US fighter planes to protect Indian cities. The request was not met.

Finally, a British military advisor, Prof. P.M.S Blackett offered his professional advice to Nehru — that the Air Force should only be used for tactical purposes because it would escalate the war.

And so, the decision not to use the Air Force was made. At the time, the Air HQ supported the move. Once the war was over, Chief of General Staff Kaul would confess in his 1967 memoir that India “made a great mistake in not employing our Air Force in a close support role during these operations”.

But by all records, the Air HQ had different assessments of the Chinese air threats at different times. “There is no accurate or authentic documentation of the thinking that was behind this decision to desist from use of offensive air support” reads the MoD’s official military history.

It was, it seems, just several mixed signals.

(Edited by Zinnia Ray Chaudhuri)

Also read: How Qing and British empires’ mapmakers laid the foundations for 1962 India-China War