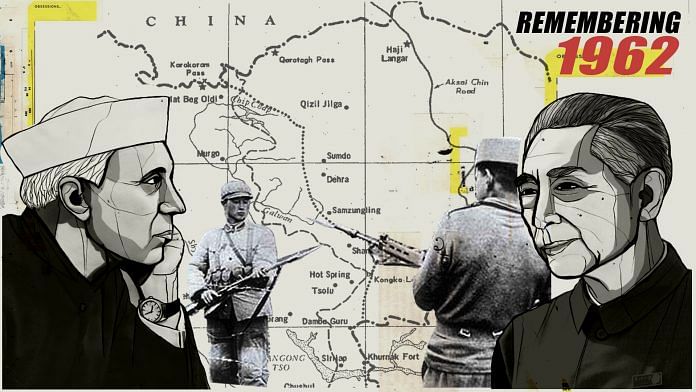

New Delhi: In 1959, three years before the Sino-Indian War, personnel from India’s Assam Rifles clashed with Chinese troops at Longju in the Tsari Chu valley, now controlled by China.

Scholar Srinath Raghavan argues in his book War and Peace in Modern India that it was only after this encounter that India and then prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru started to take the chances of war with China seriously. Specifically, only after the Longju skirmish was the Army given control of the “frontier areas”.

The path to the Sino-Indian war of 1962 was littered with skirmishes and patrol clashes in the preceding years and months— from Longju in 1959 to the Dhola Post in September 1962.

These encounters were a forewarning that preceded the perilous Chinese onslaught across the western and eastern sectors of the Line of Actual Control (LAC) on 20 October that year.

Also Read: A face-off in Galwan, 60 years ago: How border brinkmanship triggered 1962 India-China war

Forward Policy & Dhola Post

After Longju, another skirmish took place near the Thagla ridge, right on the cusp of the conflict.

As part of the ill-fated Forward Policy, Indian forces had set up a patrolling post at Dhola by 4 June, 1962. Dhola was situated near the erstwhile North-East Frontier Agency (NEFA)—Bhutan—Tibet trijunction, directly below Thagla ridge.

Explaining India’s rationale for claiming the Thagla ridge, Raghavan explains, “According to the treaty map of 1914, the McMahon Line ran south of the Thagla ridge. Indians held that if the boundary was supposed to follow the watershed, and if the Thagla ridge had not been explored at that time, then the line lay on the Thagla ridge despite its erroneous depiction on the map.”

As the Official Indian War History published by the Ministry of Defence (MoD) in 1992-93 recounts, the Indian post at Dhola was encircled by the Chinese on 8 September. An abridged version of the Henderson Brooks Report, published by Australian journalist Neville Maxwell in 2014, reported that 800 Chinese soldiers had encircled the Dhola Post after having occupied the Thagla ridge above between August and September 1962.

Then, between 10 and 11 September, India — at a meeting chaired by then defence minister Krishna Menon — decided to expel the Chinese from the ridge, if necessary by force, the war history adds.

The ministerial decision trickled down the chain of command. General P.N. Thapar, then Army chief, relayed the decision to the Eastern Command, which informed the XXXIII Corps, and finally, the 4th Infantry Division was told to “carry out the decision”.

The operation to evict the Chinese from Thagla ridge was code-named “Operation Leghorn”.

As the Indian military was coordinating its plan to offset the Chinese, around 11 pm on 20 September, Chinese troops hurled hand grenades into one of the Indian bunkers at the Dhola Post, wounding three Indian soldiers. The incident triggered hostilities, with Indians and Chinese exchanging fire intermittently till 29 September, 1962.

Operation Leghorn

According to the action plan prepared by Brigadier John Dalvi, commander of the 7 Infantry Brigade, Indian forces were to launch “Operation Leghorn” on 10 October.

On D-Day, personnel of 2 Rajput Regiment were making their way up the southern bank of the river Namka Chu, towards Yumtso La — a mountain pass west of the Thagla Ridge on the LAC — when they came under fire from a Chinese battalion. Consequently, soldiers of 9 Punjab, posted ahead at Tseng-Jong, were attacked by Chinese mortar shelling.

“No sooner was the fire lifted, and at 0800 hours, approximately 800 Chinese attacked [again] the Punjabis at Tseng-Jong from the East and North-East. After a heavy exchange of fire for about 45 minutes, the attack was repulsed,” the war history adds.

The Chinese then continued attacking 9 Punjab from the north, east, and west with 88mm mortars, grenades, and automatic weapons.

India lost six jawans in those attacks, while 11 were wounded and five were reported missing. Given the continuous onslaught and untenable situation, a withdrawal was ordered and the Chinese occupied Tseng-Jong.

However, this wasn’t the last of the skirmishes that served as a prelude to the Chinese blitz across the Namka Chu on 20 October, 1962.

On the intervening night of 15 and 16 October, China began to probe Indian positions at Tsangle before opening fire at them the next day. Over the next two days, the Chinese repeatedly hurled grenades at Indian troops at Tsangle.

On 19 October, a day before the outbreak of war, an Indian patrol clashed with the Chinese. Consequently, the war history notes, “By 19 October, there were unmistakable signs that an attack was imminent.”

(Edited by Amrtansh Arora)

Also Read: ‘Nobody crosses over now’— what Indo-Tibetan tribes that helped Army in 1962 China war lost