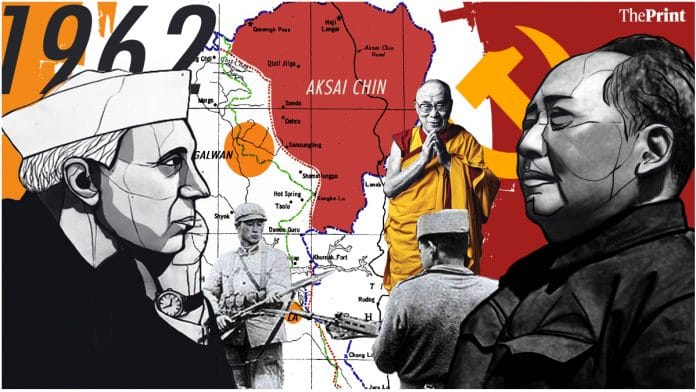

New Delhi: Sixty years ago, as the world nervously watched the US and the Soviet Union lock horns in the Cuban missile crisis, China and India went to war. While Indian academics, defence experts, and diplomats have picked apart where India went ‘wrong’, there is a dearth of material in the public domain on China’s motives behind the 1962 War.

As international affairs expert John W. Garver points out, little was published in China about why Chinese Premier Mao Zedong decided to go to war — unlike with the Korean War, the Indochina wars, and conflicts over the Offshore Islands in the 1950s, and the 1974 Paracel Island campaign. It can be argued that the same lack of clarity prevails today, with little consensus on Chinese intentions that culminated in the 2020 Galwan clash.

That said, it appears that apart from questions over Tibet’s autonomy, the Chinese leadership was guided to some extent by perceptions of then Indian prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru. According to Garver, Nehru was viewed — through the lens of communism — as a member of the Indian bourgeoisie who sought to create a “great Indian empire” and fill the vacuum left by the British.

By 1959, Beijing had some concerns about the international fallout of its tensions with India, mainly whether it would invite American involvement, how Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev would view China’s actions during the conflict and in turn, how all of these factors may affect China’s standing in the global communist movement.

The Chinese policy, however, was based on contradictory assumptions by 1961, note the CIA’s declassified POLO archives. While the Chinese felt it was necessary to “unite” with Nehru as India was seen straddling ‘socialist’ and ‘imperialist’ camps, they also believed that a fight with the neighbouring country would go a long way in proving China’s strength.

There also appeared to be a sense of wanting to teach India ‘a lesson’, experts have noted.

Also Read: From clash at Longju to ‘Operation Leghorn’, how skirmishes built up to 1962 India-China war

Perceptions of Nehru as ‘expansionist’

Chinese perceptions of Nehru played a major role in Beijing’s justifications for its actions between 1959 and 1962.

According to the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), prior to the Tibetan revolt in March 1959, there was a sense among Chinese leaders that Nehru was more conciliatory toward them than the Indian opposition, the press, and even some members of his cabinet.

But after the Tibetan revolt, when “anti-China” chorus grew loud in India, it was felt that Nehru may have encouraged it. This also led to perceptions that Nehru was a “two-faced” neutral — who professed neutralism but was actually anti-Chinese on key issues.

The Dalai Lama’s statement at Tezpur on 18 April 1959, in which he said he had left Lhasa because Tibet did not have any autonomy under the Chinese Communists, further complicated matters.

Nehru’s speech in Parliament on 27 April 1959 sought to clear things up. “I should like to make it clear that the Dalai Lama was entirely responsible for this statement… Our officers had nothing to do with the drafting or preparation of these statements,” he said.

But that did little to change Chinese perceptions. If anything, the speech made Nehru seem more sympathetic to the calls for “real Tibetan autonomy”, notes the CIA archive.

About a month later, the Chinese state-run newspaper People’s Daily called on the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the public to “study” Nehru’s speech after which the Chinese sharpened their criticism of the Indian prime minister, the CIA archive adds.

Further, Mao saw Nehru as a member of the Indian bourgeoisie who had inherited British “expansionist” strategies and sought to turn Tibet into a “buffer zone”, so that it may later become a protectorate or colony of India.

“Creation of such a buffer zone had been the objective of British imperial strategy, and Nehru was a ‘complete successor’ to Britain in this regard. Nehru’s objective was the creation of a ‘great Indian empire’ in South Asia by ‘filling the vacuum’ left by a British exit from that region,” observes Garver.

This was, however, a deep misperception, he adds.

The arguably accurate perception that Nehru preferred negotiations and was unwilling to go to war also guided some military actions such as Beijing’s conscious ambivalence about the wide gap between Chinese and Indian claims on maps.

According to the CIA, the Chinese were deliberately deceptive about maps, felt the Line of Actual Control (LAC) need not be delimited, the matter could remain in “limbo” and that there was no need to alert Nehru about it. “The Chinese acted to establish in writing a definitive border position with the apparent goal of compelling Nehru to accept it. They probably estimated that his consistently conciliatory responses to their military action reflected his unwillingness to risk armed conflict,” notes the CIA.

Teaching India a lesson

What also influenced China during the war, was the need to make India acknowledge the power of ‘New China’. This referred to the newly minted People’s Republic of China (PRC), which was formed under the Chinese Communist Party barely 13 years prior to the 1962 war and was still vying for admission into the United Nations (UN).

Therefore, there was a sense of wanting to prove China’s strength. This is evident in Chinese thinking about how to respond to India’s Forward Policy.

“The final Chinese decision to inflict a big and painful defeat on Indian forces derived substantially from a sense that only such a blow would cause India to begin taking Chinese power seriously,” notes Graver.

The 25-26 August 1959 skirmishes also hurt Chinese national sentiments as Beijing believed India was helping Tibetan rebels re-enter Tibet, especially in Migyitun area.

The gap between India and China’s perceptions of one another, and how each figured into another’s foreign policy was evident in a January 1961 report from the Chinese foreign ministry.

The report noted that China saw the US as its major world enemy, followed by India and Indonesia somewhere lower on that list. However, as pointed out by the CIA, India wasn’t privy to this hierarchy and to the Indians, even the smallest degree of Chinese animosity could elicit provocation.

(Edited by Amrtansh Arora)

Also Read: How Qing and British empires’ mapmakers laid the foundations for 1962 India-China War